by Terri Cook Wednesday, April 13, 2016

Eldridge Moores at the Cordelia Fault, a branch of the San Andreas Fault in the northern Coast Ranges, on a field trip for the general public in March 2010. Credit: Judy Moores.

“When Eldridge Moores was 10 years old, his family lived in Crown King, Ariz., a tiny, remote mining settlement high in the rugged Yavapai Mountains northwest of Phoenix. Money was tight and his family rarely traveled, so Moores vividly remembers a holiday road trip to visit his father’s relatives near San Francisco. The Bay Area left a deep impression on Moores, and, at the end of the journey, upon reaching the first of four switchbacks on the narrow dirt track that led up to Crown King, Moores vehemently pronounced that he would do everything he could to get out of there.

Not long after this incident, Moores’ parents purchased a house in Phoenix so that he and his siblings could attend high school in the city while his father continued to work at the mine. The teachers at his new school prided themselves on getting students who were interested in science into Caltech and indeed, Moores, who had demonstrated an aptitude for the subject, was later accepted there. It was at Caltech that he was first exposed to the study of geology, setting the stage for his remarkable career as a field geologist.

After completing his undergraduate degree, Moores attended Princeton University, where, as a graduate student and later a postdoctoral researcher, he worked closely with several founders of plate tectonic theory, including Harry Hess and Fred Vine. Moores himself is best known for his groundbreaking field mapping in Greece and Cyprus, during which he showed that ophiolites are slivers of oceanic crust and underlying mantle that formed at seafloor spreading centers and were then uplifted and emplaced onto land. Once this insight was combined with evidence for the recycling of oceanic crust in deep-sea trenches, geologists had the necessary framework to finish piecing together the theory of plate tectonics.

In 1966, Moores joined the faculty at the University of California at Davis (UC Davis), where he remained throughout his career. Following retirement in 2003, Moores continued to do service work in the geosciences, including promoting awareness of earth science in California’s K–12 curriculum, which earned him the title of distinguished professor emeritus. But to the general public, Moores is probably best known as the subject of John McPhee’s 1993 book, “Assembling California,” part of the Pulitzer Prize-winning series, “Annals of the Former World,” which chronicles the geology along U.S. Interstate 80.

Moores recently spoke with EARTH about why he dreamed of getting a job in San Francisco, how he screwed up his first field season, and what it was like working with John McPhee.

TC: What was it like growing up in Crown King?

EM: It was in the middle of nowhere. I went to a one-room school, where the number of kids varied from six to 25, depending on activity at the mines. When I was in fourth grade, I was the only person in my class. I finished the coursework by the end of December, so my teacher put me into fifth grade in the spring. I completed two years in one, and from then on, I was socially immature, short and young for my grade. That set the stage for my career.

TC: How did your father get into mining?

EM: He got into it as a teenager working for his father. In the 1930s and ‘40s, my grandfather owned a half interest in the Gladiator mine at Crown King; so after World War II my dad leased part of it from him. During World War II, my dad had worked as a trucker hauling ore down to the mill. By the time I finished high school, he had another operation mining quartzite east of Globe and trucking it to the smelter at Miami [Arizona], which needed a supply of silica. I worked with him there a couple of summers. It was about 8 miles one way. You were supposed to do five trips a day, going out and loading up the stuff yourself, taking the truck over to the smelter, and then going back and getting another load. The truck was a WWII surplus truck with a top speed of 45 miles per hour. It put out a lot of heat, so it was really unpleasant, especially in hot Arizona summers. That’s why I dreamed of getting a job somewhere cool and wet, like San Francisco. Davis is as close as I ever got, but in the end it turned out to be the ideal place for me!

TC: Why did you decide to major in geology?

EM: In high school, I didn’t know that I wanted to be a scientist; I was more interested in history and music. I was born with a fair musical talent, but this was the early 1950s, and if you were from a mining town in central Arizona, you didn’t think about going into music. By the time I had to declare a major at Caltech, I’d taken a beginning course in geology, and it seemed OK. I knew I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in a laboratory. So I selected geology.

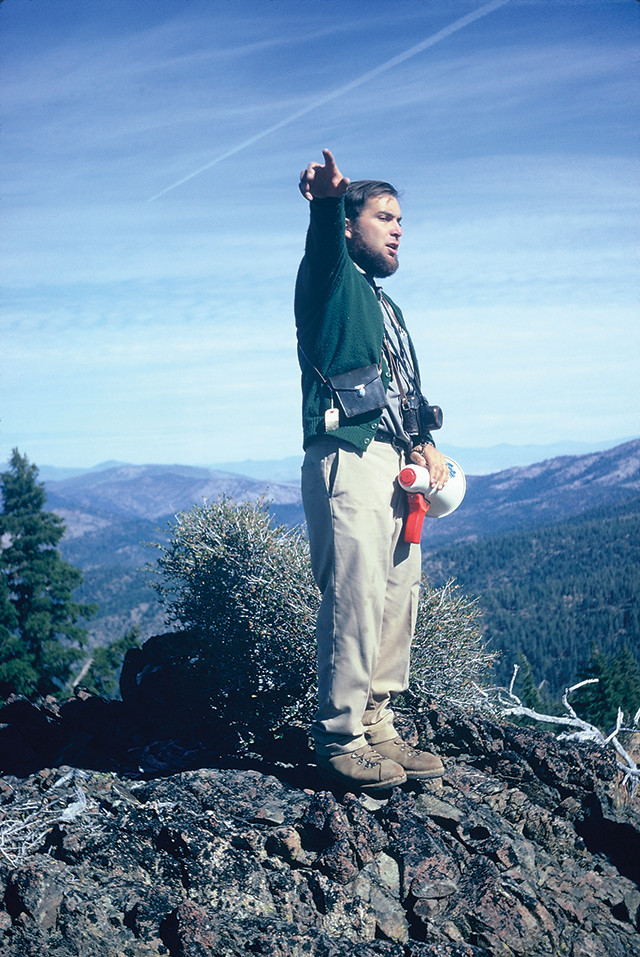

Moores co-leading a field trip on the Trinity ophiolite in the Klamath Mountains of California in August 1972. Credit: Greg Davis.

During field camp, I realized that I loved thinking about geologic structures in three dimensions. That’s when I decided that structural geology, field mapping and tectonics were what I really wanted to do. It intrigued me, because I was able to visualize structures in three dimensions easily, and it gave me a good feeling.

TC: What were some of your early mapping experiences during graduate school?

EM: At Princeton, you took classes during the first two years and worked on your thesis in the summer. If you did it right, you could get out in three years. Toward the end of my first year, two other students and I went to Hess and told him we’d like to work in the Caribbean. He knew a woman with contacts in the Haitian government, and so the three of us went there and spent two months doing reconnaissance. Hess was really interested in peridotites, but we missed them. They weren’t on the map that we had, and we didn’t see them. After two months, we had to pull out because it had become unsafe. After my mother became sick, I felt that I needed to be closer to my family, so I switched to eastern Nevada. Because that first summer [in Haiti] didn’t work out, it ultimately took me four years to finish my doctorate at Princeton. At that point, I really wanted to go abroad and see more of the world, and especially Europe. I teamed up with John Maxwell to go to Greece for my postdoctorate.

Moores and his wife, Judy, celebrating their 50th anniversary in 2015. Credit: Dan Simmons.

TC: It was during this time that you met your wife, Judy. How did that happen?

EM: I was immature and didn’t really have a social life. I’d gone to two all-male schools and then spent 14 months in northern Greece. My mother died while I was on my way to Greece, and I was really lonely and somewhat depressed. When I came home, I realized that I had to find a companion, somebody to share my life with. I met my wife on a change-partner dance at Mount Holyoke College on Dec. 5, 1964. We got engaged on New Year’s Eve and married six months to the day after we first met. We celebrated our 50th anniversary last year. My career would not have been possible had it not been for Judy — my faithful companion, manager and alter ego. I view this very much as a two-person career.

TC: When did you first realize what ophiolites are?

EM: In Greece I worked on a well-known ophiolite body trying to evaluate three separate models of their origin. I came up with a new interpretation that it was oceanic crust overlying suboceanic tectonite mantle. When I was writing up my Greek study at Princeton, Fred Vine joined the faculty. The two of us would talk about what ocean crust that had formed at a spreading center would look like. My “aha” moment came early in 1966, when I first saw a map by R.A.M. Wilson that showed the geology of the Xeros-Troodos area in Cyprus. His map showed pillow lavas and peridotites with a sea of diabase between them. I went to Fred and I said, “What about this? Does this look like ocean crust formed at a spreading center?” It took a couple of years to document things to the point where we felt we could publish it. So our first paper on the seafloor spreading structure in the ophiolite of Cyprus came out in 1971.

TC: What was it like to be part of the plate tectonics revolution?

EM: It was really exciting. There was a famous conference convened by Bill Dickinson after our second year in Cyprus. I had 20 minutes to give my first real presentation of this Troodos story, and it really hit the nail on the head. One of the things we discussed was how to apply this new idea of global tectonics, which was about modern motions, to the geologic record. There was more and more excitement as the three days of the conference wore on. On the final day, I had another “aha” moment, putting together a scenario for ophiolites and tectonic development of the western U.S. mountains. That paper came out in late 1970. The whole experience “jazzed” me for life.

TC: Fifty years hence, how has the field changed?

EM: In “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” [philosopher of science] Thomas Kuhn talks about how most scientists spend the majority of their time in what he calls the “mop-up stage,” during which the field has a reigning paradigm and everybody is filling in the gaps. When you find contradictory information, you at first put it aside, but when you end up with so much of it that you can no longer ignore it, you have a crisis. Then someone comes along and has a flash of insight and comes up with a new model that has greater explanatory power than the old one. That’s where geology was in the early part of my career. We had separate fields that all came together during this revolution. Since then, the fields have separated again. There’s been major progress in many areas. However, there is more reductionist work going on now than there was during the plate tectonics revolution. But it’s still an exciting field.

TC: What do you believe is your legacy?

EM: There are several aspects. In Nevada, my study with colleagues was one of the first to recognize low-angle normal faults in the U.S. Basin-and-Range Province, features also now recognized in ophiolites and mid-ocean spreading centers. With my new doctorate, I was lucky to be able to do fieldwork in northern Greece, which, with Vine’s and my Cyprus work, contributed to our emerging understanding of the development of oceanic crust by seafloor spreading, how ocean crust has varied through time, how it’s emplaced on land, and the tectonic significance of that emplacement — knowledge that is still regarded as foundational. I’ve worked with colleagues and students on the plate tectonic development of western North America, of northern Greece ophiolites, of Cyprus and other ophiolites around the world. Also during the early days of plate tectonics, which were incredibly exciting times for many of us, I worked together with others on continental drift, the patterns of continent assembly and fragmentation, and the evolution and fluctuation of global sea level.

At UC Davis, as professor and chair, I helped develop an internationally respected Department of Geology (now Earth and Planetary Sciences). I’m proud of the many students who have gone through this department and on to productive careers as earth scientists.

As editor of Geology, I helped build the journal into the world’s leading short-article earth science journal. As president of the Geological Society of America (GSA), I helped initiate its program of internationalization and encouraged the dissemination of geologic concepts to the public. As vice president of the International Union of Geological Sciences, I helped oversee projects around the world and integrate that body with the International Geological Congress.

Moores lecturing on the geology of the northern Sierra Nevadas to students from California State University at Chico in September 2003. Credit: Elridge Moores.

Personally, I’ve worked locally and nationally to increase public awareness of and interest in geology through publications, lectures and field trips. With the extensive knowledge of geology I have acquired over the decades, I work to practice “generativity” — imparting this knowledge to lay people and younger geoscientists. More recently, my wife Judy and I have introduced more than a thousand people to California geology through our field trips. And we raised three amazing children, and now enjoy watching our three equally amazing grandchildren as they develop their own talents.

TC: How did you encourage innovation when you were the editor of Geology?

EM: We had a motto that articles should be short, innovative, provocative and creative — and should be published quickly. We’d send one copy to an editorial board member and one to an outside reviewer. If both said to publish, then I’d take it. Occasionally, I’d get reviews where one person would say, “It’s great,” and the other would say, “No, no, never publish it.” I did publish papers like that to stir things up. These papers and others were the leaps, the new ideas I was trying to find and encourage.

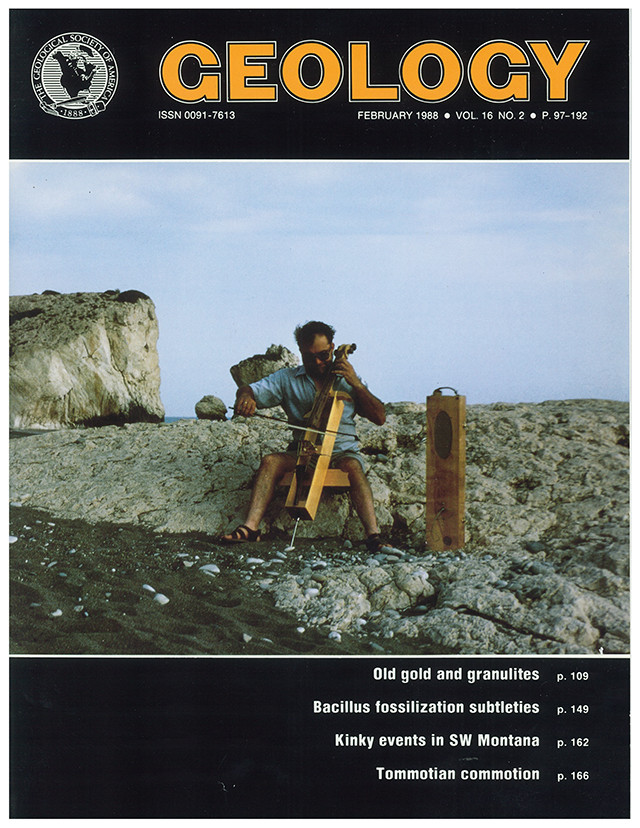

In 1988, to commemorate the end of Moores' six-year tenure as editor of Geology, editors ran a cover photo of Moores cello atop the brecciated Triassic limestone at Petra tou Romiou, Cyprus. Credit: Bob Varga/UNOCAL.

TC: What’s the story behind the cover photo on the last issue of Geology that you edited?

EM: The staff at GSA thought it would be appropriate to publish an image of me for my last issue. The photograph is of me playing a “travielo” (traveling cello) near Petra tou Romiou, the rock on the south coast of Cyprus where [in Greek mythology] Aphrodite was born out of the waves. I started playing the cello as a freshman in high school and ended up as principal cello of the Phoenix Youth Symphony. When I went to Caltech, I took my cello with me, but I rarely had an opportunity to play. As a graduate student I took piano lessons. Years later, my daughter was about 12 years old and was rapidly passing me on the piano. I didn’t want to compete with her, so I started taking cello lessons again. I still play both instruments regularly. This traveling cello was designed and built by a civil engineer in Bethesda, Maryland, and I took it as carry-on to Cyprus in the summer of 1985. A former student took the photo. I played cello in the UC Davis Symphony Orchestra for 28 years, from 1982 until 2010.

TC: Did playing the cello help you in your fieldwork?

EM: It doesn’t do any harm, and it certainly is very relaxing. I can play a scale on the cello and feel tension dissipate. Music has been an essential part of my life. When you work on a piece or a difficult passage, either on cello or piano, and all of a sudden it goes right, you get an emotional high. It’s the same feeling you acquire in science, when you achieve some real insight. I seem to have my best insights at three in the morning, which makes it hard to sleep sometimes.

TC: What has it been like working with John McPhee?

EM: It has been a rich and rewarding experience. In fall 1978, Princeton geology professor Ken Deffeyes called and asked me if I knew a New Yorker writer named McPhee: I didn’t. He explained that McPhee was doing a project on Interstate 80 and needed someone to cover California with him for a weekend. When McPhee came out, I drove his rented pickup truck. He’d be sitting on the other side with a stack of 5-by-8 notebooks, scribbling away and pelting me with questions. The first day we went up to the Auburn Dam site that he writes about in “Assembling California” [first published as a series of articles in the New Yorker and then, in 1993, as a book.] The next day we went all the way to the Nevada border and did the entire highway back to Davis. When we got to the end, I told him that I was bushed, that he’d really put me through the ringer. And he said, “How do you think I feel? This is all new to me!”

TC: How did that one weekend turn into more than a decade of collaboration?

EM: His final day here that first long weekend, we went to look at the Smartville Complex, where you can see pillow lavas and sheeted dikes. He said, “This is the clearest thing any geologist has shown me.” I told him he hadn’t seen anything until he’d seen Cyprus. So we met there for a week in 1982, and then we spent a couple of days in northern Greece. At that point he wrote everything, as I remember, five times, and it was the third revision that he sent to the scientist. I spent 10 days going through the draft of “Assembling California,” and then he came out here, and we sat down and spent 10 days going through it together. Then the Loma Prieta earthquake occurred [in 1989], and we spent several days driving the fault. He’s a wonderful fellow. He’s shy, polite, deferential, but he’s also one of the most formidable interviewers I have ever encountered. We still stay in touch.

TC: How did working with McPhee impact your career?

EM: There’s a passage in the book in which he writes about how I’ve been his counselor through all his studies in geology and our beards have grown gray together, and that’s very true. Because of McPhee’s popularity, I became somewhat famous in the public arena shortly after the book came out. It’s changed my life because he made California geology so popular that there’s a real demand for field trips, especially recreating the trips I did with him. People really do have a hunger for learning about geology.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.