by Bethany Augliere Thursday, October 20, 2016

Kayla Iacovino stands on the crater rim of Mount Paektu Volcano in China, with a view of North Korea in the background and Lake Chon in the summit crater. Credit: Kayla Iacovino.

When Kayla Iacovino enrolled as a freshman at Arizona State University in 2005, she thought she might become an astronaut. But, after a field trip to outcrops in northern Arizona during her first semester, she became hooked on geology.

In her sophomore year, the school sent out an email to all its students titled “Get Paid to Melt Rocks.” Intrigued, Iacovino interviewed for the position with igneous petrologist Gordon Moore and, to her surprise, got the position. It launched her career as an experimental petrologist and volcanologist — a path that has led her to volcano summits around the world.

During her undergraduate education, Iacovino worked for three years doing research with Moore. She studied the composition of rocks erupted from Mount Erebus, the second-highest volcano in Antarctica and southernmost active volcano in the world. After graduating, she attended the University of Cambridge in England for her doctoral work, and continued research on Mount Erebus.

Recently, Iacovino explored a new volcano, Mount Paektu in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea). As a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow with the U.S Geological Survey in Menlo Park, Calif., she became the first female American scientist to visit the poorly studied volcano, which straddles the border between China and North Korea. Paektu, which is responsible for one of largest eruptions in human history, around A.D. 946, recently began showing signs of renewed activity in the form of earthquakes. In North Korea, Iacovino and the team discovered the location of the volcano’s magma chamber, a potential site for a future explosion.

Now, Iacovino has returned to Arizona State as a postdoctoral fellow where she’s tackling questions about Earth’s global processes, particularly, how oxygen levels have changed throughout history. When she isn’t hiking up volcanoes or melting rocks in the lab, Iacovino enjoys watching and writing about all things “Star Trek.”

Iacovino recently spoke with EARTH about her adventures in the field, how rocks inform our knowledge of a volcano’s inner workings, and how science fiction can help raise awareness of science fact.

BA: What is the focus of your research?

KI: I want to try to understand what’s going on deep inside the volcanic plumbing system that’s ultimately making these eruptions happen. So I go into the field and I take samples of all different kinds of rocks that have been erupted. They represent a little piece of the magmatic depths that have been erupted, from different times, from different places within the system.

I take them back to the lab, look at them, characterize them, and then I perform experiments, where we take these rocks and put them back in the conditions where they were formed, so, really high pressures and temperatures. I’m recreating mini magma chambers in my lab, and I’ll do that repeatedly, at a ton of different conditions. Eventually, I get a result that looks like the natural rock in terms of its chemistry and the mineral composition. Then I know the conditions that created that rock.

Iacovino inside ice caves carved by hot volcanic gases atop Mount Erebus. Credit: Kayla Iacovino.

BA: Why do volcanoes interest you?

KI: Geology moves at a pretty slow pace, but volcanoes are this explosive, exciting thing, and the surface expressions of so many processes going on beneath Earth’s surface. Studying volcanoes is like understanding Earth’s most active expression.

BA: How do you get to Mount Erebus in Antarctica?

KI: The volcano is located on Ross Island, which is where McMurdo — the largest base in Antarctica — is located. You fly into McMurdo on a C-17 [U.S. Air Force transport plane] and land on the ice. There you spend some time training, like learning how to drive snowmobiles and do ice mountaineering with ice axes.

After that, we take helicopters up to 3,000 meters, and camp for a few days to acclimatize to the elevation. Then, we make the trip up to the summit at nearly 4,000 meters, which can be either by helicopter or snowmobile. You can really feel the elevation when you are up there hiking around; you lose your breath quickly and you get tired more easily.

BA: What is it like being on Mount Erebus?

KI: It’s one of the most beautiful, strange, and interesting places in the world.

Erebus is totally covered in ice and you’re at the highest peak around, so you can see for miles. The peak of the volcano is all white, except the very tip of the cone near the crater, which is black. It’s covered in all these crystals that Erebus is famous for, called anorthoclase crystals. They’re these big long black crystals that fly out of the volcano encased in glassy volcanic bombs, which are just blobs of magma, and land on the surface. Over time, the bombs erode away, leaving behind piles and piles of these crystals.

It’s also one of the few volcanoes in the world to have an active lava lake. When you walk around the rim and look down, a couple of hundred meters below, you can see this boiling, churning lake of lava.

There are frequent eruptions there. These big bubbles will rise up through the lava and burst at the surface, and usually it’ll send pieces and blobs of magma up into the air. Most of the time, they come up and fall straight back down, but every once in awhile, they make their way out of the volcano and fall into the crater rim. The eruptions are small, but they could be dangerous to a person working there.

BA: Have you had any scary experiences in the field?

KI: Oh, definitely. There are many different flavors of danger for a volcanologist; one is just the volcano itself, like eruptions. One day, I was walking around the top of Mount Erebus with a friend, for exercise and for fun. Then suddenly, we heard a boom. My first thought was “What the hell is that?” Then, I immediately remembered I’m on top of a volcano and knew exactly what it was. We turned around and ran toward the volcano, so we could see over the lip of the crater rim. Huge red incandescent blobs of magma were flying into the air and falling back down, almost as if in slow motion. That was one of the most spectacular things that I saw while I was there, and [presented] only a minor element of danger.

Iacovino at the summit of Mount Erebus in Antarctica. Credit: Kayla Iacovino.

BA: And what would you do if those flying blobs of magma were headed toward you?

KI: You are supposed to stop, and step away from anyone near you, so you don’t run into each other. And then just look up and watch it. If it starts to come toward you, you wait and then you just step out of the way. You don’t want to turn and run away because then you will have your back to it.

BA: Why were you interested in Mount Paektu?

KI: It’s in this weird place that is difficult to access, so it’s not well studied. We know that, about a thousand years ago, it had what’s called the Millennium Eruption, which was a very large eruption — one of the largest eruptions in recorded human history. And, despite that, we know very little about the eruption and very little about the rest of the volcano’s history.

Then, between 2002 and 2005, there was a seismic swarm at Mount Paektu … which can indicate that a volcano is reawakening; it can indicate that magma is moving around at depth. When people see this, they wonder if this volcano is going to erupt. To answer that, you have to have a very good understanding of the volcano’s history, its chemistry and the geometry of its plumbing system. None of these things were understood.

A minor eruption could have huge effects for the region, but an eruption on the scale of the Millennium Eruption would have global implications. At the very least, it would stop airline traffic and international trade routes, and possibly change the temperature of the atmosphere. So it has the potential to do something very, very big. In order to interpret the signals we were seeing, we had to go in and do this groundwork.

BA: What were you specifically studying about the volcano?

KI: We know from looking at the rocks that it was a high energy eruption, because rocks were found as far away as Japan. We don’t know how much gas came out of the eruption and what the composition of that gas was. If we can understand that, we can figure out the environmental impact of the eruption.

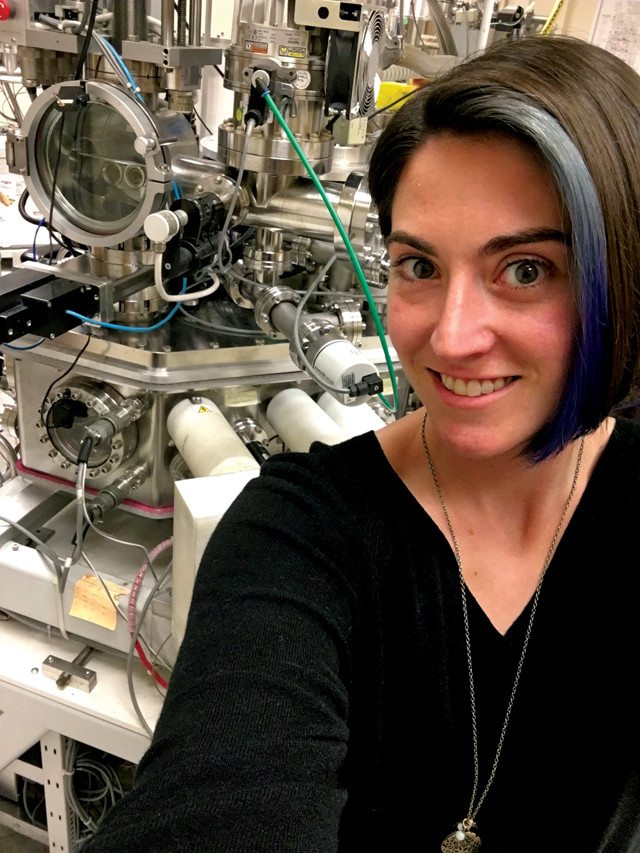

Iacovino in the lab at Stanford University in front of a Sensitive High-Resolution Ion MicroProbe, or SHRIMP, one of the many instruments she uses to analyze rock samples. Credit: Kayla Iacovino.

BA: Do you have any favorite memories from your time there?

KI: One day coming back from fieldwork, some of our North Korean colleagues had prepared a potato party. It was a small campfire, with a pile of potatoes on the fire. You pick the potatoes out of this pile and use a stick to get the leaves and dirt off them, and then dip them in a salt and spice mixture. It was amazing, sitting around in the woods in North Korea, eating a pile of potatoes with North Korean colleagues.

BA: Did you ever consider being something other than a geologist?

KI: Before I chose to be a scientist, I did a semester in film school. I’m a huge “Star Trek” fan, and I decided I wanted to go make “Star Trek.” I loved “Star Trek: The Next Generation” because it’s all about exploration and the betterment of mankind, and seeking knowledge for the sake of knowledge — all of these very noble pursuits. When I went to film school, I thought it was great, but I missed the real science. I decided that I was going to do science first, and fake science second.

BA: How do you combine the two?

KI: I’m currently editor-in-chief of TrekMovie.com, which I joined as a science writer in 2007. I got my name out there, and was introduced to Ira Flatow, the host of “Science Friday” on National Public Radio. So I wrote a blog for their website and was on the show a couple of times. I find other outlets to do feature pieces too.

I love using the creative part of my brain to tell stories. Even in my own scientific writing, I try to tell a story in my papers, but obviously using very different language.

It’s always been a huge goal of mine to try to incorporate public outreach and entertainment into the work that I do in order to reach people in ways that shows like “Star Trek” and others reached me when I was young.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.