by David B. Williams Monday, June 20, 2016

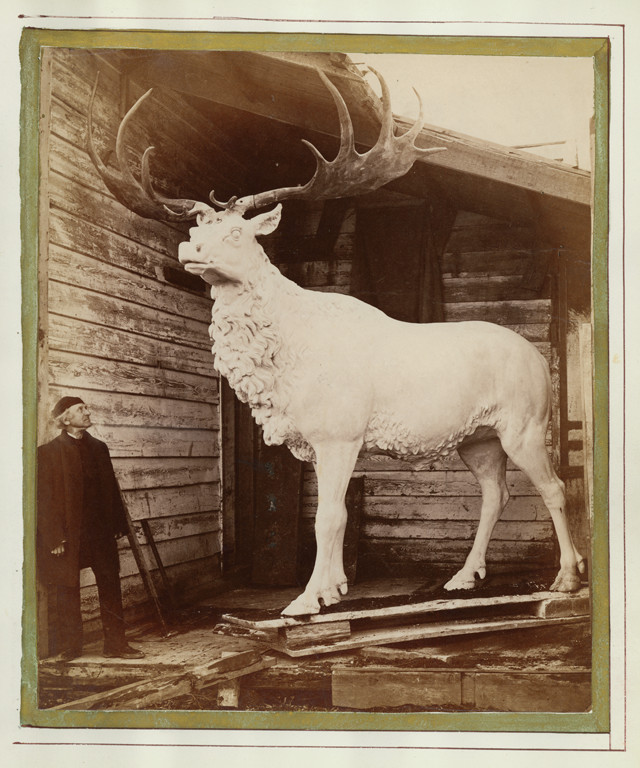

Hawkins with his statue of the Irish elk, Megaloceros, circa 1853. Credit: Academy of Natural Sciences, Ewell Sale Stewart Library and the Albert M. Greenfi eld Digital Imaging Center for Collections.

Surprisingly, there is precedence for eating dinner in the body of a massive beast. In February 1802, Rembrandt Peale, an early American painter best known for his portraits of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, invited 12 friends and family to dine under the rib cage of a mammoth, which had recently been erected in his father’s museum in Philadelphia.

The bones of what were called the American incognitum had come from the Hudson River Valley, a few kilometers west of the town of Newburgh. First discovered in1790, the mammoth fossils had attracted the attention of Thomas Jefferson, who, despite the controversy over his presidential election in 1800, took the time to inquire about buying the specimens. He was unsuccessful, but in 1801, artist and museum owner Charles Willson Peale bought the bones for $200, plus $100 for any new ones he could dig up. He eventually collected enough bones from a variety of bogs and marl pits to assemble two nearly complete mammoth skeletons. (The remains were later identified as mastodons.)

Rembrandt, Charles’ son, staged his dinner to celebrate his upcoming trip to Europe, where he would display one of the family’s mammoths. Thirteen men, including Rembrandt’s siblings Rubens and Raphaelle, sculptor William Rush, botanist William Darlington and inventor John I. Hawkins, sat at a round walnut table beneath the bones. As would happen almost 52 years later, much frivolity ensued followed by solemn toasts such as “All Honest Men — If they cannot feast in the Breast of a Mammoth, may their own breast be large enough … Success to these boney parts in Europe,” as described in The Port Folio, a Federalist, anti-Jefferson journal, on Feb. 20, 1802.

In the same issue, Samuel Ewing, a Philadelphia lawyer, lampooned the dinner with lines such as “What toasts roar’d loudly thro’ the Mammoth’s ear, or, Were sweetly sounded thro’ his wide posterior.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.