by Bethany Augliere Thursday, January 17, 2019

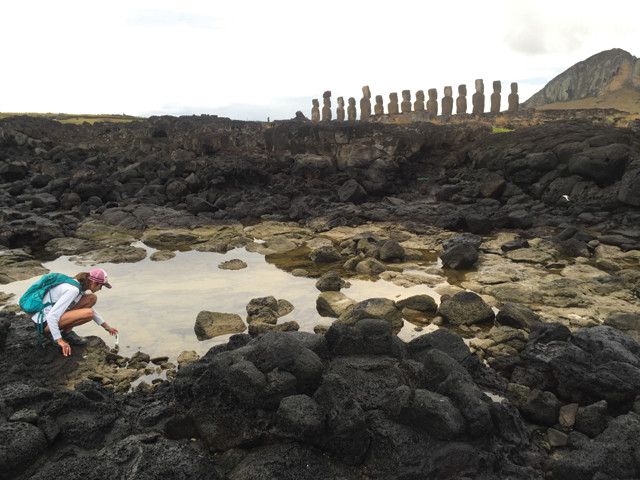

Graduate student Tanya Brosnan, who led a recent study of coastal seeps — where fresh groundwater flows into the ocean — on Rapa Nui (Easter Island), carries out conductivity measurements near Ahu Tongariki on the east side of the island. Credit: Carl Lipo.

The remote Chilean island of Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, is famous for its 961 giant stone statues and monuments, erected between 1200 and 1600. Called moai, these statues have been a mystery for years, especially considering just a few thousand people inhabited the small, resource-limited Pacific island nearly 3,700 kilometers west of Chile. “Why did people put the statues where they did?” asks Carl Lipo, an archaeologist at Binghamton University in New York. The answer, according to new research, may have something to do with the civilization’s water supply.

Easter Island is a dry volcanic island with little surface water, other than two crater lakes, and porous soil that doesn’t hold much groundwater. However, rainwater that soaks into the ground is known to flow downhill and discharge at points along the coastline, leading Lipo and his colleagues, Tanya Brosnan and Matthew Becker of California State University, Long Beach, to wonder if this water was drinkable.

The team spent two to three weeks on the island during winter 2014, and then again in summer 2015. During the first expedition, they focused on locating sources of freshwater that might have been available to the island’s early inhabitants, mapping streams, springs, lakes, wells, pools and coastal seeps.

On the second expedition, the team focused specifically on the coastal seeps, where fresh groundwater flows into the ocean. Due to accessibility and modern development, the study area included only the eastern portion of the north and south coasts. The scientists trekked on foot, taking salinity and temperature measurements of seawater every 10 meters along the shoreline. If they detected brackish water with less salinity, they took more closely spaced measurements to map the discharge sites in more detail.

The researchers discovered that potable groundwater poured out at the coastline, notably in areas associated with archaeological remnants and artifacts, including moai, suggesting the islanders located their settlements and statues near these water sources. Evidence of such human activity is not currently known from around the crater lakes. The findings show that this water at the coast is brackish but drinkable, the team reported in Hydrogeology Journal. “Water is such a critical resource that people will learn the landscape and find where it’s available,” Lipo says. “They’ll find it because they have to.”

Why giant stone statues called moai are located where they are on Rapa Nui has long been a mystery. Credit: public domain.

The researchers “provide near-complete spatial coverage of freshwater sources for the eastern half of the island using well-established geochemical and survey techniques,” says archaeologist Robert DiNapoli of the University of Oregon, who was not involved in the study. “This study contributes to our understanding of how people managed to live and thrive on this tiny, remote and marginal island by accessing water from a previously underappreciated source — coastal freshwater seeps,” DiNapoli says.

“It’s really a landmark study — I think it’s going to be very important,” says Terry Hunt, also an archaeologist at the University of Oregon who was not involved in the study. “Easter Island gets so much attention that when we understand a critical piece of the puzzle it has real significance.” Before this study, there wasn’t much serious consideration about the available freshwater compared to other resources from agriculture or fishing, Hunt says, noting that it has generally been assumed that Rapa Nui’s inhabitants traveled across the island to the lakes to get water, which doesn’t make as much sense.

The Rapa Nui had no pottery or means of transporting large amounts of water. And in times of drought, collecting rainwater would not have been enough, Lipo says. The results of the new study suggest that the Rapa Nui people likely drank brackish water from the coastline, he says. This corroborates reports from Europeans who first made contact with the islanders that stated that the Europeans saw the people drinking seawater, Lipo says, but we know of course that it wasn’t seawater. Even today, he says, you can see horses drinking water at the shore, “because animals know where to find water.”

Understanding the Rapa Nui people’s use of water helps correct the long-perpetuated, but incorrect, narrative about the island and how its civilization eventually faded, Lipo and other Easter Island researchers say. The Europeans who encountered the island were baffled by how the Rapa Nui people could thrive with so few natural resources. And it has long been suggested that the islanders overexploited their resources, Lipo says. But the consensus, he notes, is that the Rapa Nui died off largely from disease introduced by Europeans.

“This study is one more piece of evidence that shows us how the island was sustainable and how the ancient culture adapted and [the inhabitants] were wise stewards of the island,” Hunt says.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.