by Allison Mills Tuesday, July 7, 2015

Fred Quivik is an industrial archaeologist at Michigan Tech. Credit: Michigan Tech.

Fred Quivik is no ordinary historian. Though he likes dusty books and archives to be sure, Quivik looks at history through objects, specifically the equipment, buildings and landscapes of industrial sites. He’s an industrial archaeologist, digging into the past of former mine sites, factories and other environmentally degraded places to see how they are connected to people and companies today. Quivik has done this sleuthing as a historic preservation consultant and as an expert witness in lawsuits dealing with Superfund sites. He has looked at sites across the U.S., focusing especially on the West, and now teaches at Michigan Tech University in Houghton, Mich.

Quivik spoke to EARTH contributor Allison Mills about their shared fascination with old copper mines, as well as about Quivik’s work in historic preservation and his experiences in the courtroom.

AM: What is industrial archaeology and how is it useful?

FQ: Most people think of archaeology as digging in the dirt, but the most important work archaeologists do is to analyze the objects they find to understand the people who made them. Traditionally, archaeology was used to understand people who did not leave a written record about themselves. But now, people are also using archaeology to supplement the historical period — and industrial archaeology uses artifacts to supplement the written record about industrial society.

__AM: What are some of the challenges in preserving industrial sites? __

FQ: One challenge is developing the resources to preserve large buildings that are no longer generating revenue. Because they’re so big, they take a lot of maintenance, and [the funds to do] that have to come out of the revenue stream they generate. If the buildings are no longer serving their [original] purpose, it’s difficult to pay to maintain them.

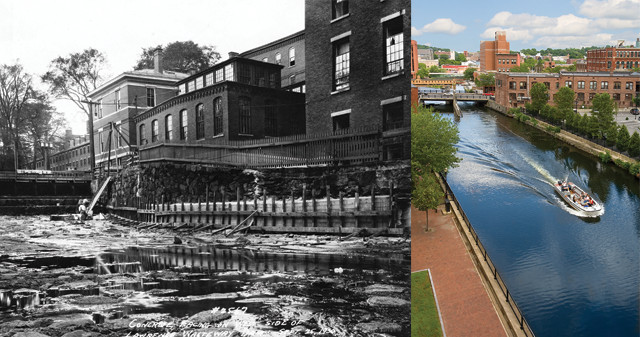

That’s why the concept of adaptive reuse is so important in historical preservation. We have to find new uses for industrial buildings … so that the industrial, historic character is maintained to the extent possible. The work done at Lowell, Massachusetts [where old textile mills have been converted into a National Historical Park] is a great model for how to deal with such a large-scale site.

ld textile mills in what is now the Lowell Historical National Park in Massachusetts helped jumpstart the Industrial Revolution in the United States, but also leaked contaminants into the environment. The park is an example of successful historic preservation and ecological restoration. Credit: both: National Park Service Archives.

AM: What has your experience taught you about the repercussions of industrialization?

FQ: Industrialization is, in part, about scale, and a corollary to that is that industrial systems produce waste on unprecedented scales. That’s why we have the Superfund program in the United States to clean up these severely contaminated sites, where the scale of contamination boggles the mind.

So, that’s one set of social objectives in the United States, to clean up the environment. Another set of social objectives is to preserve and interpret our heritage so that future generations can understand important lessons from the past. When you bring those two together in an industrial site, conflict can arise.

AM: On which of those two sides do you find yourself?

FQ: I was an environmentalist before I became a historic preservationist. I was in architecture school and was frustrated because all we were learning was how to design new buildings — and I saw lots of old buildings that were sitting around not being effectively used. Typically, they would be demolished and new buildings would be built. As an environmentalist, I recognized that as a waste of resources. So, I wanted to learn tools for reusing existing buildings, for environmental purposes initially. Then along the way, the history bug bit me. I became interested in and passionate about [preserving old buildings] for historical reasons too.

But I am in full sympathy and a strong advocate of the need to clean up hazardous materials at old industrial sites. I think that it’s possible — and I’ve seen it work — to satisfactorily combine those two sets of social values, both hazardous material remediation along with the preservation and interpretation of cultural resources. That is, if the people involved are willing to take on the design challenge.

__AM: How can remediation and preservation work together? __

FQ: I will say the difficulty lies on the remediation side, with people who are pretty narrow-minded in their approach to remediating hazardous materials. They have an antagonistic attitude toward industry as the cause of the problem — which certainly is true — and so they would just as soon obliterate all traces of the industrial past, cover a site with grass and call it cleaned up. But then future generations will not be able to learn from the physical experience of that site. It makes it look like whatever industry had been there must have been benign because it’s just a grassy area.

I would like to see remediation efforts designed to make sure hazards are addressed, while also preserving, where possible, industrial remains. Then, we can not only interpret that industrial past but also, later, the significant history of remediation, a period that we are passing through now.

Quivik served as a historical advisor, focusing on the technological developments of copper mining, for the Clark Fork River Superfund Site, which is now undergoing remediation. Credit: Allison Mills.

AM: How have you been involved in court cases as an expert environmental consultant?

FQ: Historians develop and write expert opinions, just like other technical experts and scientists develop expert opinions in a litigation setting. Most, but not all, of the cases I’ve worked on have been Superfund cases. There is often a need for a historian to research some aspect of the site’s past and use the empirical methods of history to tell a narrative that will be useful to the judge.

AM: What is the most interesting case you have worked on?

FQ: I worked on a case with the U.S. Department of Justice on the Clark Fork River Superfund site in Montana, which contains Butte, Anaconda and the Clark Fork River all the way down to Missoula [nearly 200 kilometers away] — the largest Superfund site in the United States measured in geographical area. For that case, I had the opportunity to research copper and zinc concentrators, silver and manganese mills, and copper smelters. The focus was on the changing technologies that [companies] used for mineral processing, how they discharged waste products and how they managed them, if they did — all of which, from the [federal government’s] perspective, demonstrated that ARCO, the large oil company that bought out the Anaconda Copper Company, was responsible for bearing the cost of that Superfund cleanup.

AM: What drew you to teaching at Michigan Tech?

FQ: I’ve done some teaching on the side for quite a few years and I’ve been associated with the Society for Industrial Archeology since 1980. They’re headquartered at Michigan Tech, so I’ve known many of the folks in the social sciences department for quite a few years. Just as my wife and I decided to leave Philadelphia, there was a job opening here, and it seemed like a nice opportunity to see what full-time teaching was like.

And one added attraction was that Houghton, Mich., is located in the midst of another important historic mining district, the Keweenaw Peninsula. So the opportunity to draw some comparisons to Butte seemed promising.

Plus, for decades now and for some strange reason, I have loved to shovel snow. I think living on the Keweenaw (which receives more than 5 meters of snow on average each winter), I’m being cured of that finally [laughs]. And in the summer, there are great places to go hiking. Long before we moved to Houghton, we fell in love with Lake Superior; it’s one of the most spectacular bodies of water I have ever seen and I love spending vacation time on Minnesota’s North Shore.

Left: A waste-filled canal in Lowell, Mass., where water-powered textile mills sprang up along the Merrimack River at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Today (above), tourists explore the restored mills and canals at the Lowell National Historical Park. Credit: both: National Park Service.

AM: How do you connect the past and present?

FQ: I enjoy burying myself in archives, old technical journals and getting some sense of the long development of a place’s history. Getting familiar with the physical layout and landscape is important, and after having spent time physically in that place, I’m able to make connections in my own mind between the physical landscape and what I’m reading in the historical record. And that begins to take shape as a historical narrative.

The challenge then is to figure out how to present that historical narrative in a way that is meaningful to people, given present-day questions and concerns.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.