by John C. Mutter Thursday, April 20, 2017

In February 2017, the spillway for the Oroville Dam — the nation's highest dam — started to crumble, threatening about 200,000 people downstream, including people in Oroville, Calif., who were required to evacuate. The spray cloud from the spillway can be seen in the distance, as can the earthen dam to the right of the spillway. Credit: Kelly M. Grow/ California Department of Water Resources.

Natural disasters are viewed as moments, sometimes agonizingly drawn out, when Earth undergoes paroxysms in populated areas that result in fatalities and economic losses. As physical scientists who study natural disasters, geoscientists typically look at the problem from the front end: Our focus is mostly on prediction, forecasting and prevention. We don’t often weigh in on the long-term societal implications of whatever natural disaster we’re studying. But perhaps we should, or at the very least be conversant with how a social scientist, like an economist, might think about disasters. A more holistic view might help us do more good than studying the physical science of disasters alone.

More than 100,000 people in New Orleans had no access to a car so they could evacuate when the city was flooded by Hurricane Katrina. Credit: NOAA.

From an economist’s perspective, deaths are a loss of human capital. But those most at risk in natural disasters are the very young and the very old, who do not make large contributions to modern economies. Thus, the reasons to prevent death are not economic, but humanitarian, and that should surely be enough.

To prevent deaths, it helps to know who is being killed. However, accurate statistics on deaths and injuries during natural disasters are often hard to find: Poor countries overstate fatalities in hopes of attracting aid (it works); rich countries downplay fatalities out of embarrassment and suggest the lack of adequate preparation or response as explanations. There’s only one virtual certainty when it comes to disaster death tolls: Being old or being poor exacerbates your risk. Disasters throughout history have taken disproportionate tolls on the elderly and the poor — in large part due to economic inequality.

One of the most egregious cases in recent U.S. history was Hurricane Katrina, which in 2005 devastated New Orleans, particularly the Lower 9th Ward and St. Bernard Parish to the southeast of the city. The storm killed nearly 2,000 people and caused more than $100 billion in damage. But it cost far more to the people in those communities who had nowhere to go during the storm, nowhere to live in the aftermath, no ability to get to work (if they even had jobs after the storm destroyed so many local businesses), and no money to rebuild. Living below sea level is dangerous enough — living below both sea level and the poverty line is even more so. This is where economics enters.

Property in Union Beach, N.J., where a house used to be; this picture was taken almost a year after Hurricane Sandy hit. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Erin Cadigan.

Estimating economic losses after a natural disaster is even harder than estimating deaths and injuries. Again, these losses have very little to do with the loss of human capital. It is extremely rare for labor markets to be so impacted by a disaster that economic productivity is impaired for lack of labor — at least not beyond the local level.

What almost all natural disasters do is to destroy capital stocks — manufactured capital, buildings and such. Just about all manufactured capital has value, but not all capital contributes to the economy in the same way. For example, consider the holiday home of a very wealthy person versus a factory, both valued at $50 million. There is a business in luxury homes that is not insignificant, but the vacation home is mostly unoccupied and employs few people. Compare that to the factory, which employs 200 workers and produces useful things that many people need. Though the value of these two capital assets is the same, the factory is far more productive than the home, and would be a greater loss to the economy if it were destroyed. Thus, it is important to note that capital lost in a disaster is only disruptive to an economy in the longer term to the extent that the capital lost is actually productive capital. To a person, of course, even though a home isn’t economically productive (unless one runs a business from it), it is still valuable. No wonder economics is called the “dismal science.”

Hurricane Sandy deeply impacted local communities, such as Breezy Point, N.Y. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/ovidiuhrubaru.

It is not hard to imagine a home valued at far more than $50 million dollars and a factory at far less. If many such homes were lost in a disaster, the economic loss may appear very large, but in fact, it would still likely make little difference to the economy, whereas losses valued at a lesser amount (like the factories) might have a greater impact. So, just as fatalities do not predict economic losses, built capital losses are not a good predictor of economic losses either.

This tells us why the aggregate economy of New York hardly noticed Hurricane Sandy, disastrous though it was (it was the second-costliest tropical cyclone, after Katrina) for local economies and for hundreds of thousands of people. Most of the capital that was destroyed comprised modest homes and small businesses. New York has a service-based economy (as do almost all highly developed countries, including the U.S.), and it can easily survive the loss of a comparatively small number of modest homes and small businesses. It’s not that they have no value; they certainly do. They were very valuable to their owners, but their loss did little to slow the engine that drives the New York economy, much less the U.S. economy.

This sort of consideration also tells us why economic losses, if valued in this way, can seem very small in poorer countries because their value is technically low, even though the impact of those losses can be much harder for poor countries to absorb. The same thing can be said for poor people in wealthy countries. That takes us back to the issue of how disasters disproportionately affect the poor and the elderly.

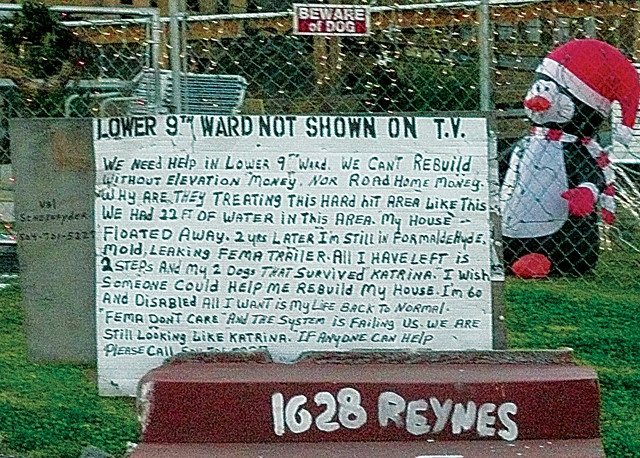

A Lower 9th Ward resident's plea, years after Katrina, shows a house not yet rebuilt and no money to rebuild. Credit: Chris Anderson, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

While it might look from the outside like we are “all in it together” when disaster strikes, we really are not, at least not for long. In recent years, issues of inequality have become more prominent and more urgent. Income inequality has rocketed to historic highs. The rich really are getting richer (and fewer in number), the middle classes are sliding backward, and the poor are going nowhere.

French economist Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics says it’s simple: The rich have capital and know how to invest it and get rates of return of at least 10 percent with very little actual work involved. The middle classes, who don’t have much capital, gain at a rate something more like bank interest or salary growth (a fraction of capital growth). And the poor, having no capital and minimum wage jobs, are stuck with no growth at all. So most people gain at about the rate of the economy as a whole, and the rich and the poor can’t help but get further and further apart. Other economists, such as Columbia University economist and Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz, suggest there’s more to it than that though. Stiglitz says the bigger issue is that the super-wealthy elite have so much control over government and the main sources of capital generation that they can rig the system to be sure they always benefit.

Where Jakeabob's Bay restaurant in New Jersey used to stand. It was destroyed by Hurricane Sandy. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Erin Cadigan.

When disasters strike, preexisting inequalities worsen; disasters are multipliers of inequality. For instance, if a disaster is on its way, the wealthier among a population, who are almost always better-educated, have a greater understanding of what they should do to prepare. They can understand and assess what the Weather Channel is advising, interpret maps, or ask trusted friends who may know more than they do. Information flows quickly and easily across the ether of the internet. Those people don’t need to wait to be told they should evacuate; they can make their own decisions and drive out ahead of the traffic jams to stay with friends or in hotels they can afford despite jacked-up prices.

Poorer, less-educated people have a harder time knowing how to interpret information and frequently don’t trust their government. (Few people will heed the warning from a government that has done little for them in the past.) And few of those people have the means to evacuate anyway.

In the case of Katrina, for example, when the city of New Orleans was told to evacuate, more than 100,000 people — out of about 500,000 — had no access to cars to use to evacuate. A similar situation played out last February when the Oroville Dam in California threatened to break through an emergency spillway and flood several cities and smaller communities: Almost 200,000 people — many lower-income — were told to evacuate, but how and to where? Many people heeded the evacuation order: We saw whole families sleeping in cars because they couldn’t afford a hotel. And we saw a story about one young mother and her 18-month-old who were trying to hitchhike out of Oroville because they didn’t have a car or any other way out of town. We also saw people who didn’t leave — some because they chose to stay to protect their possessions, some because they had no way to leave. Others may not have been aware of the evacuation order. Everyone lost income from jobs they couldn’t do and businesses that were closed for several days while officials tried to fix the dam. Had the dam burst, how many lower-income or elderly people would have perished because they had no disposable income to get them someplace safe? Thus, we see that preexisting inequalities have a strong hand in determining the immediate outcomes of a disaster.

The situation doesn’t get better when we consider what happens after the disaster, at the back end. The well-heeled more often return to homes that have been little damaged because, by and large, their homes are sturdier and situated in less risky locations. Their jobs often do not require them to be at any particular place, something that’s more characteristic of service economies compared to manufacturing economies. Their houses are insured and they have cash in the bank so they can get repairs going right away. Poor people most often lose paychecks if they cannot show up to work or lose their employment altogether. Once permitted to return, they will find their homes trashed or declared unlivable. Their homes are often uninsured, but even if they are insured, the value the people get for their homes after wrestling with insurance companies for months is far less than what it would cost them to rebuild. Worse still, as happened after Katrina, they may not be allowed to rebuild at all because the places they lived may well be deemed unsafe — below a flood level or too close to a fault, for example.

The damaged spillway from the Oroville Dam — a disaster in the making that did not materialize as workers were able to prevent the entire spillway from giving in and seriously flooding areas downstream. Credit: both: Dale Kolke/California Department of Water Resources.

Scientists have good intentions when it comes to studying natural disasters, but we are unintentionally complicit in the cycle that handicaps the poor in the aftermath of storms, floods, earthquakes and other events. Think about why the poorest people are living in dangerous locations, like swampy low-lying coastal regions, in the first place. They are living in these dangerous locales because the land is less valuable and thus more affordable. Wealthier people know these areas are dangerous and have occupied the safer places — often, literally, on higher ground, which makes for more expensive real estate. Or poor people are there because they can’t go anyplace else. Or they’re living in dangerous places because they simply don’t know any better.

Earth scientists are very much aware of the hazards of living in flood, fault or landslide zones, but how would the poor know? Scientists don’t communicate well with the public, especially the poor. While the dangers of an impending storm or living near a fault or on an old landslide deposit may seem obvious to scientists and others in the know, they can be far less obvious to people who haven’t been exposed to information about such hazards. And there are few social signals. Real estate agents often say nothing, nor do those providing building permits. Surely, one might think, if I can get a building permit for a site, it must be safe to build there. After disasters, scientists have a habit of wagging their finger at the residents and asking why people were living in such dangerous places in the first place. Then we suggest that the residents should be moved out or kept out — it’s the victims who get the blame.

When it actually comes to rebuilding, the inequality gap grows even larger. Rebuilding requires an influx of capital, something to which the poor have no access, and to which the middle classes have limited access. But everywhere in the world, no matter how rich or poor the country, there are what I call the “disaster profiteers”: wealthy, well-connected individuals or groups who are part of, or very close to, the government and are very influential in how capital provided for reconstruction is spent.

Almost invariably there are propositions made by members of this group to take advantage of what nature has done and use relief capital to begin a plan for urban renewal that was, in many instances, sorely needed before the disaster. Disaster is seen as “providential.” Low-income areas are usually the most damaged. Therefore, they must be the most dangerous and should not be reoccupied, these people argue.

Scientists will agree, though for very different reasons. These areas could be made into parks and golf courses or returned to nature — places where no one actually lives but can provide relaxation for those who have time to relax and can afford to golf: not to be used by those displaced to make way for these amenities. The BNOB (Bring New Orleans Back) plan for New Orleans was just such a plan and was described as a “massive red-lining exercise wrapped around a land grab” by former mayor Marc Morial. BNOB was meant for residents of an imagined new and better New Orleans, not the residents of the old city.

This apartment complex in Pacifica, Calif., was evacuated due to landsliding. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/lightstalker.

There is every good reason to want to use the opportunity of rebuilding to make a damaged place a better place. But there is no case, that I am aware of, in which the better place that emerged has been better for everyone. Most commonly, it is better for a few who were well off to begin with.

Unwittingly, scientists can make matters worse. We are too quick to condemn inhabited places as unsuitable for people to live, and then leave the problem to others to act on what we say. Unfortunately, those who take charge of coming up with solutions tend to regard the places declared unsuitable by scientists as problems without solutions, and they are ignored in favor of problems where solutions can be recognized and achieved, like improving the central business district or tourist attractions. The poor are neglected and the wealthy do better; inequality increases.

It is a dilemma for those of us in the natural sciences. It isn’t irresponsible to say, “that’s not my job.” After all, that’s not what natural scientists are trained to do. Unfortunately, ensuring that disasters do not lead to greater social inequity seems to be no one’s job, yet it undermines our work in providing predictions. Scientists have recently started taking strong positions in the political arena as part of the global debate on climate change. They will readily discuss the merits of carbon taxes versus cap-and-trade and other economic measures — subjects in which they are not trained. It’s time we made our voices heard on the injustice of natural disasters.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.