by Chris Iovenko Friday, August 31, 2018

The Netherlands has, for centuries, dealt with flooding and high waters by developing innovative water management techniques and technologies, and in recent years, other countries have been tapping this Dutch expertise. Here, the Maeslantkering, a massive moveable storm surge barrier that can be engaged to protect the city and port of Rotterdam from flooding, sits open, with its two swinging gates resting on dikes on either side of the Nieuwe Waterweg channel. The barrier, completed in 1997, was part of the last phase of the Netherlands' decades-long Delta Works project. Credit: shutterstock.com/GLF Media.

In early 2017, scientists from NOAA and other U.S. research institutions announced that new data had led them to raise the upper estimate of projected global sea-level rise by the end of this century to 2.5 meters. That’s considered the extreme scenario and would require a catastrophic melting of land-based ice sheets and glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica. However, it doesn’t take anywhere near that much sea-level rise to cause havoc. Global mean sea level has risen about 8 centimeters in the last 20 years, contributing to dramatic increases in coastal flooding. For example, nuisance flooding in U.S. coastal communities has increased by 300 to 900 percent in recent decades due to the increased intensity of storm surges, according to NOAA’s National Ocean Service. And it’s not just nuisance flooding that’s a problem.

The 17 tropical storms of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season, including 10 hurricanes, caused an estimated $282 billion in damage in the U.S., ranking as the country’s most destructive and expensive hurricane season to date; again, larger storm surges caused by higher seas was part of the reason the damage was so great. Rising oceans are no longer just a future threat; the problem is here and will only get worse over time. So, what to do? Where to turn? Enter the Dutch.

Dutch expertise in water management is as old as the Netherlands itself, and as global seas rise, the Dutch are still on the front lines in dealing with flooding and sea-level rise. This prowess is not only helping them in their own efforts, but now they “are going all around the world consulting and selling their engineering expertise,” says journalist Jeff Goodell, author of the 2017 book “The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities, and the Remaking of the Civilized World.” They are “trying to export that expertise; it’s their growth industry. … It’s their Silicon Valley.” And coastal cities in the U.S. and elsewhere are hoping Dutch ingenuity will work for them as well in fighting back the encroaching seas.

Water-pumping windmills were an early technology used by the Dutch to drain swampy areas — which often lay below sea level — and create polders, dryland plots surrounded by dikes. Credit: Henk Monster, CC BY 3.0.

The Netherlands is situated in a low-lying delta formed by the outflow of three major rivers: the Rhine, the Meuse and the Scheldt. In accordance with the Dutch saying that “God created the world and the Dutch created Holland,” the country is in large part an engineered landscape reclaimed from swamps and marshes. One-third of the Netherlands is below sea level, and two-thirds is vulnerable to flooding. Dutch identity and society arose from the common need to push back against the sea.

“The Netherlands as a nation was born fighting the sea,” says Adriaan Geuze, founder of the Dutch design firm West 8. “The DNA of Holland is to live in a delta, to live on the coastal plain and to live in the swamp. The entire Dutch culture is born from this notion.”

In the 13th century, the people of the Netherlands began developing strategies and technologies to deal with flooding. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

In the 13th century, after decades of disastrous inundations by floods and storms, the people of the Netherlands organized around the communal need to keep the water out, developing strategies and technologies to deal with flooding. Water management innovations, such as the now-iconic 15th-century polder windmills, which pumped out swampy areas, often lying below sea level, proliferated. Over time, some 3,000 polders, or dryland plots surrounded by dikes, were created.

The Dutch became famous for their early mastery of coastal engineering and water management, which for centuries largely kept them safe behind barriers and dikes. This sense of safety was sharply eroded in early 1953, however, when the North Sea broke through the protections, flooding more than 2,000 square kilometers of land and killing 1,835 people overnight.

Willem Schellinks' painting, "De doorbraak van de Sint Anthonisdijk bij Houtewael," depicts the breach of a dike in the village of Houtewael near Amsterdam in 1651. Credit: public domain.

“The 1953 flood for [the Dutch] was like Sept. 11 was for us, but [caused] by nature,” says John Englander, an oceanographer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and an independent sea-level rise consultant. “They woke up after that event and said, ‘We are going to engineer our way [out of this] so that this doesn’t happen again.'”

And engineer they did: In the aftermath of the flood, the Dutch redoubled their efforts to battle the sea, creating an enormous flood-control system known as the Delta Works. A modern engineering marvel, the Delta Works — built between the late 1950s and the 1990s — consists of nine dams and four storm barriers that have closed off estuaries and substantially reduced the Dutch coastline by about 700 kilometers. Delta Works has served the Dutch well for decades, but extreme flooding in the ‘90s caused mass evacuations and fueled rising concerns about climate change and sea-level rise. Dutch water managers saw limitations to “hard engineering” approaches like dikes and barriers in a rapidly changing and increasingly unpredictable climate, so they took a vigorous new approach.

Floodwaters swamp a coastal town in the Netherlands during the North Sea Flood of 1953, which produced record storm surges and killed more than 1,800 people. Credit: U.S. Agency for International Development.

“In 1992, the Dutch were able to pass a national flood policy that obligated them to protect against floods and gave them a governing structure as well as resources” to do so, says Shana Udvardy, a climate resilience analyst with the Union of Concerned Scientists. “It helped shift the paradigm toward the questions of ‘How are we going to accommodate flooding? How are we going to afford it?’” Udvardy says.

The right of the Dutch population to be protected from flooding was written into the constitution, and the Netherlands adopted a very high national standard for flood safety. Their flood protection measures are designed to defend the heavily populated and industrialized western part of the country from 10,000-year floods (those thought to have a 0.01 percent chance of occurring in any given year); less populated areas, meanwhile, have protections designed to guard against a 4,000-year flood. In the U.S., by comparison, a 100-year flood standard (a much lower standard relating to events thought to have a 1 percent chance of occurring in any year) is often the norm for guiding relevant safety and insurance policies.

In addition to building more walls and dikes, the Dutch also began applying a more long-term, holistic perspective about flooding that factored in scientific data about the changing climate. The crowning achievement of this costly effort is known as Room for the River, a massive $3 billion project initiated in 2006 that involves some 40 different infrastructure projects along Dutch rivers and waterways. At the heart of the project is the idea that instead of keeping water at bay, space can be allocated to safely accommodate flooding. Dikes and other obstructions are removed, and flood channels and floodplains are broadened and deepened.

The 30-kilometer-long Houtribdijk between the towns of Enkhuizen and Lelystad was completed in 1975 as part of the Zuiderzee Works, a project begun in about 1920 to dam and reclaim land from the shallow Zuiderzee Inlet. Credit: Snempaa, CC BY-SA 4.0.

In Noordwaard, near Rotterdam, a large polder has been repurposed as a reservoir for floodwater. And in the 2,000-year-old town of Nijmegen, a dike was moved back and a new bypass channel was dug for the river Waal. Ambitious in scope, the flood-control program in Nijmegen also acted as a catalyst for broader urban regeneration there, including the addition of an urban park on an island and a riverfront promenade. Adding urban improvements and amenities built crucial local support for the plan.

These projects are typically expensive — the project in Nijmegen cost $500 million — and often require sacrifices; people are displaced from homes in flood zones and formerly productive land is fallowed or repurposed. In return, natural floodplains are restored to serve as sponges during floods. The rest of the time, these areas can be used for recreation or allowed to return to a natural state. This “softer” approach to water engineering issues has gained traction with designers, planners and architects around the world.

The 9-kilometer-long Oosterscheldekering, completed in 1986 as part of the Delta Works, is the largest storm surge barrier in the Netherlands and features sluice gates that can be opened or shut to allow water to pass through or to block it. Credit: Bert Kaufmann, CC BY 2.0.

“There is a kind of Zen of Engineering, if you will, that has to do with subtler ways of absorbing the impact energy of anything,” says Guy Nordenson, a structural engineer and professor at the Princeton University School of Architecture. “The questions are: How do you absorb impact? How do you dissipate energy? How do you do things in ways that are creative and, in some cases, involve nature?”

In addition to techniques that confront flooding, some modern Dutch ideas about how to live with water are more experimental: In Rotterdam Harbor, for example, a floating dairy farm, replete with 40 cows and 6,000 chickens, is being constructed by a private consortium. And a floating forest that consists of salt-resistant trees housed in buoys has already been installed in the harbor.

Twenty Dutch Elm trees uprooted from parts of Rotterdam during construction projects were replanted and installed as a "bobbing forest" in the city's harbor in 2016. The effort is primarily meant as an art installation, but is also seen as a model for future innovation and sustainability projects. Credit: shutterstock.com/hans engbers.

One experimental project in the Netherlands that is starting to catch on elsewhere is the Zandmotor, or Sand Engine — a 1-kilometer-long, hook-shaped sand peninsula that was built in 2011 along a stretch of coastline at Ter Heijde in South Holland. In a single operation 10 kilometers offshore, dredgers collected 21.5 million cubic meters of sand, which was then deposited in the designated area. Over time and by design, waves and tides slowly disperse the sand and naturally replenish nearby beaches. This conceptually simple experiment, also known as sandscaping, has performed as designed, preventing beach erosion. It has also been more efficient and economical, as well as less disruptive to the beach and to wildlife ecology, than a traditional approach such as regular sand replenishment. Its success has not gone unnoticed; another sand engine is now, with Dutch help, being constructed along the North Sea coast in Norfolk, England, an area where severe beach erosion threatens coastal towns and industry.

From Delhi, India, to Wuhan, China, to São Paulo, Brazil, cities around the world have begun to turn to the Dutch for help with water management strategies. The Dutch, in turn, have been eager to export their technology and expertise; in the Netherlands, water management is a $5.5 billion industry annually.

As part of the Room for the River project, a dike was moved back and a bypass channel (left waterway in the photo) was dug along the River Waal at Nijmegen to help protect the surrounding areas from excess floodwater. Dredging of the channel, seen here in summer 2015 toward the end of its construction, also created a new island, which now hosts an urban park. Credit: Alamy.com/frans lemmens.

Cities in the United States, in the wake of punishing natural disasters, have also turned to the Dutch both for expertise and inspiration. Following the devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005, a delegation of architects, city planners and politicians from Louisiana, including architect David Waggonner, visited the Netherlands.

“Dutch society is organized around its physical challenge, and it’s organized to take advantage of its physical location,” Waggonner says. “Room for the River is illustrative of what the Dutch can do, which we seem to find impossible: create a project that improves safety, improves quality of life and compensates people fairly. It’s a win, win, win.”

Starting in 2006, Waggonner’s firm, Waggonner & Ball Architects, helped partner Dutch planners with New Orleans’ public officials through a series of workshops and publications that came to be called the Dutch Dialogues. The Dutch Dialogues introduced New Orleans to new thinking on, and approaches to, water and engineering issues. Although the Dutch Dialogues ended in 2011, the collaboration helped give rise to the city’s new resilience strategy.

Emblematic of New Orleans’ new approach is the Gentilly Resilience District. Created in partnership with Dutch designers, the district is a comprehensive flood management strategy for Gentilly, an ethnically diverse middle-class neighborhood. In the context of urban planning, resiliency describes systems adapted for disruptions that can bounce back quickly in the wake of natural disasters. In Gentilly, some of the resilient design elements being developed include water-permeable streets and sidewalks, medians between streets and former woodlands designed to function as stormwater holding facilities, and an old convent that’s to be transformed into a “water garden” and recreation area that can also hold up to about 38,000 cubic meters of stormwater.

When Hurricane Sandy hit the East Coast in October 2012, it was the second-deadliest and -costliest hurricane in U.S. history (it has since dropped to fourth in both measures behind 2017’s Harvey and Maria). The sheer destruction it created and the vulnerabilities it revealed were wake-up calls to many about the dire threats posed by climate change.

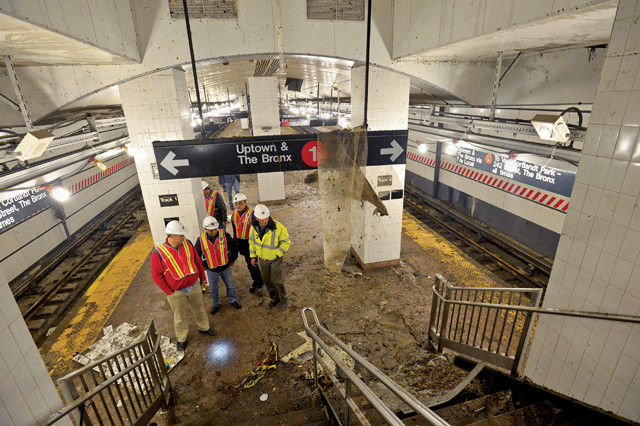

Many subway stations and tunnels, including the South Ferry subway station in Lower Manhattan, seen here in November 2012, were heavily damaged by floodwater during Hurricane Sandy. Credit: Metropolitan Transit Authority/Patrick Cashin, CC BY 2.0.

“Sandy wasn’t the exception; Sandy was the announcement of a new standard,” writes Henk Ovink, special envoy for international water affairs for the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in his 2018 book, “Too Big: Rebuild by Design: Transformative Response to Climate Change.”

In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, President Obama allocated $60 billion to help the East Coast recover from the disaster, and updated flood standards for federal agencies to allow for the inclusion of climate science and sea-level rise data to help determine flood risk regulations (rules since rescinded by President Trump). The Obama administration saw in the effort to rebuild and recover from the disaster an opportunity to better prepare the region for the perils of future storms and flooding. The plan was to rebuild better and smarter, with resiliency in mind. As part of this effort, Obama sent Shaun Donovan, then secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), to the Netherlands to observe Dutch flood-control and prevention measures. There, Donovan met Ovink, who was eager to show off the Dutch prowess in dealing with water. Donovan was impressed by what he saw, and he and Ovink eventually became partners. Ovink moved to the U.S. and oversaw a multifaceted planning and design competition called Rebuild by Design, which was launched by the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force in June 2013. Rebuild by Design was a complex and ambitious undertaking that sought to integrate a wide range of government entities, nonprofits, community organizations and stakeholders in Connecticut, New Jersey and New York. The concept was to focus on design and let the design dictate specific projects and policy.

The Zandmotor, or Sand Engine, at Ter Heijde in South Holland seen in July 2015, four years after it was created. Credit: Joop van Houdt/Rijkswaterstaat.

“At the core of Rebuild by Design [was] the design approach so familiar to those of us in the Netherlands,” Ovink writes in “Too Big.” “Design can, and should, create a narrative that can seduce and convince people, informing and uniting them around complex decisions that lead to action.”

Rebuild by Design produced a slew of high-profile and thought-provoking ideas for waterfront projects, seven of which have been funded by the affected cities and states, often with additional federal aid. Of the funded projects, New York’s BIG U is the highest profile and arguably most ambitious. Not only did Hurricane Sandy wreak havoc on New York and its environs, it flooded portions of Manhattan’s underground infrastructure, including many tunnels and subway stations, which filled with saltwater that corroded electrical systems.

The catastrophic flooding in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina led the city to partner with Dutch designers to create a new resilience strategy. Credit: U.S. Navy photo by Gary Nichols.

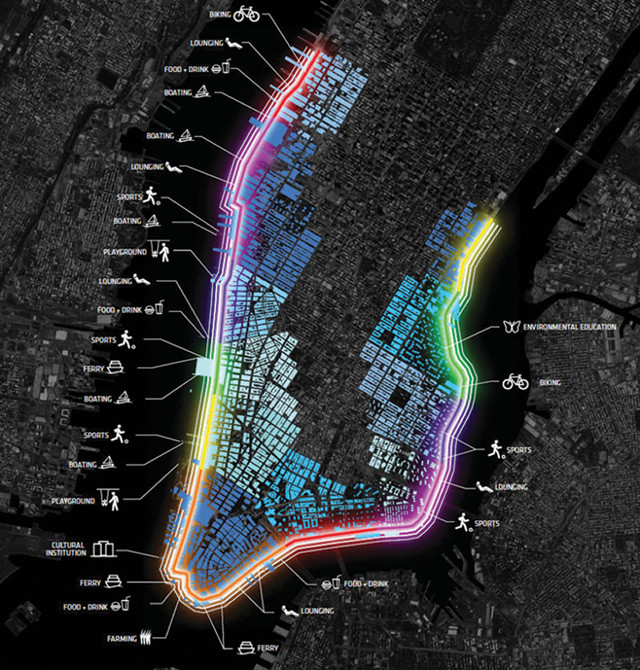

Manhattan remains very vulnerable, and the BIG U, which has already received more than $800 million from HUD and the City of New York, will be an innovative 16-kilometer stormwater barrier ringing lower Manhattan. Some features of the BIG U — construction of which has been delayed but is currently slated to begin in 2019 — would be familiar to the Dutch. Like the Room for the River project in Nijmegen, the BIG U sought input from local residents and stakeholders, and it will be much more than a traditional storm barrier. It is a multilayered system that combines a variety of storm surge barriers, from fixed berms to inflatable, pop-up barriers, as well as floodwater runoff and storage areas. It is also meant to incorporate myriad urban upgrades such as parks, benches, bike paths and vendor stalls.

Another project in New York that exhibits Dutch design influence is the recently completed renovation of Governors Island. A former fort and military base, and more recently a Coast Guard training facility, Governors Island, which sits in New York Harbor just south of lower Manhattan and west of Brooklyn, was sold to New York state and New York City by the federal government for $1 in 2003 (a small portion remains with the National Park Service). In 2010, a far-reaching plan was undertaken to remake the island as a legacy public park that would be sustainable and enjoyable for many generations to come. The Dutch firm West 8 was chosen to implement the project.

Flooding during Hurricane Sandy shut down the Queens-Midtown tunnel, which connects Manhattan to Queens beneath the East River, for more than a week. Credit: Metropolitan Transit Authority/Mark Valentin, CC BY 2.0.

“A legacy park needs to be above sea level. So, we manipulated the topography and created a new level above the 100-year flood line,” says West 8 founder Geuze. With his Dutch background, Geuze says his mentality is that “you always build above flood level. If you are an architect, you build the roof to keep the water out; that’s how I design parks and cities.”

The flat topography of the low-lying south end of Governors Island was radically altered. Carefully fortified hills were built with debris from the imploded Coast Guard buildings. While these hills protect natural elements on the island like trees, shrubs and grass from the deleterious effects of saltwater inundation, they also provide an impressive vista of New York Bay and lower Manhattan. The park’s design was tested by Hurricane Sandy and it passed with flying colors; unlike other parks in the region, Governors Island survived the storm virtually unscathed.

The BIG U, construction of which is currently slated to begin in 2019, is intended to ring Lower Manhattan with 16 kilometers of stormwater protection involving different types of barriers as well as floodwater runoff and storage areas. Credit: BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group.

One lesson from the Netherlands’ experience is that not only can big public investments in flood-control infrastructure work, but they can be more economical than responding after a disaster. Historically, however, the U.S. has relied more on expensive disaster recovery than on programs and infrastructure meant to prevent or mitigate flood-related disasters.

“Most of our funds are spent after a disaster. The record-breaking year for disasters was 2017; it cost taxpayers a total of $300 billion,” Udvardy says. And the cost of weather- and climate-related disasters in the U.S. is trending up, in part due to the rising frequency of damaging weather events and to increasing amounts of vulnerable infrastructure. “We are hoping to turn the tide on this front because we know that spending money now on mitigation activities can reduce the cost in the future,” she says. Udvardy cites a recent study by the National Institute of Building Sciences that found “on average, we can save $6 in future disaster costs for every dollar we spend on federal disaster prevention. It’s truly valuable to start bumping up the different budgets that have pre-disaster mitigation programs.”

Although many architects, experts and city planners around the world laud the Dutch efforts to innovate solutions to sea-level rise and flooding, others are cautious about the temptation to oversimplify the problems of sea-level rise, or to think that we can engineer our way out of any problem.

The BIG U is also meant to incorporate urban upgrades such as parks, benches, bike paths and vendor stalls. Credit: BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group.

“We certainly want to applaud the Dutch for their good engineering, but the fact is if sea level is going to be 5 or 10 feet [1.5 to 3 meters] higher, there isn’t going to be any simple answer or engineering fix,” Englander says. “It’s a bigger problem than most people have stopped to think about.” The sheer size and complexity of sea-level rise, and the fact that 40 percent of the world’s population lives within 100 kilometers of a coastline, preclude one-size-fits-all solutions.

The greatest lesson to be learned from the Dutch is perhaps less about engineering and more about mindset and culture. “It’s easy just to talk about technological and engineering solutions, but a lot of the problems surrounding sea-level rise are legal and political. The Dutch have a legal and political system that is united around dealing with water issues; they’ve been doing it for a thousand years,” Goodell says. “Here in the U.S., it’s not just getting the right engineering ideas and figuring out what technology or design ideas we’re going to use. It’s that our legal system and our political system are just not adapted to thinking about sea-level rise in any kind of holistic way.”

According to Goodell, the challenge for Americans is a cultural one; the issue needs to be viewed not as a future problem for isolated municipalities or regions but as a current national crisis threatening our coastlines. The Netherlands’ culture of innovating water management and flood-control measures, as well as the country’s huge public investments in disaster-mitigating infrastructure, could be instructive in how to navigate coming climate change-related challenges.

The view of lower Manhattan from the renovated south end of Governors Island in New York Harbor. Credit: MusikAnimal, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Of course, the Dutch cannot export their history or culture, but as the seas rise, U.S. coastal cities will need to develop more flexible and innovative approaches to accommodating and responding to encroachment from seas and rivers.

In the short term, some cities, like New Orleans, New York and Norfolk, Va., are ramping up flood-control-related investment, planning and preparedness in combination with forward-looking design strategies. In that sense, the Dutch offer a model for innovative and common-sense approaches. The Dutch design influence on U.S. projects such as the Gentilly Resilience District, the Rebuild by Design projects and Governors Island certainly represents important steps in the right direction. Twenty years from now, floating buildings, forests and dairy farms may not seem so fanciful.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.