by Zahra Hirji Wednesday, May 23, 2018

Jessica Whiteside (middle) is an assistant geology professor at Brown University. Credit: Courtesy of Jessica Whiteside

From Morocco to Connecticut, Jessica Whiteside has explored almost every Mesozoic rock outcrop there is. And she’s only three years out of graduate school. With a bachelor’s degree from Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Mass., and two master’s degrees and a doctorate from Columbia University in New York, N.Y., under her belt, Whitehouse is now in Providence, R.I., working as an assistant professor of geological sciences at Brown University.

Whitehouse is a paleobiologist, paleoclimatologist, geochemist and scientific illustrator all in one. She currently researches abrupt climate change events in the context of evolutionary trends and cyclical processes like Earth’s orbital variability. These events include the hothouse event in the Early Eocene, when hot global temperatures prevented glacier formation, and the icehouse event in the Devonian, when cool global temperatures allowed for glacier formation. Most recently, she has studied the Triassic-Jurassic mass extinction in conjunction with Earth’s largest volcanic province — the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province, which she argues did not play a role in that extinction event. The Triassic-Jurassic extinction event is one of Earth’s “Big Five” extinctions, resulting in huge extinctions of both land and ocean organisms.

Whiteside is known around the Brown community for her love of Diet Coke and her unique pets — a tarantula and a snake — that she brings for show-and-tell in her Fossil Records class. She recently spoke with EARTH contributor Zahra Hirji about her life, her research and the various adventures she has had along the way.

ZH: Growing up, your interests ranged from storytelling to chemistry, and yet you ended up in paleontology. How did that happen?

JW: I originally thought I was going to be the next Joseph Campbell and have a better, more modern version of “The Power of Myth.” I was really interested in comparing world mythologies … and how everyday languages and so much of society have been constructed upon or have their roots in these mythologies.

Growing up, I traveled extensively [with my family] throughout the American Southwest, which is where many of the most profound geological structures occur, including Zion, Bryce Canyon, the Grand Canyon and the Colorado National Monument. My dad explained how these formations had formed, and I saw that this was very similar to storytelling but had some tangible existence rooted in something that was physical. It was a really powerful, beautiful thing to me.

Chemistry was the same because I felt like that was the language that held everything together — just like the myths. Everything was rooted back to the story of the transfer of electrons. I was really just looking for a way to combine what I thought were hobbies, and it’s great to find out that you can get paid to do that.

Whiteside began drawing scientific illustrations in graduate school and continues to draw today to illustrate her own findings. Credit: Illustrations by Jessica Whiteside

ZH: You started conducting serious research in high school. How did you get that opportunity and what did the research involve?

JW: I was 15 when my twin sister and I started [attending] a boarding school that was in part created by Bill Clinton called the Arkansas School for Mathematics, Science and the Arts. It was a great experience because it was a transition from a very small town in Arkansas where the only option was essentially to work at the Waffle House … which we did.

We were really allowed to pave our own way in research. If we could figure out a research project, the school would transport us to the facilities we needed to conduct the research. The first year, I worked on an eco-physiology/plant project that combined chemistry and looking at low-level frequencies and microwave radiation [with the] eco-physiology of plants. The second year I worked in part at the University of Arkansas in Little Rock and the University of Arkansas Medical Sciences working on titanium peroxide as a photocatalyst to break down hydrocarbons in water.

Credit: Courtesy of Jessica Whiteside

ZH: What was your dissertation about?

JW: My thesis at Columbia was looking at catastrophic, climatic and biotic modulations of ecosystem evolution. I purposely wrote “ecosystem evolution” to distinguish it from “ecosystem development,” because I wasn’t just looking at external forcings of ecosystems like environmental factors or extraterrestrial impacts or volcanism or feedbacks related to Earth’s spin axis over time, but also the evolution of organisms and how that changes the biogeochemical cycle. I was primarily focused on the Mesozoic (250 million to 65 million years ago) because … [it] has three major mass extinctions: one beginning it, one ending it, and one basically in the middle. It also has the rise of dinosaurs.

ZH: To make extra money in graduate school, you drew science illustrations. How did you get involved with that?

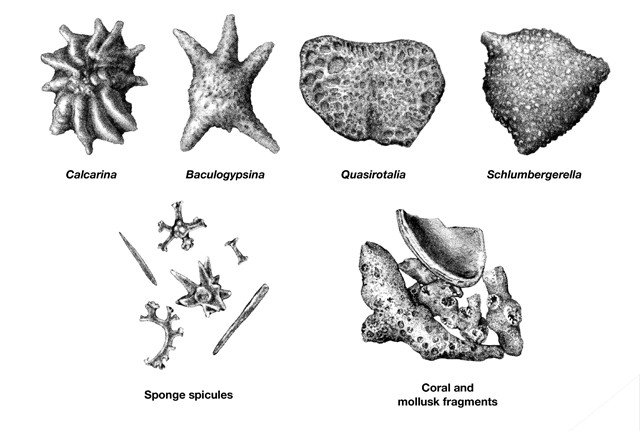

JW: I always doodled here and there. And I had drawn a lot of pictures of different protists (including Rubberneckia, which is the one where the interior region looks like it goes around in a circle. I love that creature.) A professor had seen my lab notebook and was somehow involved in publishing scientific literature on foraminifera, using them for [a] K-12 [project] to get students interested in science and asked me to illustrate. Then a few people saw those and asked me to draw some pictures.

ZH: Scientific illustration seems like a useful skill. Do you ever draw for your own research?

JW: Yes, when describing new species. Also it’s a great way to really observe the bones … another way of articulating what you see. The fossil record is imperfect in how it is preserved … it’s like a puzzle. Drawing it helps you to really say what you are actually describing.

ZH: Your research has taken you around the planet to 34 countries so far. Do you have a favorite?

JW: It’s hard for me to think of a favorite because they are all so different: I have seen most of the Mesozoic-aged rocks [that are exposed] on the planet. Morocco was really interesting — being in the Atlas Mountains — because I was working on the relationship between the Triassic-Jurassic boundary and the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province, Earth’s largest volcanic province. It actually isn’t just Earth’s largest, but it’s the solar system’s largest, something like 700 million square kilometers, which is larger than the United States and a third the size of the moon. And [the region is also] associated with the rise of dinosaurs. Just seeing that was a pretty powerful experience.

Whiteside has worked on fossils in the Devonian-aged Old Red Sandstone in Scotland. Credit: Dave Souza, © Creative Commons ShareAlike 3.0

ZH: Your current research focuses on rocks from the Devonian and Eocene, rather than the Mesozoic. Can you tell me about your excursion last summer to the fossil-filled Devonian-aged “Old Red Sandstone” cliffs in Scotland?

JW: It involves scrambling up the cliff if you are agile, and if you are a little more hesitant, it involves getting up on ladders and having someone steady them. These rocks are tide-dependent, but in some places they form ledges, [and] some actually form steps. Some of them you can only really see from aerial photographs or taking a boat. But we needed samples. It’s fascinating [when] you are discovering something and the harder it is to get to it, somehow the more deserving you feel.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.