by Lucas Joel Thursday, November 12, 2015

Nigel Hughes in Bengal. Credit: Nigel Hughes.

I first met Nigel Hughes, a paleobiologist at the University of California at Riverside (UCR), in 2010. He took me on a brisk walk through the UCR Botanical Gardens, where the trees kept us cool in the hot Southern California sun while he told me all about trilobites.

When I later spoke with Hughes for this interview, I learned that walking and hiking in nature with his family when he was a child is what first sparked his interest in science, and ultimately, in paleontology.

Since those early days of exploration, Hughes has walked through the Himalayan region — from Nepal to Tibet — looking for trilobites that might help him reconstruct when and how these mountains formed. Before completing his doctorate at the University of Bristol in England, he walked and biked the streets of a small village in West Bengal, India, where he lived for a year. His time there offered inspiration for a children’s book he later wrote, titled “Monisha and the Stone Forest,” about a young Bengali village girl who interprets the natural history of the fossils near her home. The village where Hughes lived is also where he learned to play the ukulele, which he continues to do today, often while singing about trilobites.

The remoteness of deep time, and how Earth has changed through geologic history, has long drawn Hughes to his research. For him, a Sanskrit passage encapsulates the essence of fossils well: “It stirs and it stirs not, it is far, and likewise near.”

Hughes at an outreach program in Tangail, Bangladesh. Credit: Nigel Hughes.

LJ: How did you get into paleontology?

NH: I went to a Quaker school in England that has the oldest school-based natural history society in the world, and when I enrolled I immediately became a member of that society. I learned all sorts of things about natural history, astronomy, ornithology and nature in general, and I was interested in all of it. I also had a natural interest in geology.

LJ: How did that interest start?

NH: To send my brother and me to school, my parents saved all their money, and they didn’t have much to spare. When we went on holiday, we did one thing: walk. We didn’t go to expensive hotels or do anything else. My parents sacrificed that way. We walked — and hiked — usually in mountainous areas, and that was great for becoming interested in rocks. There were lots of kids who were interested in birds, and I thought: “Well, if I’m going to be knowledgeable about something, I want to know about something that no one else is knowledgeable about.” [Laughs.]

When I was 9 years old, I saw a NOVA program on plate tectonics, which was a new theory at that time in the 1970s. [I was amazed] that Earth appears so stable in our own lifetimes, but over millions of years it changes. It’s a beautiful combination of different data coming together to be explained by a common framework. My brother, Simon, who’s five years older and who’s a developmental biologist, was a big influence too.

Hughes shares a laugh with Bipod Tarun Das Baul, a folk singer who is featured in the book "Monisha and the Stone Forest." Credit: Nigel Hughes.

LJ: How did fossils and trilobites come into your life?

NH: I was first drawn to geology through volcanoes and plate tectonics. I did not think about paleontology until high school when I went to a paleobotany lecture. It was striking to me that you could have the Carboniferous world, for example, with very different geographies and also very different ecosystems of forests from those we know today. It was then that I started to think about distributions of fossils as an independent data source for plate tectonics.

As for trilobites, it wasn’t like I was a trilobite nut. I was interested in ancient life and in the ancient worlds, and it just so happened that the particular project I was selected for by my doctoral advisor, Derek Briggs, dealt with trilobites.

LJ: How did you become involved with research in India?

NH: My Quaker school was very focused on social justice, and I was involved in a refugee project dealing with displaced people in Bangladesh. I became fascinated with the region. Later, before starting my doctoral work, I took a year off and I went to college in India at a university in West Bengal founded by Rabindranath Tagore, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. It was a magnificent experience for me. That’s where I started to play the ukulele. Each college, at the start of the academic year, had an introductory entertainment evening. I found myself on stage in front of about 500 people having to sing.

Hughes talks with a class for girls at Erlanger in Bangladesh. Credit: Nigel Hughes.

LJ: When did you start working in the Himalayan region?

NH: My postdoctoral research was the first time I worked in India, where I did classical descriptive paleontology of Cambrian trilobites, but with the purpose of better understanding Himalayan structure and history. I’ve always tried to balance my work such that it has evolutionary, biological and geological implications. I don’t love the specimens for themselves. I like them and I admire them very much, but I want to apply them to something that is of broader importance.

We’ve worked all along the Himalayan margin — the Ladakh and Spiti regions of India, Nepal, Bhutan and Tibet, and even farther afield — trying to reconstruct Cambrian history along the margin and along the tectonic belts of the Himalaya. If we want to understand what the margin was like prior to India colliding with Asia, the Cambrian is a good time to study because there is a widespread set of rocks of that age that are preserved in different Himalayan tectonic zones.

Hughes and colleague Paul Myrow doing fieldwork in the Kumaon region of India. Credit: Nigel Hughes.

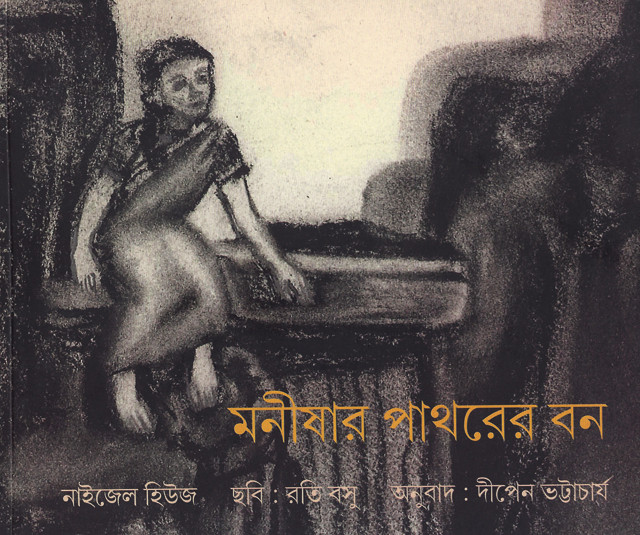

This is the cover image of the children's book Hughes wrote, entitled "Monisha and the Stone Forest." Credit: Nigel Hughes.

LJ: What have been some of the biggest realizations or discoveries from your work?

NH: We’re almost done setting up the primary Cambrian biostratigraphic zonation of the Himalaya. There are very few regions of the world now where it’s possible to still do that, and it’s quite fundamental. We can then use this framework for testing understanding of collisional tectonics, so the pleasure of our work has been to apply the knowledge that we have on the depositional ages of the rocks to different tectonic zones. If we want to compare, say, the geochemical characterization of the rocks, it’s really important to have independent evidence of when the rocks being compared were deposited. And if we have confidence that the ages of the rocks that are being compared are similar, something significant is necessary to explain observed geochemical differences. We have been able to assess whether parts of the Himalaya are all part of the same tectonic unit in the Cambrian, or whether some had different regional histories.

Based on this understanding, our group has recently suggested that uplift south of the Main Central Thrust began about 16 million years ago, 5 million years earlier than commonly assumed. This has important implications for understanding changes in global seawater chemistry that occurred at that time. My former student Ryan McKenzie, now a postdoctoral researcher at Yale University, has done a great deal of important work using detrital zircon dating in the northern Indian margin, and has recently recognized intimate connections between global Late Cambrian volcanism and the Earth-life system.

__ LJ: You wrote a children’s book in Bengali about fossils. How did that come about?__

__ NH:__ The Geological Society of India has an outreach mission for kids, and they wanted to publish books on geological topics in regional languages — India of course has many such languages. I thought that would be a very exciting project. When I was going back to Kolkata to see my friends from college, it occurred to me that India was the only place I could write about because I knew the people well, and had spent a lot of time in villages and I knew something of local customs. I wanted the book to be about a child from a village background, and not somebody who was privileged in their education.

The girl in the story, Monisha, seeks a natural explanation for strange material that is naturally common in the region: petrified wood. This stuff is odd — it looks like one thing (wood) but is clearly another (stone) and thus has attracted various supernatural explanations in the different local religious traditions. In the story, Monisha, through a series of adventures involving finding new material in situ and a visit to some hot springs, discovers for herself the natural explanation for how this material formed. She does so without any received knowledge of geology: She doesn’t read a book, or have a teacher explain things to her. Rather, she works out the explanation from first principles. She’s an extraordinary girl, but she makes observations and conclusions that anybody could make. For this she’s rewarded with a fever-induced trip back into the Miocene-Pliocene boundary, where she sees the animals that were alive then, which introduces kids to evolution and global change in a local context.

LJ: Will there be another book?

NH: For our next outreach project to local kids, I’d like to do something a little bit more related to the Himalaya, trilobites and Mount Everest — more related to our actual research. But this first book was a lovely way for me to bring together the different parts of the fortunate experience that I’ve had.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.