by Terri Cook Monday, June 8, 2015

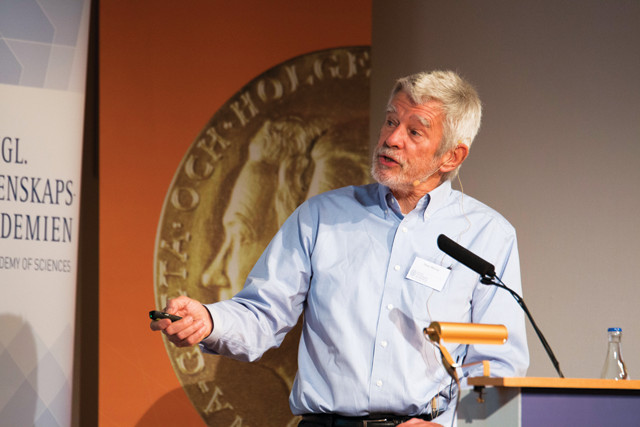

Peter Molnar is a professor in the Geological Sciences Department at the University of Colorado at Boulder and a fellow of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences. Credit: David Oonk/CIRES.

As a graduate student in geophysics at Columbia University in the late 1960s, Peter Molnar — who had studied physics as an undergraduate — decided to sit in on a geology course for a term. When the professor began discussing cratons one day, Molnar raised his hand and asked what a craton was. Molnar still remembers the strange look he received, as if the professor were wondering, “Who let this guy in?”

It’s fortunate that Molnar — and the professor — persevered. Molnar has gone on to an exceptional career in geophysics, underscored by his receipt last year of the Crafoord Prize in Geosciences, one of the world’s most prestigious scientific honors. Awarded to a geoscientist once every four years by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the 4-million-krona prize (nearly $600,000 at the time) honors achievements in fields not covered by the academy’s better known Nobel prizes.

Molnar, a professor in the Geological Sciences Department at the University of Colorado at Boulder and a fellow of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, was recognized by the academy for his “ground-breaking contribution to the understanding of global tectonics, in particular the deformation of continents and the structure and evolution of mountain ranges, as well as the impact of tectonic processes on ocean-atmosphere circulation and climate.”

Early in his career, Molnar, along with Bryan Isacks, now at Cornell University, pioneered the use of seismological techniques to investigate plate tectonics. In particular, they demonstrated that “slab pull” due to oceanic crust sinking into the mantle at subduction zones provides one of the main driving forces that move Earth’s plates.

Molnar is well known for his research on continent-continent collisions, especially in the Himalaya Mountains. And he has received recognition for his fundamental work defining and measuring the surprisingly complex concept of uplift. Molnar’s research also includes earthquake prediction and risks, dynamic topography, and the opening and closing of seaways between continents, which has added to our understanding of ocean circulation and its influence on climate on geologic timescales.

Molnar recently spoke with EARTH contributor Terri Cook about why he’s changed directions multiple times during his career, why it’s good to be contrarian, and why he’d become an anthropologist if he didn’t already have a job he loves.

TC: In your popular science book, “Plate Tectonics: A Very Short Introduction,” you discussed how plate tectonic processes were primarily recognized by young scientists while the “established giants” in geology were busy looking at the moon. Why do you think it was mostly young people who made these discoveries?

PM: When you get older, you become less flexible; you see all of what could be wrong. It’s much harder to accept something new when you have all this baggage. When you’re young, you’re more able to charge forward, whereas older people can get stuck. Many of them get bored. I try to stay young by changing direction so that I don’t get stuck. I switched from [studying] plate tectonics to continents, which forced me to learn geology. That’s when I began to learn about cratons. I had to grope my way through, but it was an obvious opening [into an area ripe for discovery]. Then I got into climate. Now I’m trying to learn a bit of biology.

Molnar receiving the 2014 Crafoord Prize from the King of Sweden at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm in May 2014. Credit: Markus Marcetic.

TC: Why has your career not included much teaching?

PM: I was a lousy teacher. I would go from being excited in September to being increasingly discouraged, following a sawtooth curve of enthusiasm that declined until May. Then I’d go off into the field and my state of mind would improve. Fieldwork is a necessary part of my life because whenever I see a place, my understanding of it changes. It’s never the way I imagined it, and that’s good.

__TC: I read that you received some C’s in college. Why was that? __

PM: I had eight C’s when I was in college, one in almost every class in which I had to write. The only semester that I didn’t get a C was when I took only math and physics courses. It took years for me to learn how to write well. Three things helped. One was that I worked and worked at it. I also dealt with many people whose native language wasn’t English, so I learned how to simplify my language. I learned to expunge difficult words like “get” — as in “get well,” “get sick,” or “get an idea.” It’s really idiomatic. My wife, Sara Neustadtl, who is a writer, has also helped me. But it’s still not easy. I don’t just sit down and write; I ponder every word. The couple of times that I’ve seen my work plagiarized, I’ve recognized it immediately because I had sweated over every word.

TC: How did your parents influence you?

PM: I was very strongly influenced by them. My mother had an aneurysm rupture in her head when I was 2, so she was paralyzed my entire life. Because she was handicapped, my father had to do everything. He was a tower of strength, a very big man, 6 feet 3 inches tall, imposing in all ways, and demanding. My relationship with him was tense, particularly when I was in college. Socially he was very open, but politically he was conservative — a Republican to the core. I was a socialist; I still am. So we didn’t get on.

But he instilled many values. In fact, what I have learned from my father, I’ve actually learned since he died, when I was 29. His death allowed me to become myself. Before, I was always trying to live up to his standards, and they were too high. But once he was gone, I could develop my own standards. Ironically, I think he died satisfied. The last time that I saw him coherent, I had just gotten a job offer from MIT. He had worried that I was going to be a total failure, and not without reason. But I think he died realizing that I was going to be OK. My mother was as important an influence as my father. She stuck by me whenever I got in trouble for misbehaving, and when I was struggling with my father. Despite paralysis of her entire left side, she was the foundation, the strength that kept us together. I have never met anyone who could undergo pain as she could, and if she could do something, I should have been able to do it too.

Molnar presenting the Crafoord Prize Symposium on mountain belt dynamics at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm. Credit: Victoria Henriksson.

TC: When did you discover how much mountains mean to you?

PM: In 1952, when I was almost 9, my father decided to show our family the West. So he took three weeks off, some of it unpaid, and we drove across the country from New Jersey. The first place we arrived that was interesting was Estes Park, Colo. I saw the Rockies, and I was blown away. I still get nostalgic when I hike in Rocky Mountain National Park. We went down to the Royal Gorge, drove up Pike’s Peak, and saw the Grand Canyon, the Tetons and Yosemite. That was one of the most important experiences in my life. Then, two years later, when my father attended a conference in Europe, my parents pulled me out of school for two months, and I saw the Alps, which were even more spectacular. I quickly learned that mountains were what really interested me.

TC: Did you ever consider a different career?

PM: If I could find another job, it would be as an anthropologist … although I have no ability for foreign languages, and I’d have to be a better writer. Anthropology was a dream because I was always curious about the cultures where I was living. When I worked in Africa, I picked up hitchhikers all the time as I drove around changing seismograms. The Masai would get into the back of the jeep, and their spears would reach past my ears. They weren’t going anywhere in particular; they just liked to go for a ride. I was always curious to know how these people were living. Doing fieldwork, I was grateful that I could stay in one place long enough to see it from different perspectives, unlike a tourist.

TC: What have scientists learned so far from the April 25 earthquake in Nepal?

PM: It was a surprise only in the sense that it was a little smaller than I had expected. Of course, I had no idea when it would occur, just that it would. There have been earthquakes [in the Himalayas] larger than this one in the past; there are radiocarbon dates that suggest there was a big earthquake around the 12th century, and strong indications from the devastation of monasteries in Tibet that there was a very large earthquake in 1505. If you take the kind of numbers we’re talking about — 500 years times roughly 20 millimeters of slip a year — that’s 10 meters of potential slip. There were only 3 meters of slip in [the April 25] one, apparently … So, the potential for a much bigger earthquake is hard to deny.

__TC: You are fond of saying that when something seems complicated, it’s because we don’t understand it. What’s behind that notion? __

PM: I’m of the opinion that simple is beautiful; my father taught me that. I also think that there are two parts to understanding. One is being able to reduce ideas to general principles, and for most of the physical sciences, that’s an algebraic equation. This applies to many things, including plate tectonics. It only takes three numbers to describe plate motion: a latitude, a longitude and an angular velocity. You can reduce the entire large-scale movement of Earth to a few numbers. You don’t have to know the dynamics of plate motion; you don’t have to know the forces. You can still make all the predictions that you need for the interaction of the plates themselves. That’s beautifully simple. The second half of understanding is something that’s emotional — asking yourself if it sits right in your stomach, if it feels right. For true understanding, you need both parts — the clearly explainable part, and the emotional part.

Molnar and his wife, Sara Neustadtl, rafting down the Yangbi River in western Yunnan, China, during a field research trip to investigate the climatic effects of the tectonic uplift of the Tibetan Plateau. Credit: Ben Foster.

TC: How do you decide which topics to focus on in your research?

PM: I’m motivated by curiosity. My wife says that I like to find something that’s widely accepted but that doesn’t quite make sense, and then find out why it’s wrong. In some ways she’s right. I like to go after ideas that don’t make sense. But I also like to think that I try to do better than show how everybody’s wrong — I actually try to figure out what’s right as well. One of the ideas I’ve been pursuing is the timing of the emergence of Panama, and its relation to the ice ages. There are absurdly different explanations: Some textbooks say that its emergence 2 million or 3 million years ago triggered the ice ages. Others say it did not. But Panama has been there for 15 million or 20 million years! It’s fun when the textbooks are wrong; you know you’re onto something good.

TC: Do you see yourself as a contrarian?

PM: Yes. If you want to make progress, you have to work at the edge, where there is controversy and disagreement; you have to be contrary. It’s most fun when nearly everyone is wrong, because that’s when you can make a breakthrough.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.