by Erin Wayman Thursday, January 5, 2012

Natural Resources Conservation Service employees conduct a snow survey near Mount Hood in Oregon. Photo by Ron Nichols, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

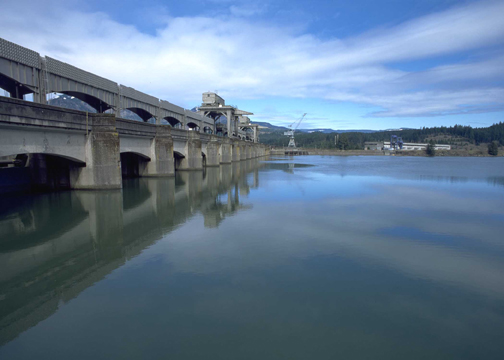

The Bonneville Dam sits on the Columbia River between Oregon and Washington. Changes in snowpack could affect hydropower generation throughout the Pacific Northwest. Photo by Ron Nichols, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

Portland receives much of its water from the Bull Run River Watershed, near Mount Hood. Cacophony, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

If you turn the tap on in Seattle, the water flowing from the faucet likely originated as a clump of snow. In winter, snowflakes fall in the Cascades, accumulating in thick snowpack. The snowpack stores water in winter and slowly releases it in spring and summer as temperatures warm and snow melts. As snowmelt flows down the mountains, some of it is diverted and collected in reservoirs — destined to arrive in the homes of more than 1 million people.

Water supplies used for drinking, agriculture and hydroelectricity make similar journeys all across the West Coast. From Seattle to Los Angeles, anywhere from 50 to 80 percent of the water people use comes from mountain snow. It’s a clean, reliable source of water. But it may soon become less dependable.

Climate change threatens to disrupt the balance of water and snow in the mountains, by altering mountain snowpacks in several ways. First, warmer winters may cause snow to melt earlier in the year or cause precipitation to fall as rain rather than snow. Both scenarios would make less water available in the drier spring and summer months when water demand is highest. In addition, faster releases of water down mountains could lead to more flooding; that rush of water would be more difficult to manage and collect than gradually melting snow. On the other hand, climate change could result in less or more variable precipitation, decreasing the water supply. Models suggest all are possible, depending on the location. Water managers and utilities are not waiting around to see what happens. They are teaming up with climate scientists to assess how their local water situation may change in the future and to consider how to adapt to such changes. Given the uncertainty that surrounds climate models and forecasts, it’s not an easy task.

To make decisions about water supplies, water managers need to know how much snowpack is present in their systems. The first snow surveys in the American West began in the early 1900s, when researchers climbed mountaintops and manually measured snow depth. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) started recording such data in the 1930s, and continues to manually collect snow data at 1,200 sites run by the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). In addition, since 1980, NRCS has gathered data with automated SNOTEL (SNOwpack TELemetry) sites, which record snow depth, snow water content, temperature, precipitation and other climate data. Today, there are more than 750 SNOTEL stations. With all of these data, NRCS creates forecasts of streamflow throughout the American West.

Because snow records go back to the early 20th century, scientists can study the records to see how snowpack levels have changed over time. Many studies have found evidence that snowpack is decreasing, snow is melting earlier, and more precipitation is falling as rain. These effects are most pronounced in coastal ranges, such as the Cascades of western Washington, western Oregon and northern California, where snowpack often exists near the freezing level. Even modest amounts of warming in these areas can make a big difference.

In the Cascades, scientists have reported anywhere from a 20 to 40 percent decline in snowpack over the second half of the 20th century. Various studies have also reported that the mountain range could lose anywhere from 11 to 18 percent of spring snowpack for every degree Celsius of warming it experiences.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.