by Terri Cook Sunday, January 4, 2015

As a child growing up in Gassaway, W.Va., Lonnie Thompson was poor. When his father died while Thompson was a senior in high school, he realized he’d need to earn a reliable paycheck as quickly as possible. As an undergraduate at Marshall University in Huntington, W.Va., he knew he wanted to study science; he started off as a physics major before settling on geology. Later, when he arrived at Ohio State University (OSU) as a graduate student in 1971, Thompson’s intent was to study coal geology, a practical choice that he believed would quickly secure him a job.

During his first term, however, Thompson received a notice in his mailbox advertising a research position to examine ice cores at OSU’s Institute of Polar Studies (now called the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center). Thompson knew that glaciers cover just 10 percent of the planet, and that they’re mostly located in places where people don’t live, so he doubted he could ever make a living looking at ice. But he also knew that he could earn his degree more quickly if he held a research position, so he applied for the job.

That decision ultimately led to an illustrious career studying glacial ice. After several years deciphering the climate records preserved in the earliest cores retrieved from Greenland and Antarctica, he pioneered the study of glaciers in Earth’s tropical and subtropical regions.

Thompson has received dozens of awards for his work, including the National Medal of Science and the Seligman Crystal, the International Glaciological Society’s highest honor. In 2005, he was elected as a member of the National Academy of Sciences and a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and in 2009, he was selected as a Foreign Member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Thompson holds a joint appointment as an OSU distinguished university professor in the school of earth sciences and a senior research scientist in the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center, which his wife, Ellen Mosley-Thompson, a distinguished university professor in OSU’s department of geography, directs. Thompson recently spoke with EARTH contributor Terri Cook about the circumstances that launched his career, how a successful heart transplant in 2012 has influenced him, and why as a child he would bet his lunch money on the weather.

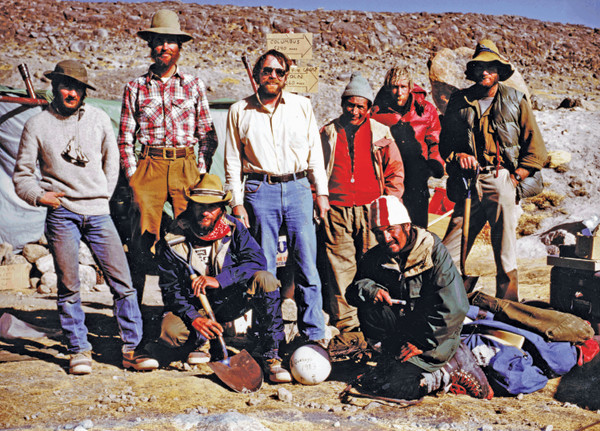

Thompson led the team that first successfully cored a tropical glacier to bedrock at Quelccaya in Peru in 1983. It took three months to recover two cores. Credit: Lonnie Thompson.

TC: How did you become interested in science?

LT: In sixth grade, I became interested in the weather. I set up a weather station in the barn on our farm, and I became pretty good at predicting it. We were very poor, so at school I’d bet my lunch money on the forecast. Unfortunately, when you grow up in a poor community, there’s a lot of negative feedback that discourages you from trying new things and keeps you from dreaming. It takes a lot of courage to overcome the negativity, and this was why it was so important to have motivated teachers and fellow students to inspire me and a mom who always stressed the importance of education.

TC: Why did you decide to take a risk and deviate from your plan of studying coal geology?

LT: I think circumstances in my early life played an important role. Two years after my dad passed away, my sister died in an automobile accident when she was only 19. Those events really brought home the fact that there are no guarantees in life, and that if you want to make a difference, you need to get on with it. To do that, you have to take risks. I’ve always felt that in life it’s not really what happens to you, but how you choose to deal with adversity that’s most important.

TC: What events focused your research on tropical ice?

LT: While working on my dissertation, I began thinking about trying to connect the research that was coming out of Antarctica with what was coming out of Greenland. It was a fascinating time because all the pioneers in our field were alive, including John Mercer, who had compiled two atlases of Earth’s glaciers while working at the American Geographical Society. When Mercer came to OSU, he had boxes of aerial photos from around the world, and in those boxes, we found images of the Quelccaya ice cap in the Peruvian Andes. That set the stage. Once I visited the ice cap, I could see there was a climate record there. It then became a matter of how to extract that record.

To recover two cores, in 2010, Thompson's team camped at an elevation of almost 4,900 meters atop this glacier near Puncak Jaya in Papua, Indonesia, one of just a few glaciers between the Himalayas and the Andes. Credit: Lonnie Thompson.

TC: What role has luck played in your career?

LT: Drilling Quelccaya first was a lucky choice. We now know that it is the best site that we could have possibly chosen to look for a low-latitude record. We’re still extracting new records from it 40 years later. Had Kilimanjaro been the first, we would never have figured [the record] out, because the surface of Kilimanjaro is not modern; it’s ablated. There’s serendipity in all these things, including the people you meet along the way. In general, a lot of success is built on the efforts of other people.

TC: Your initial expedition to Quelccaya failed in the first hour when the helicopters couldn’t carry the gear up to 5,800 meters. How did you convince the National Science Foundation to keep funding you?

LT: That was my biggest failure; it shouldn’t have happened. I had met with the helicopter crew the year before, and they said it’d be no problem to fly the ice drill in. But by the time the next year rolled around, there was a different crew. People have to be committed and willing to take risks to make things work. When that failed, we climbed up to the ice cap, sampled 25 meters down the wall of a crevasse, and extracted a 25-year record of El Niño events that we published in Science. We then began to develop a solar-powered drill that would break down into units that we could put on horses to make the two-day journey from the end of the road to the ice cap. But of course we needed funding, so we wrote another proposal. Fortunately, the Office of Climate Dynamics had a new program manager, Hassan Virji, who, despite some poor reviews, was willing to take a chance and fund us. If you got those kinds of reviews today, you wouldn’t get funded, which is a problem. The idea that you have to know if something works before you even try it is really going to limit breakthroughs in science.

Thompson and his wife Ellen Mosley- Thompson, director of the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at Ohio State University, in the ice-core storage facility. Credit: Lonnie Thompson.

TC: Is there any advice that you would give to young researchers?

LT: I think you should listen to your elders because they’ve had experience, but at the end of the day, you’ve got to go with what you think is best and do your utmost to make sure you succeed. I’m a firm believer in the 10,000-hour rule: If you’re going to be an expert in anything, you have to put in eight and a half to nine years of learning. When you’re young, you can afford to make mistakes. That’s the time to take risks; if you do and it works out, then you can change the whole direction of thinking. That’s what science should be all about.

TC: Of all the awards you’ve received, which is the most meaningful to you?

LT: The first one, which was the Vega Medal from the Swedish Society [for Anthropology and Geography]. There was no money associated with it, but it was the people who had won the award previously — heroes like [Fridtjof] Nansen, [Robert] Scott, [Roald] Amundsen and [Richard] Byrd. These are the people I read about while growing up, and to think that I was awarded a medal that they had also received doesn’t seem possible.

TC: What emotions have you experienced while working with glacial ice cores?

LT: Every time we drill at a new site, there is excitement when you finally hit bedrock, when you’ve accomplished a mission in a really remote part of the world that a lot of people would have said was impossible. My repeated trips to Quelccaya [which is melting] are also emotional; I’ve often thought of it as visiting a terminally ill patient. You know what’s happening, and you know what the future will be. This ice is an extremely important part of our environment that I’ve had an opportunity to see and study [but] that future generations will not.

TC: When did it dawn on you that you were gathering not just a record of past climate, but also a record of human history?

LT: Quelccaya was the first place. The studies we wrote on the first core extracted with the solar-powered drill have been quoted in about 60 archaeological papers. To me the beauty of these ice studies is that we have an opportunity to work with scientists in other disciplines and learn from their perspectives. We bring to the table a calendar, and a temperature and precipitation history. In those early cultures in Peru, especially up on the Altiplano, both temperature and precipitation were critical to whether a civilization could exist there or not.

Thompson, winner of the 2005 National Medal of Science, was awarded the medal in a 2007 ceremony with President George W. Bush. Credit: Ryan K. Morris, National Science and Technology Medals Foundation.

TC: What did your experience of receiving a heart transplant teach you?

LT: For a time it wasn’t clear what the outcome would ultimately be. The situation was life threatening, but I learned a lot about myself and the people around me through it. For six months I survived on a turbine that was installed in my old heart. It was the bridge that allowed me to wait for a new heart that was a good match. I knew that I’d had 63 great years, and if the operation were successful, I’d have a few more. The worst thing I can think of is to live a life in which, when you’re my age, you look back and wish you’d done something else. Life is not about living to be 100, but about making a difference while you’re here.

TC: With this new heart, you’ve been given the gift of a second life. What do you hope to accomplish in it?

LT: I’ve thought a lot about that question. Certainly, there are a few additional [ice] records that I want to get, but I don’t think that is my real purpose. I think that there’s another opportunity, a more personal one, and I’m still sorting out just exactly what that is. I think, in all of us, there is a life force that connects us. I’ve noticed this in all the countries where I work. Once you get away from governments and deal with people, we’re all the same, and somehow in that connection there should be a way to get us to work together to change the future of this planet. I’m really concerned about the track we’re on; we haven’t done anything to change our future. It wasn’t my choice whether I wanted a heart transplant; it’s the way things were. I believe it’s the same with climate change issues — at the end of the day, we will deal with them because we’ll have to.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.