by David B. Williams Tuesday, January 27, 2015

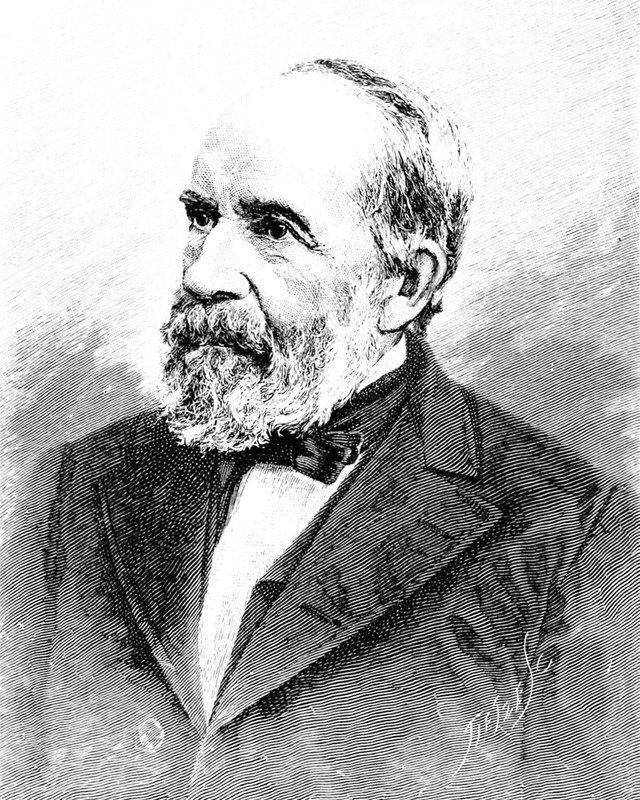

The Swindling Geologist traveled through the Midwest and Northeast in the early 1880s, impersonating famous geologist Clarence Dutton among others. The real Dutton is seen here. Credit: NOAA Photo Library.

When Clarence Dutton spoke, people listened. As one of the most famous geologists of the late 1800s, he regularly attracted large crowds to his talks. He also had a way with women. The president of an Indiana literary society once wrote to Dutton to confirm a lecture and assured the speaker that “the ladies would be delighted to see him again.”

The man many people thought was Clarence Dutton, however, was actually an imposter. Beginning in the early 1880s, this swindler traveled throughout the Midwest and Northeast pretending to be Dutton and several other famous geologists, bilking people out of cash and goods. By the time he impersonated Dutton, his exploits had made him infamous in the scientific community.

Not much is known about the Swindling Geologist, as he came to be called. His true name, place of birth, upbringing and education were never revealed. He first appeared in the news in 1884, following his arrest on Feb. 9, in Philadelphia, Pa. Pretending to be William Rush Taggart of the Ohio Geological Survey, he befriended Ferdinand V. Hayden of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), stole one of Hayden’s rare books and made off with $20. It’s hard to understand how Hayden could have been duped by the Swindler, as he had once written a formal commendation of the real Taggart after employing him on his 1871-72 survey of Yellowstone.

In fact, this wasn’t the first time the Swindler cheated Hayden. Just four months earlier, the Swindler had visited Hayden disguised not as the clean-shaven, mid-20s Taggart, but, with black whiskers, as the middle-aged T.S. Holmes of South Carolina. After dining together, the Swindler borrowed money from Hayden, claiming he needed cash for a train he had to catch immediately.

Hayden eventually caught on to the Swindler’s ruse, learning through correspondence that the imposter had not only posed as Taggart and Holmes, but also E.P. Strong of the Kansas Pacific Railway, E. Douglas of the Ohio State Geological Survey and E.D. Whitney, a geologist from Denver. Under these and other aliases, the Swindler had defrauded people from Ohio to New York, taking hundreds of dollars as well as acquiring fossils, minerals, Indian relics, rare books and scientific instruments.

Hoping to alert others to the Swindler, Hayden sent letters to the journals Science and American Naturalist. Hayden noted that the Swindler “was heavy set, shabbily dressed and with rather deep set eyes.” He went on to say the imposter “talked glibly about fossils … [and] had an adroit way of ingratiating himself into the confidence of his intended victims.” Hayden sought any information on the Swindler’s real name and whereabouts, though he neglected to say that he himself had been victimized.

It is unclear what effect Hayden’s letters had, but the Swindler disappeared from the news until Aug. 6, 1885, when he resurfaced in Davenport, Iowa. Now he was 36-year-old Francis Arandel, a native of Austria and a fourth-generation geologist (and probably not a real person). According to his fake bio, his father, grandfather and great-grandfather had chaired the geology department of the University of Prague since 1792. During his stay in Davenport, the Swindler visited the local college and helped classify and label more than 120 fern fossils. He also promised to return soon and donate additional specimens and books — in return for ones the college had given him.

As one of his later personas, the Swindling Geologist morphed into the namesake son of Leo Lesquereux, a well-known, Swiss-born, deaf paleobotanist who had settled in Ohio. The real Lesquereux is pictured here. Credit: U.S. public domain.

A week later, and about a hundred kilometers to the north in Monticello, he morphed into Fred A. Arendel, principal of the Ohio State Deaf and Dumb Asylum (likely not a real person either). Still claiming to be a geologist specializing in plant fossils, he now claimed his new place of birth was Germany and he was a deaf mute who only corresponded by pen and paper. Though he would pretend to be deaf and dumb later in his career as well, the Swindler abandoned this ruse and became the namesake son of Leo Lesquereux, a well-known, Swiss-born paleobotanist who had settled in Ohio. Deaf from an illness in his early 20s, the real Lesquereux could lip read and speak French, German and English.

Traveling throughout Minnesota and Wisconsin from July to October 1885, “Lesquereux Jr.” continued to snooker the unsuspecting. In one town, he used a mysterious formula to show two mine owners the “unexcelled richness” of their ores, for which he was paid royally, honored and feasted. In another town, he borrowed books from one person, sold them to a second, then borrowed them back and returned them to the original owner. And always, he appropriated specimens and scientific equipment and bailed on his lodging charges.

Each town also brought a slight change of persona, as if he were testing his victims to see how much he could get away with. He claimed to have broken both legs and an arm while on Maj. John Wesley Powell’s historic 1869 exploration of the Grand Canyon. He claimed he had lost his left arm and had an artificial hand. He claimed he was French.

His luck ran dry, however, in Whitewater, Wis., home of the Whitewater Normal School, now the University of Wisconsin at Whitewater. As Lesquereux Jr., the Swindler claimed to represent the USGS for the purpose of loaning the school a collection of 4,000 fossils from the Smithsonian Institution. The collection would arrive soon, he said; but before it did, the Swindler borrowed several valuable books from William F. Bundy, professor of science at the university, and then skipped town. Bundy tracked the Swindler to Milwaukee, 80 kilometers east, where the Swindler was working at the Milwaukee Public Museum. He had also sold Bundy’s books, which led Bundy to contact the police.

Placed under arrest, the Swindler was charged with receiving stolen property. Of course, he said, he was innocent; someone must be acting as an imposter and smearing his good name. Brought back to Whitewater, the Swindler eventually pleaded guilty and received three months in the county jail at Elkhorn.

The only evidence of the Swindler’s handwriting comes from his time at Elkhorn. On Dec. 10, 1885, he wrote in precise script to Carl Doerflinger, custodian of the Milwaukee museum, thanking him for sending $5 as a loan. The Swindler remarked that Doerflinger’s note and one other were “the only kind words received since my arrest.” He signed the letter as either Leo Lesquereux Jr. or F.A. Arendto (it is hard to tell).

By March 1886, the Swindler was out of prison and had returned to his previous ways. As Professor Henry Shaler Williams of Cornell University, he identified fossils, borrowed money and led geologic tours throughout Iowa. In St. Cloud, Minn., he was Capt. Israel C. White, which prompted the real White to alert the readers of Science. “Cannot something be done to throttle this nuisance before he scandalizes every geologist in the country?”

White got his wish. In July, the Swindler was arrested in Champaign, Ill., while acting as Capt. Roy M. Lindley of the U.S. Army. Sentenced to jail in Kankakee, the Swindler said he hoped to reform and told a reporter that he “never stole anything for the profit there was in it, but because in the presence of rare geologic specimens or works he experiences an overmastering desire to possess himself of them.”

Out of jail by November, the Swindler became Charles Walcott and took a new tack: writing letters seeking the donation of reports and books. Perhaps this route didn’t meet with success, leading him to his short career as Clarence Dutton, followed by Ivan C. Vassile, a deaf mute from Russia; Dr. S.M. Gutmann, a chemist from Germany; Louis P. Gratacap of the American Museum of Natural History; and Otto Syrski, also a deaf mute from Russia.

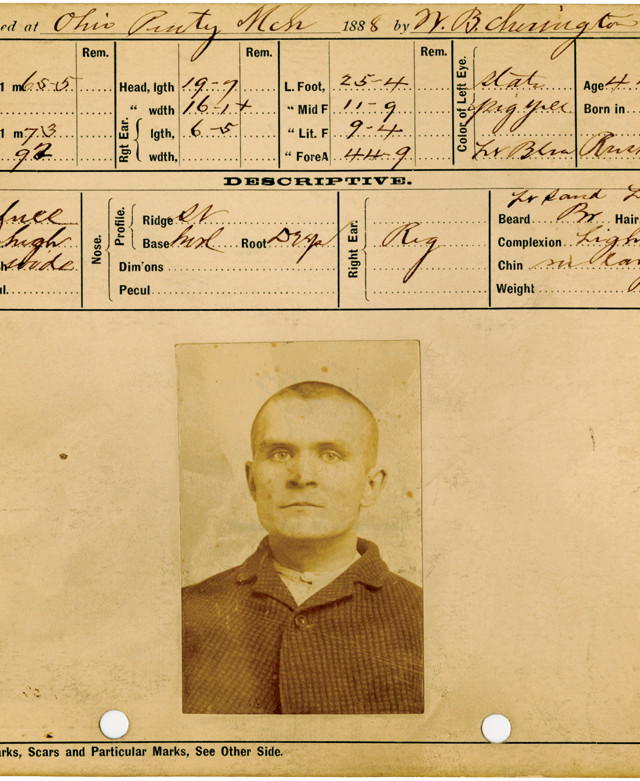

It was as Syrski that he served his longest prison term. After he stole several microscopes from the University of Cincinnati in January 1888, city detectives telegraphed out a warrant for his arrest. Tracked through Kentucky and Indiana, the Swindler was arrested in Nashville, Tenn., and returned to Ohio, where he pleaded guilty to grand larceny.

The Swindling Geologist was arrested and sent to prison multiple times — as different people, of course. The third time he was arrested and imprisoned in Ohio as Otto Syrski, a deaf mute mining engineer from Russia. He was paroled after two years. Despite having this mug shot and arrest record of the imposter, police never learned his true identity. Credit: Ohio Historical Society.

Prisoner number 19449 entered the Ohio state penitentiary in Columbus on March 5, 1888, to serve a five-year sentence. The authorities must have considered his crime serious, as another prisoner convicted of grand larceny received just 18 months and another convicted of second-degree murder also got five years. While in prison under the name of Syrski, he was a model prisoner who taught a group of Apache Indians to speak English.

After just two years in prison, he was paroled on June 9, 1890, and became Otto Ludovitz Sassulich, brother of the famous Marxist and revolutionary, Vera Sassulich. His last known appearance was in Columbia, Mo., in June 1891. Returning to his deaf and dumb ploy, he attempted to fool Garland C. Broadhead, a professor at the local university, but Broadhead recognized him as the Swindler and hurried him off. The Swindler, Broadhead wrote in a letter to American Geologist, was “very gifted and smart, and is well posted in paleontology, and would make the best [geologist] I have ever known provided he stuck to it and honesty.”

The Swindler then vanishes from the written record.

In a 1994 article in the journal Isis, Daniel Goldstein, now a social sciences and humanities librarian at the University of California at Davis, points out that a network of amateur naturalists existed in the United States at the end of the 19th century. These men and women kept up on scientific developments, knew the names of important researchers and carried on extensive correspondences with established scientists at impressive institutions such as the Smithsonian. These swindlers succeeded in part by trading illicitly on the “depth of their dedication to what they regarded as civilized life,” Goldstein writes.

This is certainly evident in the newspaper accounts of the Swindling Geologist. Whenever he arrived in town, the local paper would gush, citing his credentials and how he generously helped classify and label specimens. Within a few days, however, the paper would follow up, crestfallen at the ruse. The Advance Sun, of Redwing, Minn., described him in October 1885:“He is really a rara avis. It would seem as though science must be at a discount, when so learned an expert adopts such a life. He ought to be caught and kept in a museum as a study for anthropologists, psycologists (sic), and students of moral insanity.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.