by Mary Caperton Morton Wednesday, January 18, 2017

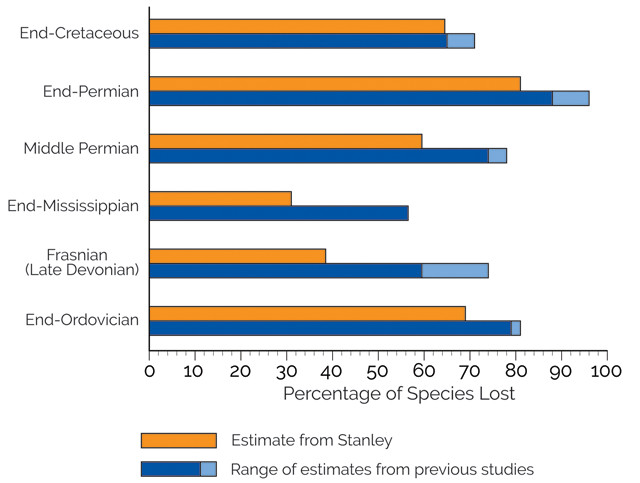

Estimates of species losses during six mass extinctions are lower when background extinctions are subtracted from previous estimates. Credit: Steven Stanley.

The end-Permian extinction, nicknamed the “Great Dying,” is thought to be the deadliest mass extinction in Earth’s history. Many textbooks claim that up to 96 percent of marine life died out during this event, but a new study suggests this cataclysmic number has been overestimated.

“Some paleontologists have been stuck on this 96 percent number for a long time. It sounds dramatic to say life nearly died out, but they’re not taking into account background extinctions,” says Steven Stanley, a paleontologist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and author of the new study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Not all extinctions occur in mass die-offs, which are often used to mark the ends of geologic periods. Species also go extinct on a regular basis due to natural selection and competition with other organisms. “This phenomenon of background extinctions is known and widely accepted, but this is the first time that somebody has tried to separate those numbers out from a mass extinction,” says David Bottjer, a paleontologist at the University of Southern California who was not involved in the new study.

Stanley chose to focus on the end-Permian extinction because it is the largest-known mass extinction and marine fossil records provide a clear record of the event. As for the cause of the die-off, “consensus centers on volcanic eruptions, specifically large igneous provinces that resulted in an enormous amount of volcanism in a relatively short amount of time,” Bottjer says. These eruptions produced copious amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, leading to global warming as well as a noxious atmosphere and acidified oceans, which affected organisms both on land and in the oceans.

To get a better idea of the background extinction levels leading up to the mass die-off, Stanley developed a statistical method for estimating the rate of background extinctions at the genus level throughout geologic time. Statistical methods are necessary for studying background extinctions because these extinctions are often hard to see in the fossil record — many species live and die off without leaving any fossils at all. “I wrestled with this idea of calculating background extinctions for about a year,” Stanley says. “I was starting to feel like a physicist or a mathematician working out an impossible equation.”

Eventually, he worked out an equation that described a correlation between background extinctions and time: Essentially, the longer the time interval between mass extinctions, the more background extinctions. He then applied this equation to the Late Permian time interval prior to the end-Permian extinction and found that many of the species generally considered to have gone extinct during the Great Dying may actually have died out before it began. By subtracting these earlier extinctions from the 96 percent figure, he came up with a lower die-off rate of 81 percent of marine species during the end-Permian extinction.

The difference is not enormous, Bottjer says, “but it’s certainly significant. [Stanley] has done a great service to the community by wrestling with this issue of background extinction levels. It’s not an easy thing to quantify.” Stanley also applied his methods to six additional mass extinctions, including those at the end of the Ordovician, Devonian and Cretaceous periods, and found a similar pattern in each: Pulling out background extinctions that likely preceded the main extinction event significantly lowered loss estimates.

“Knowing more accurately how severe mass extinction events were helps us better understand what caused them,” Stanley says. For example, previous estimates that roughly 96 percent of marine life died out suggests the oceans were nearly unsurvivable. But the new estimate closer to 81 percent suggests that at least some pockets remained habitable throughout the die-off. “Many orders of marine animals survived. If you hear 95 percent, it sounds like everything almost died out,” he says. “[The Great Dying] was severe but it wasn’t nearly the end of the world.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.