by Allison Mills Friday, January 30, 2015

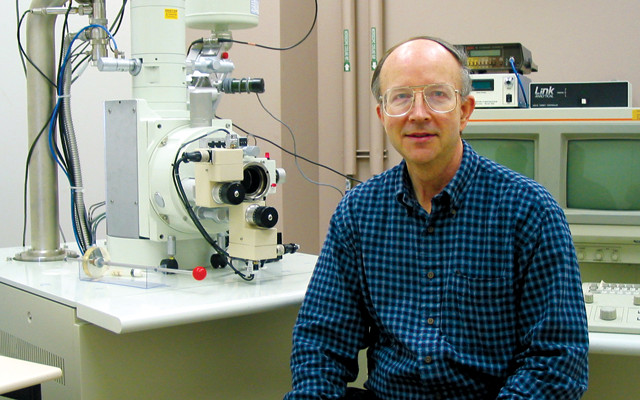

George Robinson has dedicated his life to finding, curating and sharing exceptional mineral specimens. Credit: John Jaszczak.

Many geologists understand the joyous feeling of coming across a beautiful rock in the field; George W. Robinson, who began collecting minerals at age 9, has had a lifetime full of such moments. After delving deeper into his early avocation as a teenager, he received his doctorate in mineralogy from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, in 1979. He has worked as a high school earth science teacher, field collector, mineral dealer, museum curator and professor — all occupations that shared a common focus: a love of minerals.

Robinson has traveled the world in search of mineral specimens, both common and exotic, and he recalls the provenance of each like a well-loved book. After a stint of mineral dealing with his wife Susan, a mineral artist, Robinson helped build up mineral collections at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, Ontario, and the A.E. Seaman Mineral Museum at Michigan Tech in Houghton, Mich. The rare lead-chromate mineral, georgerobinsonite, was named after him.

He is the author of several books on mineralogy, and in 2012 he received the Carnegie Mineralogical Award for his contributions to the field. Now in his 70s, Robinson still goes searching for specimens near his home in New York.

Contributing writer Allison Mills spoke with Robinson about his adventures as a collector, the nuances of displaying fine mineral samples, and what it means to be a connoisseur of minerals.

Robinson helped uncover some of the world's finest rare phosphate minerals along Rapid Creek in a remote area of the Yukon. Credit: George Robinson.

AM: What does it mean to be a mineral connoisseur?

GR: There are probably as many answers to this question as there are mineral collectors. To me, a connoisseur of mineral specimens is a person who understands and appreciates the significance of a given mineral specimen based on a broad spectrum of criteria. [This appreciation] generally comes with years of experience studying and handling such specimens. Locality, rarity and historic provenance rank — or often outrank — crystal perfection and the superficial aesthetics that win the favor of beginning collectors.

AM: Why did you switch from dealing to curating?

GR: While the mineral business was good, it did not pay benefits and was somewhat of a “feast or famine” venture. In 1982, a well-known curator at the Canadian Museum of Nature retired, so I applied for the position and was fortunate to get it. Because of federal conflict-of-interest rules, I could not personally collect minerals and be a curator too. So, my wife and I sold our private collection, and I began collecting “for them” rather than “for us.” In retrospect, it was the best decision I could have made. Being able to work every day with one of the world’s greatest collections, with minerals I could never have hoped to own, or being sent to collect minerals from exotic localities in the Northwest and Yukon Territories, Greenland and numerous others — and getting paid to do it — was surely an enviable job for any mineral collector!

In the late 1960s, the Mid-Continent Mine allowed visits by field collectors, including Robinson, who found this specimen in the calcite pocket shown. Credit: both: George Robinson.

AM: You have seen a lot of minerals. Do you have a favorite?

GR: If “favorite mineral” is interpreted as favorite species, then the answer would probably be tremolite. If, however, it is interpreted as favorite mineral specimen, then it would be a tie between the millerite on hematite from Antwerp, N.Y., originally from the Frederick Canfield collection and now in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, and the epitactic hornblende on diopside crystals from East Russell, N.Y., originally in the Clarence Bement collection and now at the American Museum of Natural History.

AM: What was one of your most exciting adventures while field collecting?

GR: While working for the Canadian Museum of Nature, I was fortunate to be able to visit many of the world’s great mineral localities. Among them was Rapid Creek in the far northern Yukon Territory, which is famous for its high-quality, rare phosphate minerals, including 10 species new to science. The four weeks I spent there made for an exciting adventure from start to finish. Imagine being dropped off by helicopter about 150 kilometers from the nearest outpost, where you would be camping out with grizzly bears and sharing your tent with hordes of hungry mosquitoes, necessitating dressing in bug suits and carrying a firearm at all times.

On one day’s venture from camp, we were offered a helicopter ride to a spot about 15 kilometers south of the main collecting area where the pilot claimed to have heard of prospectors finding more of the “blue crystals” like the lazulite we had been collecting at the principal occurrence. My assistant, Jerry, and I elected to go investigate it for a couple of hours while the helicopter made some other deliveries. About 20 minutes before our ride back to camp was due to arrive, we found a seam of what were the finest collinsite crystals known in existence. Just as we began to excavate it, here comes a full-grown grizzly bear walking down the streambed in which we were working. At the same time, we could hear the helicopter in the distance coming to pick us up. So, do you run to the rendezvous point to not miss your ride, scurry to the top of the streambed and hope the bear doesn’t see you, or stay and collect the world’s finest collinsite specimen? An easy choice for two die-hard collectors: I stood guard with the sights of the .44 Magnum I was carrying trained on the bear, just in case, while Jerry frantically scooped out the contents of the collinsite pocket into his knapsack. As luck would have it, the bear didn’t see us and it took a small fork in the stream about 30 meters from where we were working. While all the time keeping a close watch over my shoulder, we ran down the creek bed and back to our pick-up point just as the helicopter landed. The first words out of the pilot’s mouth were, “Hey, did you know there was a bear in the creek just below you?”

AM: What is the importance of making mineral collections accessible to the public?

GR: This is a question that can be answered by a simple exercise I used to pose to my high school earth science classes when we studied rocks and minerals. I would challenge them to look around the classroom at all its contents and find something that did not somehow depend on minerals or mining. They were never able to find such an object. Minerals have been the enablers of civilization from the Stone Age to the Space Age. Would we have cars, airplanes, computers or the space shuttle without them? It is essential to modern technology and society in general that people are aware of this. Making collections accessible for research, or using minerals as an integral part of educational, interactive museum exhibits that explain their importance, helps educate people in an informal way that simultaneously draws their attention to minerals and instills an appreciation for the natural world.

Millerite is a nickel-sulfide mineral that often grows in radiating sprays of needle-like crystals; this sample has needles as long as 9 centimeters. Credit: Chip Clark, Smithsonian Institution.

AM: How has mineral collecting and dealing changed over the course of your career?

GR: Opportunities for self-collecting good mineral specimens are fewer today than when I began collecting minerals decades ago, which perhaps explains why most members in rock and mineral clubs today are senior citizens.

The mineral-collecting community is currently changing from one composed of amateur mineralogists who collect minerals for both their scientific and aesthetic qualities, to one composed predominantly of collectors who view minerals as “natural art.” The latter are perhaps still fewer in number, but their combined wealth is enormous. That is dictating the value of mineral specimens in the global marketplace, driving prices to previously unheard of numbers. It has reached a point where many dealers are pricing their specimens as “price on request” rather than reveal their asking price. What used to sell for $10 to $20 at a mineral show now costs several hundred dollars or more, while really high-quality specimens of interest to museums and most serious collectors are priced in the five-, six- and even seven-figure range. How can a youngster with a budding interest in minerals compete at a mineral show with his/her paltry $10 allowance? It may cost that much just to get through the gate at one of the larger shows!

Fortunately, it is still possible to find lower-priced specimens at many of the smaller, hometown club-sponsored shows around the country, but with their aging memberships and lack of younger members willing to take over and keep the club alive, it may be only a matter of time before these opportunities are gone too.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.