by Lucas Joel Wednesday, February 13, 2019

Lindsay Hunter finds a perch in the Rising Star Cave in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage site in South Africa, where she helped excavate the bones of Homo naledi. Over three weeks in November 2013, Hunter and her colleagues excavated more than 1,500 fossil pieces from specimens of the previously unknown hominin species. Credit: ©Wits University/Elen Feuerriegel.

In 2013, Lindsay Hunter found herself at a personal and professional crossroads. She had gone through a divorce, left the paleoanthropology doctoral program at the University of Iowa, where she had received her master’s in 2004, and moved, along with her three dogs and two cats, to live with her parents on a farm outside Austin, Texas.

Hunter picked up some freelance writing work, but the farm lacked reliable internet access, so she often worked at a nearby coffee shop. Late one night at the coffee shop, she happened upon a Facebook post uploaded by Lee Berger, the paleoanthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa who had discovered Australopithecus sediba in 2008. Berger was looking for team members for an upcoming expedition. His message read:

“We need perhaps three or four individuals with excellent archaeological/paleontological and excavation skills for a short-term project that may kick off as early as Nov. 1, 2013, and last the month if all logistics go as planned. The catch is this — the person must be skinny and preferably small. They must not be claustrophobic, they must be fit, they must have some caving experience; climbing experience would be a bonus."

The message was cryptic, but Hunter was intrigued enough to apply. Within a few weeks she found herself in South Africa, one of six members of a highly specialized team of scientists whom Berger dubbed “underground astronauts.” Instead of rocketing into space, however, she and her fellow explorers dove into the remote recesses of the Rising Star Cave near South Africa’s Cradle of Humankind World Heritage site, which is riddled with limestone caves that have produced some of the greatest fossil hominin discoveries.

The mission was to excavate skeletons of the species that would come to be known as Homo naledi — the most complete fossil hominin skeletons ever discovered. While there she also met her now-husband, Rick Hunter, who was one of the two recreational cavers who first discovered the H. naledi remains.

Today, she lives and works in South Africa, where she helms a National Geographic-funded outreach program called Umsuka, a public paleoanthropology outreach program that helps South Africans learn more about the fossil heritage in their own backyard.

It was at the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage site in January 2018 that I met Hunter and spoke with her for EARTH about her journey, the sometimes-harrowing trek inside the cave and the importance of science outreach in South Africa.

LJ: Where did you grow up?

LH: I’m originally from St. Louis, and my undergraduate education was at the University of Missouri, St. Louis. I would’ve been the first in my immediate family to graduate from college, except that my mother actually graduated from the same college a semester ahead of me. I studied history, and my minor was in anthropology.

LJ: What were the questions behind your doctoral research at the University of Iowa?

LH: I was looking at trying to create a baseline for thoracic shape in lung capacity in later Homo. That included Neanderthals and more recent modern humans. Did Neanderthals have a greater lung capacity? Did they have this barrel-shaped rib cage that they’re often purported to have had?

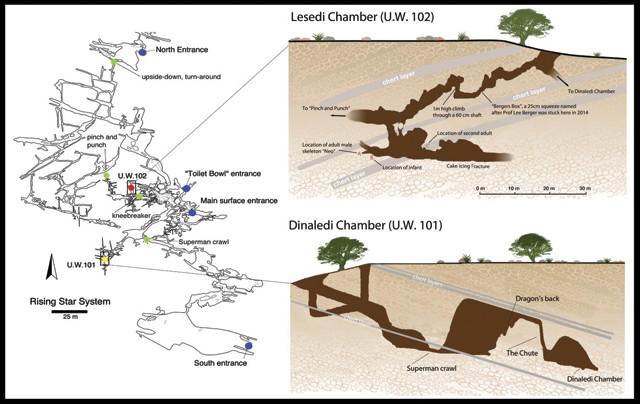

Schematic of the Rising Star Cave system. Credit: ©Wits University/Marina Elliott.

LJ: What did you think when you first saw the unusual ad posting for the Rising Star expedition?

LH: I was just like “Hmm.” It was the middle of the night, so I was probably one of the first people in the U.S. who saw it, because he’s posting it in South Africa. For me it was like the [Ernest] Shackleton ad: “Men wanted. Safe return uncertain, but in case of success, fame is guaranteed.” It was just so enigmatic. “Skinny scientists who are not claustrophobic,” and I was like: “What could this be?”

When I got the email back that I’d been chosen for an interview, I felt sick. I remember refreshing it, and refreshing it, and refreshing it, and printing the response that they wanted to meet with me over Skype, and I was like “Oh my God, this isn’t true.” Then I heard back that they’d like to have me, and I was screaming all around the farm.

LJ: Did you have any caving experience?

LH: I had been in caves, but I didn’t realize that caving was a thing. I like squeezes and I’m not claustrophobic, but I did not have proper spelunking experience. I did have some basic rock-climbing experience. In my cover letter, I emphasized that I have a lot of flexibility and that I’m very athletic, and that I pick up things very quickly. I actually trained and competed in Olympic modern pentathlon, and at the time that I applied for the Rising Star expedition, I was training for a roller derby. I told them: I have the academic chops. Physically I can do this. I don’t do this every day, but you throw me in and I can do it.

LJ: When you realized what you would be doing in the expedition, were you fazed at all?

LH: No, I was super stoked. What I like about caving is the three-dimensional part. I love using my whole body, where you’re like ‘I’m using my cheek to get up here!’ I really loved how it was full contact.

LJ: What was it like to go into the cave, and get into the Dinaledi Chamber where the fossils were?

LH: From the cave entrance, it’s about 80 meters into the dark zone before you get to a chute leading to the bones. You go down the walk-in entrance, which is a slope with a drop-off to the left-hand side. Then you duck into a small chamber and on the right-hand side there’s an open chamber that has an installed light; and there are a lot of porcupine nests and porcupine fleas. You don’t want to spend too much time in that little chamber.

They [the Rising Star team] put in a rope line that you could follow like bread crumbs. You sort of slope down, and there are some ladders, and some sideways squeezes and things, and when you get to the Superman Crawl — where you have to have one arm in front and one arm in back as you squeeze through — that’s when you’re getting into the meat of things.

Hunter was one of six scientists specially selected for their knowledge of paleoanthropological and archaeological fossil excavation techniques, their caving and climbing skills, and their small physiques, which helped them navigate passageways as narrow as 19 centimeters wide to reach the bone chamber. From left to right: Becca Peixotto, Alia Gurtov, Elen Feuerriegel, Marina Elliott, Lindsay Hunter and Hannah Morris. Credit: ©Wits University/John Hawks.

LJ: How did you feel the first time you went through the Superman Crawl?

LH: It was fun, but a little bit disconcerting because, the first time, you don’t know how long this is going to go on. So you’re like: “I’m fine, I’m fine, I’m fine. When is this over?” Once you have a good gauge on how long it is, you’re fine.

LJ: From there, how do you get to the chamber where the bones were found?

LH: After the crawl, you come out into the Dragon’s Back Chamber, which is pretty cool. It has this large roof section that collapsed sometime in the distant past, and which resembles the back of a dragon where you climb up its spines up toward its head. So, as we were going along its spine, we would take a harness and rope in and climb along the little ledge next to it. Then you get to the top and you have to climb onto the Dragon’s Back, and there’s a gap with a little precipice on the other side. But there’s nothing to hold on to, so you need to just jump over the [about 1-meter-wide] gap — and that was the one part where we were all like, “Ehhhh.” You’d fall about 12 to 20 meters if you didn’t clear the gap.

Then there’s a small little labyrinth of formations that you go into, and there’s another little gap, and then a crevasse that has the chute [that leads into Dinaledi Chamber] down at the bottom. We had one accident there when Alia [Gurtov] slipped: I was beneath her and was going to pass a bag up; she was going up the chute but then suddenly she was coming back down the chute really fast. She got caught on a rock and banged her shin on it. We were trying to decide: Should she go up or should she come down? She was feeling pretty sick, probably from shock, and she decided she wanted to come down. She needed stitches. It wasn’t like she was going to die from it, but it wasn’t good.

LJ: How important of an experience was the Rising Star expedition for you?

LH: At the time it felt really, really big, because I felt like my life was falling apart. I had just moved to Austin at the end of August. And soon after that, this materializes. And in November of that year, I’m suddenly in South Africa doing this incredible work.

I remember one big moment for me was before I went down into the chamber, and we had the first digital scans [of the bones in situ made by a small handheld scanner] come up, and we were looking at them. I see it, and I start bawling, which you can see in the National Geographic/NOVA documentary “Dawn of Humanity.” It’s funny, anytime there was an over-the-top moment in the documentary, it was me.

LJ: What have you been working on since the expedition?

LH: I’ve been doing a lot of outreach and interpretation with NatGeo Umsuka, a public paleoanthropology outreach program that I developed. The project’s aim is to increase accessibility of our fossil hominin heritage to under-represented and underprivileged people within South Africa. The flagship program within it is the Cradle Ambassadors. This gives people who work here in hospitality and service a background into why tourists come here. But more than that, it connects them to one another, creates a network of individuals within the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage site to create community, because a lot of the people who work in this area come from vulnerable communities — for example, they’re often migrant workers or immigrants. There’s no public transportation in the Cradle, and so for the jobs here, you usually have to live on site or you have to walk an extreme distance; so these jobs end up getting filled by people who are really vulnerable, and they may not have a support structure in this area. We’re looking at ways that we can connect people who feel disconnected, so that they are able to feel ownership of this area, to take care of it and feel valued themselves.

I’ve also started work part-time on a new doctoral project, studying the structure of scientific collaboration within paleoanthropology with respect to scarce fossil remains and the consequences of that. I’m interested in how scientists organize themselves around very scarce data, how they open it or keep it closed, and how they’re able to block one another and control interpretations of the human fossil record.

The Dinaledi chamber in Rising Star Cave is the richest hominin fossil site ever discovered. Researchers recovered bones from more than 15 Homo naledi skeletons, ranging in age from infant to elderly, which are the most complete hominin skeletons ever found. Credit: ©Wits University.

LJ: Looking back, has there been a core theme in your life’s journey so far?

LH: I think it’s being able to cast yourself as the hero in your own narrative. Recognizing that you are able to control how your story ends. That events and things may happen to you, and you may not have any control over those, but you do have control over how you respond to them. You can take control so that your life’s story makes sense in the way that you want it to. That’s one thing that I’ve always found very cool about people — we’re meaning-makers. We’re sense-makers. We create our world.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.