by Piper Lewis Tuesday, June 30, 2015

Sailing the waters of the Arctic or Antarctic requires icebreakers — ships built to withstand polar conditions and break through sea ice. Credit: U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer Prentice Danner.

The sun doesn't set in the Arctic summer. Credit: Piper Lewis.

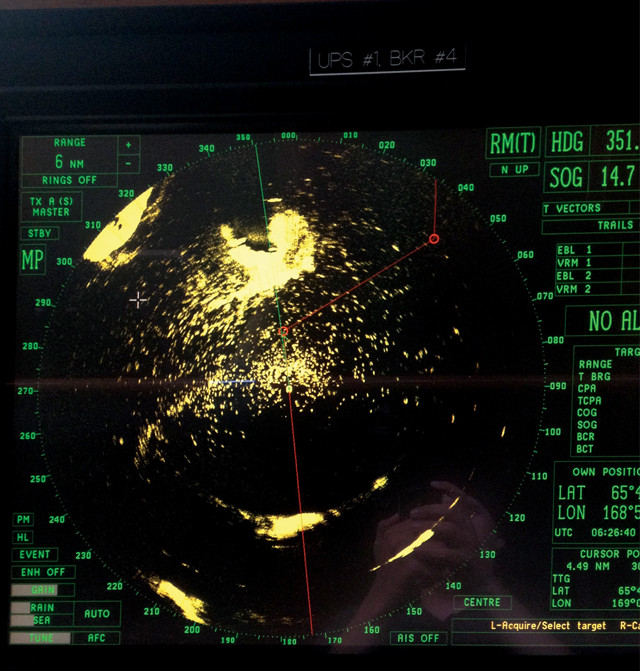

The shipboard radar of the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy shows a confused mass of yellow, the radar reflections of thousands of birds. Credit: Piper Lewis.

I had never seen so many birds in my life. The sunset turns the world a deep pink as auklets and murres spiral up to their nests on the Diomede Islands, two rocky outposts in the Bering Strait equidistant from the shores of Alaska and Siberia. The seabird observers count as quickly as they can; the shipboard radar of the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy shows a confused mass of yellow at our location — the radar reflections of thousands of birds. Meanwhile, scientists in a lab on the Healy take samples of water collected at different depths below us from a rosette of Niskin bottles, while others on the aft deck collect plankton with giant ring nets. This is life aboard a research icebreaker in the Arctic.

In 2013, I had the pleasure of working as a research assistant intern aboard the Healy, one of the United States’ two publicly owned icebreakers. Working above the Arctic Circle on an icebreaker is a unique and exciting adventure. I was there in the dead of summer, bathed in near-constant daylight once we passed through the Bering Strait into the Chukchi Sea, and surrounded by strange, surreal vistas of sea ice. But whatever time of year one visits the Arctic, there is magic to be found. Sailing the waters of the Arctic or Antarctic requires icebreakers — ships built to withstand polar conditions and break through sea ice. But the U.S. fleet unfortunately faces challenges in continuing to support these efforts. Given the age and condition of its existing ships, the Coast Guard will not be able to meet U.S. needs by 2020 if the federal government does not procure new icebreakers.

The R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer, a research vessel with icebreaking capability, is leased by the National Science Foundation for use by the U.S. Antarctic Program. Credit: ©Eli Duke, CC BY-SA 2.0.

The U.S. icebreaker fleet consists of two government-owned ships: the Healy and the Polar Star. The Healy is primarily a scientific research vessel, although it can also conduct search-and-rescue operations, escort ships, and provide environmental protection and law enforcement. It is a medium-grade icebreaker, which means it can break ice that’s up to 1.4 meters thick while traveling at 3 knots and can break ice up to 2.4 meters thick via ramming. It can operate in temperatures as low as minus 46 degrees Celsius. The Healy was built in 1999 and began service in 2000. It has almost 400 square meters of space available for onboard labs and berths for 50 scientists (in addition to the crew).

The Polar Star is the only functional heavy-grade icebreaker in the U.S. fleet. Entering service in 1976, the Polar Star served its initial 30-year lifespan, and then was refurbished and reactivated in 2012 after its sister ship, the Polar Sea, suffered an unexpected engine failure that put it out of service in 2010. The Polar Star is able to break 2 meters of ice at 3 knots and can break ice up to 6.4 meters thick by ramming. It provides berths for 20 scientists (along with a Coast Guard crew of about 140) and has five laboratories. It will be stationed primarily in the Antarctic for the next five years.

Two other icebreakers operate out of the U.S. The R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer is a research vessel with icebreaking capability that is privately owned by Edison Chouest Offshore and leased by the National Science Foundation for use by the U.S. Antarctic Program. It entered service in 1992 and can break through 1-meter-thick ice at 3 knots, but it has no ice-ramming capability. Lastly, Royal Dutch Shell PLC leases and operates the icebreaker Aiviq, also owned by Edison Chouest, which supports oil exploration and drilling.

The problem with the U.S. icebreaking fleet today is that it’s far under capacity to meet the demand of national interests, and the ships it does have are already well into their expected lifetimes. Beyond the expected service life, icebreakers require extensive maintenance and costly repairs and modernization to remain operational, according to the Coast Guard. The Healy is already 15 years old, halfway through its projected lifespan, and the Polar Star has already been refurbished once so it can continue to serve for an additional seven to 10 more years.

Beyond their importance in facilitating scientific research, there are nowhere near enough icebreakers to fulfill the most recent Naval Operations Concept (NOC), issued in 2010. The NOC, a unified vision of the missions of the Coast Guard, Navy and Marine Corps, says that icebreakers are necessary to assert U.S. policy in the Polar Regions. They “are the only means of providing assured surface access in support of Arctic maritime security and sea control missions,” according to the NOC. The global missions of the NOC require “continuous icebreaker presence in both Polar Regions” according to a Congressional Research Service (CRS) document on polar icebreaker modernization, which says the Coast Guard will need three medium and three heavy icebreakers to fulfill the NOC. The national fleet will need an additional three icebreakers, according to CRS, for a total of 10 ships — four medium and six heavy — to fulfill its statutory missions as well as the more stringent national security requirement to “maintain continuous presence” in the Arctic.

Scientists sampling the ocean and sea ice as part of the ICESCAPE program. Credit: NASA/Kathryn Hansen.

Primarily working as a research vessel, the Healy provides scientists the opportunity to gain insight into the biological diversity of the Arctic Ocean floor, make detailed analyses of ocean chemistry, and observe birds and megafauna in their natural environments.

Icebreakers allow up-close analyses of the Arctic Ocean and on-location lab work, says Lee Cooper, an oceanographer at the University of Maryland’s Center for Environmental Science who has spent time aboard the Healy. “Many of the Arctic systems we work in are not accessible without ice-capable vessels,” Cooper says. Ice is still present year-round in many parts of the Arctic, he notes. “Some of the more interesting and productive times to visit the Arctic are when the ice is melting in the spring and the plankton are blooming, but this is not a time you can sail anywhere you want without taking into account the type of ship you are on and whether it can penetrate ice.” Cooper’s research focuses on the distribution and cycling of nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, needed by marine organisms in the Arctic environment, as well as how these processes are affected by changes in ecosystems, such as those observed as a result of seasonal sea-ice retreat.

Cooper and other researchers, including his collaborator and spouse Jacqueline Grebmeier, a biological oceanographer also at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, have worked aboard the Healy to study the changing seasonality of biological production as sea ice retreats earlier in the summer. Grebmeier is investigating the impact of ocean acidification in the Arctic on benthic organisms like clams and crabs. Increased seasonal thawing of ice allows the ocean to acidify to lower depths, and these impacts have started to ripple up the Arctic food chain, she noted in a presentation at the Consortium for Ocean Leadership Arctic Science Forum — a public policy forum focusing on predicting and preparing for the changing Arctic, held in Washington, D.C., in March 2015.

At the forum, Grebmeier explained how decreased sea-ice extent makes it difficult for higher-trophic-level mammals such as walruses to thrive as well. The critical efforts to understand these changes are conducted using many scientific tools, including gliders, moored buoys, satellites and ships like icebreakers, she noted.

Other researchers have been studying the region with an eye toward future natural resource development. If the Arctic is to host more oil and gas exploration, it will be important to set environmental baselines, said Samantha Joye, a marine scientist at the University of Georgia who testified in a recent congressional hearing on the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Without prior benchmarks, she noted, it is hard to determine the impact of an oil spill in the aftermath of an event like the Deepwater Horizon blowout. Arctic research allows scientists to establish those baselines and helps the government make informed decisions about natural resource development.

One of several science labs on the Healy. Credit: Piper Lewis.

The research in which I participated on the Healy focused on Hanna Shoal in the Chukchi Sea north of Alaska, an area of intense biodiversity and a critically important walrus feeding ground. In part, this research helped inform the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s (BOEM) new 2017–2022 Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program.

But icebreakers’ importance goes far beyond research and natural resources applications: They are needed for everything from national security to transportation and even tourism. Not only do these vessels maintain shipping lanes through icy waters, they provide the Coast Guard and Navy with the necessary support to ensure security and law enforcement, and to conduct search-and-rescue missions, as needed in the Arctic.

Coast Guard crew aboard the Healy deploy a meteorological buoy in the Arctic Ocean. Credit: NASA/Kathryn Hansen.

Scientists stand in a melt pond on the ice in the Chukchi Sea, drilling holes for instruments to be deployed to sample the physical, chemical and biological characteristics of the ocean and sea ice as part of NASA's ICESCAPE mission aboard the Healy. Credit: NASA/Kathryn Hansen.

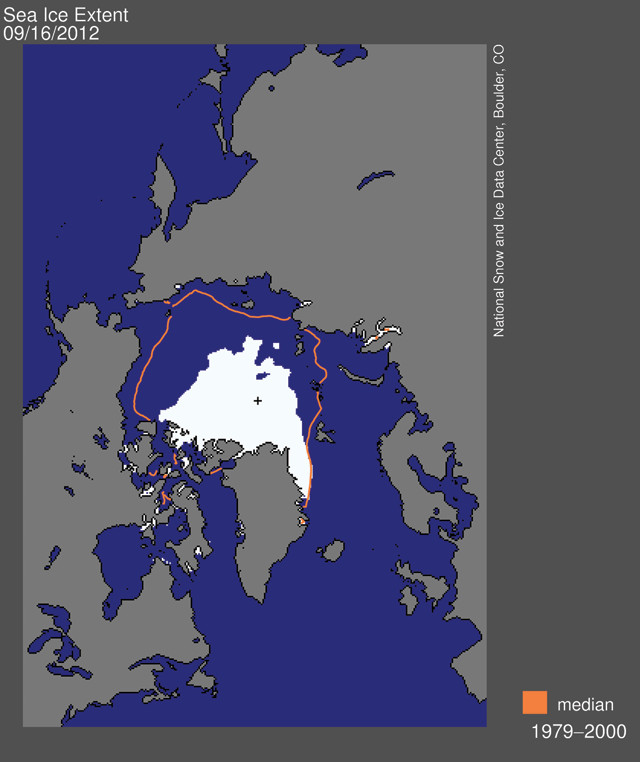

The Arctic is one of the fastest-changing places on Earth. It has seen a particularly dramatic change in sea ice over the last 35 years, with the annual minimum extent dropping by an average of 12 percent per decade since the late 1970s, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo. Between 1975 and 2012, sea-ice thickness has decreased 65 percent as well. Sea-ice reduction allows for increased wave action, which in turn leads to increased coastal erosion. Less sea ice also increases global temperatures, as more solar heat is absorbed into the dark ocean instead of reflected off light-colored ice.

As the ice has melted, previously nonexistent travel lanes have opened in the summer, which has led to increased traffic in the Arctic — including tourist traffic, which is expected to rise with further ice retreat — along with maritime shipping, scientific research, and oil and gas development. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that 70 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and more than 70 percent of undiscovered natural gas is in the Arctic. BOEM estimates that 27 billion barrels of oil and 131 trillion cubic feet of natural gas exist on the U.S. Arctic outer continental shelf. In May 2015, President Obama conditionally approved plans for Royal Dutch Shell PLC to drill on the outer continental shelf of the U.S. Arctic. As the U.S. moves forward with such development, the need for icebreaker support in the Arctic becomes more pressing.

Furthermore, there are issues of national security in the Arctic. In the National Strategy for the Arctic Region released by the White House in 2013, the Obama Administration lists advancing U.S. security interests in the Arctic as one of its primary focuses. The document highlights the need for “vessels and aircraft to operate, consistent with international law, through, under and over the airspace and waters of the Arctic” to support lawful and safe commerce, scientific operations and national defense.

Coast Guard Commandant Adm. Robert Papp has testified in front of Congress multiple times on the need for higher funding levels for icebreakers and other projects. Credit: U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 2nd Class Patrick Kelley.

On Sept. 16, 2012, Arctic sea ice reached its lowest extent since satellite records have been kept. Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center.

The Coast Guard has been pleading its case for more funding for icebreakers for years now. In 2011, Coast Guard Commandant Adm. Robert Papp told Congress that there “are no icebreakers available … for leasing right now, they would have to be constructed.” But that’s no small undertaking, with the Coast Guard estimating that new icebreakers will cost between $900 million and $1.1 billion. The Coast Guard would need $2.5 billion a year, Papp said, to sustain its capital plan for Acquisition, Construction and Improvements (AC&I) at a level that could support all Coast Guard ships and aircraft, including icebreakers. The AC&I is the Coast Guard account that provides funding for infrastructure such as patrol boats, helicopters, and vessel sustainment, as well as computers, intelligence and surveillance equipment, and navigational aids.

In 2013, Adm. Papp again testified before Congress, stating that the $1 billion funding level proposed in the Coast Guard’s fiscal year (FY) 2014 budget for overall AC&I and capital investment would allow the Coast Guard to meet its highest priorities but that it would require the termination or reduction of other projects, such as acquiring new icebreakers. Deferring purchases of new ships, including icebreakers, Adm. Papp explained, might create a “death spiral” as the Coast Guard is forced to sustain older, costly assets while unable to purchase replacements. Testifying again in 2014, he said that finding $1 billion in the 2014 budget for an icebreaker would displace other higher priorities, such as the procurement of other necessary vessels.

According to a report by the Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General, if the U.S. government does not procure new icebreakers, the U.S. will be without icebreaking capacity beyond 2029. However, even stopgap measures, such as reviving the Polar Sea — which would cost about $100 million, according to Vice Adm. Peter Neffenger, Vice Commandant of the Coast Guard, who testified before Congress in 2014 — are not in the budget.

The president’s proposed FY16 budget, released in February 2015, included only $4 million toward the $1 billion needed for icebreaker procurement. In March, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) proposed an amendment to the Senate’s congressional FY16 budget that supported increasing the U.S. icebreaker fleet. The Senate unanimously agreed to the amendment. Although the amendment shows Senate support for building icebreakers — and both Congress and the Obama Administration are in favor of building the new fleet — the funding is still lower than what’s necessary, according to Coast Guard Adm. Paul Zukunft, Papp’s successor, who testified to Congress in March 2015. “We are treading water now,” but with any further reductions, the Coast Guard will be “taking on water,” Zukunft said, adding that “there is no money for me to address the Arctic.”

The Healy rescues a Russian tanker stuck in ice near Nome, Alaska, in January 2012. Icebreakers are necessary for such rescues and will become increasingly important as the polar regions open to more maritime traffic. Credit: U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 1st Class Sara Francis.

There’s little money from other sources either it would seem. At the Arctic Forum, National Science Foundation (NSF) Director France Córdova spoke about her agency’s financial support for scientific research. NSF spends $100 million on Arctic science, $40 million of which goes to logistics and $60 million to research and field support. This money is used for permanent research sites, helicopters, boats, land observations and leasing space on icebreakers, but NSF does not have a high enough funding level to assist with icebreaker construction.

Despite the difficulties of getting funding for new icebreakers, it is clear to many that a pathway to procuring new icebreakers is necessary for the U.S. to maintain its Arctic presence. On May 19, 2015, Senators Murkowski and Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) introduced the Icebreaker Recapitalization Act. “Our legislation makes sure that the United States is able to protect our interests in the Arctic, and it gives the men and women in the Coast Guard and Navy the tools they need to do their jobs,” Cantwell said about the bill. The bill would authorize six icebreakers designed by the Coast Guard to be constructed by the Navy. (By a similar arrangement, the Navy’s shipbuilding account paid for and constructed the Healy in 1990.) Sen. Murkowski emphasized the important role icebreakers play for the U.S.: “From a military perspective, this is an imperative; from an economic development viewpoint, it is a down payment on an Arctic future; and as a scientific research opportunity, it opens up a new world of knowledge.” Whether anything will come of the new bill remains to be seen.

Without icebreakers, researchers could not do research during some of the most biologically productive times in the Arctic. No icebreakers means studies like the one I participated in on Hanna Shoal could not be conducted, which would limit availability of scientifically important data necessary for accurate environmental assessments in resource development planning. Icebreakers also allow for Antarctic resupply, and without icebreakers, McMurdo Station — the main U.S. station in Antarctica — could not operate as it does today. A lack of icebreakers means no rescue for fishermen, tourists or scientists stranded in heavy ice. Icebreakers are intrinsic to commerce, security and the future of polar science.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.