by Allison Mills Monday, November 3, 2014

Nicole Barlow runs Purple Rock, Inc., a company she created to mine for nuggets of geologic knowledge stashed in old documents that fill up store rooms, boxes and filing cabinets. Credit: Nicole Barlow.

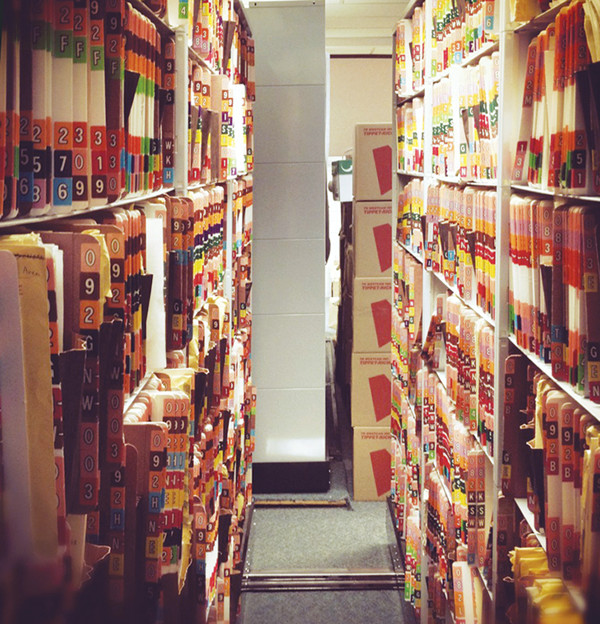

Miners are the classic geo-entrepreneurs. Nicole Barlow is a new kind of geo-entrepreneur: She also mines — but instead of rocks, she digs into dark data. That’s all the information stored away in file cabinets, boxes and geological survey store rooms. And instead of finding gold or silver, she uncovers nuggets of information and digitizes old documents.

Barlow runs Purple Rock, Inc., a company she started in Victoria, British Columbia, to help geoscientists with technical editing and data management. After starting off in editing services, helping journals and researchers better communicate their science, she realized that companies and geological surveys possessed a vast, underutilized resource: their paper files. As an intern at the British Columbia Geological Survey (BCGS), then as a project leader and now as CEO of her own company, Barlow has meticulously gone through every single paper in the BCGS archives, scanning them and indexing the information. She calls the work “unlocking the paper vault” and says the forgotten documents can be a goldmine for companies and government agencies.

Barlow spoke with EARTH’s Allison Mills about what it’s like to lead her company, find old documents and spearhead her team’s success.

AM: What first got you interested in geology?

NB: I’ve always loved rocks. My parents tell stories about when I was 2 years old and I would keep picking up rocks off the path, giving them to my dad to hold, and his pockets would get heavier and heavier. He would start dropping some behind him and I would see that he had dropped one — so I would pick it up and give it back to him.

I like that rocks are solid to a certain extent, at least within human time frames, so it’s something permanent that you can study and you can put on your desk and look at and analyze. … You can’t go anywhere on Earth without geology being there, and there’s always something different to look at.

Stacks of old field notes hidden away in storage can contain valuable bits of information that can be useful to geologists. Credit: Nicole Barlow.

AM: How did your business get started?

NB: I’ve always loved organizing and libraries — and I’m an avid reader. From the editing side, I’ve always loved English classes and the English language, so tying all my interests together just made sense.

But a geology editor I worked with told me that you couldn’t really join a geological editing firm: You had to start your own company. So I expected to be self-employed, working and editing from home with my own freelance clients — and then the work just snowballed into something bigger. When I saw the number of documents that needed to be processed — that this was a rampant problem across the entire industry and, for most companies and jurisdictions, everything was still on paper — I realized I had to start developing a team. I got started by bringing together document experts, organizers, geologists and software engineers.

Most geoscience organizations have a warehouse of dusty old boxes in their back room that no one has really gone through, and the institutional memory of what’s in those boxes [like mine exploration data, detailed stratigraphic notes and maps] has disappeared. We go through every single document, assess the geologic relevance, get it scanned and provide a metadata index. All of that becomes a PDF, which is fully searchable and uses a Web interface. It’s basically Google searching your filing cabinet.

AM: What is it like sorting through so many documents?

NB: It’s kind of a treasure hunt every day. It’s not necessarily the most scintillating activity to look through every single piece of paper that someone might have in their archives, but you’re looking for nuggets of knowledge and information that might have fallen through the cracks.

When you think about it in a big picture context, this archive could provide the next big find — perhaps information about a mine that could last for decades and employ hundreds of people and change the economy of an entire region. That’s when the day-to-day work becomes very exciting.

And we work on both ends of a temporal spectrum: We deal with old archives as well as new documents that haven’t been published yet. It’s great to see how geological ideas have changed and how they’ve stayed the same.

Barlow and her team have looked at documents as old as 160 years; many, like these rolled maps, were made throughout the past century. Credit: Nicole Barlow.

AM: What is the oldest document you have digitized?

NB: We’ve worked with a lot of reproductions from around 1900, but the oldest was an onionskin paper with typewriter marks on it from about 1850. There are also a lot of hand-drawn maps and they’re absolutely beautiful — the penmanship that people had back then is just amazing!

AM: Women are underrepresented in geoscience and business. What is it like being in both worlds?

NB: I would say that it’s an interesting position to be in, being a young woman in both business and geoscience. Geo-data management is a unique industry in that it’s a niche that isn’t well served, so it’s not only that as a woman I’m a minority in both fields, but my company is a minority in geoscience circles. I don’t know if either of these unique qualities is necessarily positive or negative, but they definitely make us stand out from other companies at a trade show.

Being young and being the CEO of my own company, it’s sometimes a challenge to get people to take me seriously. … I find email [communication] is just easier because people aren’t seeing me as a young woman, they’re seeing me as a CEO sending an email. But given where we are as a company, our experiences, and the more than 100,000 documents that we’ve gone through, people look at that and see competence, they see that we can deliver. … At trade shows, people see that expertise and, with the company being eight years old, people recognize the name Purple Rock. And people see the work we’ve done — and that speaks for itself.

AM: What do you do when you’re not working?

NB: Sometimes there is time for life outside work — often not [laughs]. My husband and I love to travel. Every year, we head to Hawaii or Europe or somewhere else to explore. When we’re at home, we’re working; it’s kind of like being on call 24/7 for whatever a client needs or the staff needs. But when we’re on holidays, we’re on holidays. So that’s our break, our condensed weekends all together. Also, I have a wonderful puppy that loves to go for walks and loves to taste-test; one of my hobbies is being in the kitchen and baking.

Barlow started her work with the British Columbia Geological Survey and has gone through the paper archives there sheet by sheet. With her team, they have made more than 70,000 documents publicly available online. Credit: Nicole Barlow.

AM: You were hands-on with your company’s projects early on; what is it like now stepping back and leading a team?

NB: As the company has grown, I’ve been finding that my favorite part of the job is building the team and working with the clients. But it’s difficult to learn to delegate, to let things go. Of course, unless you do that, you can’t grow as a company. … When it was just me and three other people or so, I was definitely working with every single document and making sure that everything was exactly how I wanted it to be. Learning to delegate is a big part of being a manager and being a CEO, and most of my days are taken up with emails and phone calls, looking for new contracts for my team.

AM: What has been your biggest success so far with the company?

NB: Everyday seems like a new success, because we find new documents all the time that are interesting. But the true success is just the sheer volume of the information that we’ve been able to make public. With the British Columbia government, we’ve been working with them for almost eight years and we’ve put more than 50,000 documents online; with the Yukon government, we’ve put another 20,000 documents online. And with both geological surveys, we’ve culled about half the existing documents, so we’ve actually gone through twice as much as what is posted online.

Getting information out there has been the greatest success, especially because some documents are so fragile. We’ve had to use crazy different methods to peel apart pages that have been stuck together, for example. And much of that information is valuable and unique. Preserving that knowledge before the ink disintegrates, before the film degrades or before the paper crumbles into dust, I think that is our biggest contribution. We are making [the documents] last longer and making them available to the next generation of geologists.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.