by Terri Cook Tuesday, April 10, 2018

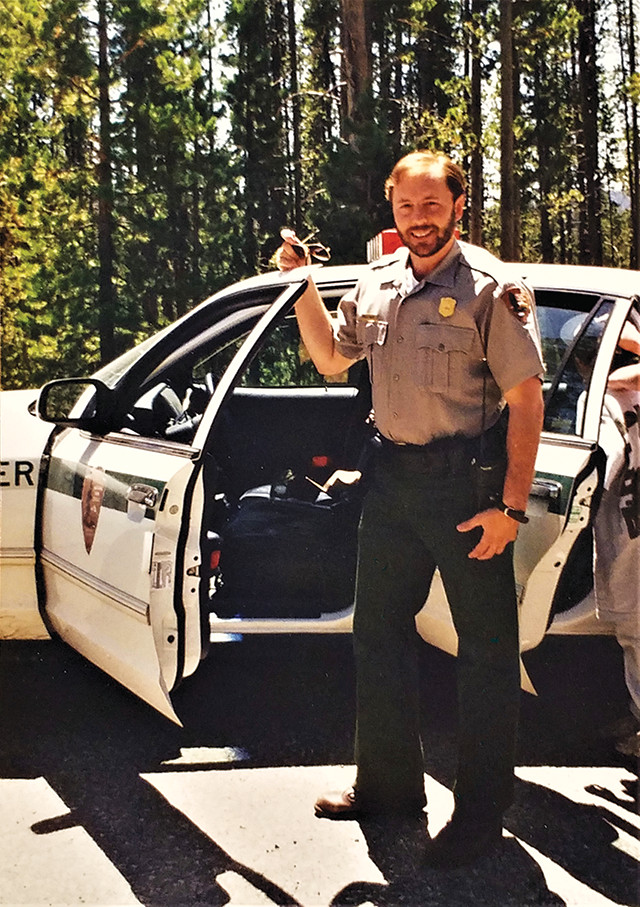

Vincent Santucci is the senior paleontologist and paleontology program coordinator at the National Park Service. Credit: NPS photo.

When Vincent Santucci was hired in 1985 to work as a seasonal ranger in South Dakota’s Badlands National Park, he assumed the most formative part of the experience would be sharing his unbridled enthusiasm for fossils with park visitors. But as Santucci explored the colorful badlands on his days off, he sometimes stumbled across people who were illegally collecting fossils. Following the first of these encounters, Santucci raced back to headquarters to report the illicit activity with the expectation that the chief ranger would rush out and arrest the perpetrator. Much to Santucci’s surprise, the ranger instead put a hand on his shoulder and drawled, “You ain’t from around here, are you, boy?” After several repeat episodes, Santucci learned that when rangers had previously caught illegal collectors and brought them before the local magistrate, the judge had refused to prosecute, citing a lack of fencing or signage that clearly informed the fossil hunters they’d been on federal land.

Later that same season, on a day that Santucci describes as the most significant in determining his career path, the young ranger discovered two men engaged in suspicious “shopping behavior” in a very remote area of the park. Although one evaded contact with him, the other — a friendly, grandfatherly gentleman — greeted Santucci, who was dressed in plain clothes, and asked if he was having any luck finding fossils. In the course of their conversation, Santucci learned that, although the man realized he was in a national park and understood that it was illegal to collect fossils there, he had done so for 25 years — and, in the process, become very wealthy. In the man’s mind, he was “rescuing” fossils that the park service would otherwise have allowed to erode away.

After the thief invited Santucci to a campsite to purchase some of his many finds, the young ranger sped back to the office to report the incident to the chief ranger, all the while bracing to once again hear the senior officer’s tired line. This time, however, the chief ranger realized that Santucci had encountered a seasoned professional and decided to mount a response.

Santucci began working undercover, eventually gathering enough information to have the man arrested. When the thief was brought before the magistrate and confessed his crimes, the judge couldn’t simply dismiss the case as he had done before. Instead, the judge fined him $50 and sent him on his way. Santucci was shocked by this outcome, and the events helped him realize that there was a much-needed role within the National Park Service for someone who focused on protecting paleontological resources.

Once the season was over, Santucci returned to the University of Pittsburgh to complete his master’s degree and also earn a law enforcement commission. Santucci has since worked as the federal government’s only sidearm-carrying paleontologist, helping protect our nation’s fossil resources while stationed at six different national parks over the years. Today, he serves as the senior paleontologist and paleontology program coordinator at the Washington, D.C., headquarters of the National Park Service. He is the author of more than 180 publications and the recipient of numerous distinctions, including the George Wright Society Natural Resource Achievement Award and the George and Helen Hartzog Stewardship Award. Much to Santucci’s delight, two fossil discoveries — Androcycas santuccii and Sapelnikoviella santuccii — have been named in his honor.

Santucci recently spoke with EARTH about the importance of fossils early in our nation’s history, the most forgotten national monument and why he has the world’s best job.

Santucci published Yellowstone National Park's first paleontological inventory in 1998. Credit: Bianca Santucci.

TC: What do you think has been the most noteworthy fossil discovery in the U.S.?

VS: If I had to name one, it’d be the original T. rex found in Montana’s Hell Creek Formation in 1902. That was the first one assigned the name Tyrannosaurus rex, and it was a really impressive specimen that captured a lot of media attention and sparked the public’s imagination about this ancient world and the organisms that lived there. The fossil is also important to me personally because as a kid growing up in Pittsburgh, I spent rainy days running around the Carnegie Museum of Natural History Dinosaur Hall, where that fossil was displayed. I naturally gravitated toward the skeleton and the life-sized T. rex painting that hung behind it. For many visitors, that was the focal point of the museum, like Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park.

TC: What ignited your interest in science?____

VS: During my childhood, my family was big on travel and camping and education, so we visited national parks all over the country. When I was 13, my uncle and I drove cross-country in a little Volkswagen Beetle. After we pulled into Badlands National Park and read that it preserves one of the world’s richest deposits of fossilized mammals, we decided to hike the Fossil Exhibit Trail, where I saw my first fossil in the wild. It was a section of jaw with teeth sticking out of it. Even I could clearly tell that those were teeth! Seeing a skeleton in a museum is one thing, but observing fossils in a natural setting within a geologic context gives it a deeper meaning. It was very exciting to think about the possibilities of what was preserved in those rocks. That experience turned me on to geology and paleontology.

TC: How have you shared your enthusiasm with others?____

VS: While working on my master’s thesis, I was very fortunate to land a seasonal ranger position at Badlands. It was a real honor to wear the uniform and learn how the park service provides public education and outreach. I was able to take visitors on hikes into the badlands and share with them my experience of seeing a fossil outdoors for the first time, and also help them find fossils on their own. No matter how common or rare those specimens were, those individuals were excited, and I found it very rewarding to share this sense of discovery with them.

VS: I have the best job in the world. It encompasses all aspects of the management, protection, interpretation, scientific study and curation of fossils, so on any given day I’m dealing with a wide variety of issues. Our nation has an incredibly rich fossil legacy, but these are nonrenewable resources, so we need to be responsible stewards. No more T. rexes are being made, and there are only so many out there beneath the ground, eroding at the surface, or in collections, so the way that we manage them should be very different from how we manage grizzly bears and redwood trees and grasslands.

TC: In 1957, a fossil site in South Dakota — Fossil Cycad National Monument — was abolished. What lessons have we learned from that?____

VS: It’s a very unfortunate story of paleontological resource mismanagement. Cycads look sort of like pineapples with beautiful fronds on top. The site in the southern Black Hills preserved the remains of very large cycads that existed during the time of the dinosaurs. Paleobotanists were amazed by the quality of the preservation; they could make thin sections and observe cellular structure and other features that had never before been seen in the fossil record. But the park service didn’t do much with the monument after it was established in 1922, and visitors eventually pocketed so many of the fossils that the site was completely denuded. Without fossils there was no longer a reason for the monument to exist, so Congress voted to abolish it in 1957. I think it is a compelling story that sends a strong message about the importance of responsible stewardship of nonrenewable fossils.

TC: How did you learn about the former national monument?____

VS: I first saw a reference to Fossil Cycad when I was working at Badlands in the 1980s. I asked around, but very few people knew about the site; it seemed like it had been almost completely forgotten. I began to do some research and over the last 35 years I’ve accumulated quite a bit of historical information. When I worked at Petrified Forest [National Park], one of the issues I was trying to deal with was illegal souvenir collecting of petrified wood by park visitors. I began using the Fossil Cycad story to demonstrate that there are localities that have disappeared because of uncontrolled collecting.

TC: You began your career in the field. How do you remain inspired now that you’re in an administrative role?____

VS: We have only scratched the surface in terms of what we know about the history of life. From my 35 years of working in paleontology, I strongly believe that most of what is to be learned about the history of life is yet to be discovered. For example, in 2012, the National Park Service completed a 10-year inventory of fossils throughout the entire park system. Seventeen units were established to protect paleontology resources, but through this inventory we identified 267 that host pieces of our country’s paleontological heritage. Together, these tell quite a comprehensive story of the evolution of life over more than a billion years, from the early Paleozoic marine invertebrates of Death Valley National Park to the Mesozoic dinosaurs of Dinosaur National Monument to the ice-age fossils of Grand Canyon National Park.

Santucci stands in front of the John Wesley Powell Fossil Track Block, discovered in 2009 in the Lower Jurassic Navajo Sandstone in Glen Canyon Recreation Area. The trackway pushed back the record of ornithopods in North America by 20 million to 25 million years. Credit: NPS photo.

VS: When we began to research the Colonial National Historical Park near Norfolk, Va., which includes the early European settlement of Jamestown, park officials didn’t think that there were any fossils there. When we began to research the area, we learned that many European cartographers who mapped the surrounding shoreline in the 1600s were based there and often earned additional money by collecting curios and taking them back to Europe to sell to private collectors. Some of these ended up in European museums, and one, a little bivalve pecten specimen, was described in an article published in the late 1600s. Everyone seems to agree that this is not only the first fossil specimen from [land that would become] a U.S. national park, but also the first fossil from the Western Hemisphere to be described and published. It was formally named Chesapecten jeffersonius and is now Virginia’s state fossil. It’s a really cool story.

VS: Thomas Jefferson and some of his contemporaries had a real fascination with mammoths and mastodons; Jefferson had mammoth remains displayed in the main den in his home at Monticello. He was optimistic that Lewis and Clark would encounter a live mammoth or mastodon as they journeyed west for the first time, and he instructed them to be on the lookout. There are many other examples as well. In Gettysburg, there’s a stone bridge that was constructed near the battlefield in the 1930s. During the quarrying operation [to collect stone for the bridge], workers discovered dinosaur footprints from the Triassic in the stone. So, long before Union and Confederate soldiers marched across the battlefield at Gettysburg, dinosaurs left their footprints in the mud there.

TC: Since your time at Badlands, have any new laws been passed to better protect America’s fossil legacy?____

VS: Badlands was a real center of activity because of how valuable these fossil mammals were and how little preparation they needed. The legal battle and eventual sale of Sue the T. rex for $8.5 million in 1997 showed that there was a very strong commercial market for fossils, and it demonstrated the need for protective legislation. It took a long time, but finally, in 2009, President Obama signed the Paleontological Resources Preservation Act, which provides the same level of protection for fossils that archaeological resources had been granted 30 years earlier. I think it’s going to be a strong deterrent and has already shifted more commercial fossil collecting to private lands.

VS: I would have to say Yellowstone. When I first visited that park on that same cross-country trip at 13, I remember going in with a lot of excitement and expectation and departing with a tear in my eye because I didn’t want to leave. It’s a very special place, and the fact that I was hired to work there 20 years later was the thrill of a lifetime. I never imagined that could happen, and that experience profoundly influenced the way that I think and what I share with and teach my children. I’m very proud that during my time there I published the park’s first paleontological inventory. Being part of Yellowstone’s history is very fulfilling for me, and I’m honored to have contributed in that way.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.