by Jay R. Thompson Thursday, December 18, 2014

Brian Tucker, founder and president of GeoHazards International (GHI). Credit: courtesy of the MacArthur Foundation.

Some of the world’s most densely populated cities are at highest risk for earthquake-related disasters. Geophysicist Brian Tucker has spent the last two-plus decades trying to help the developing world avoid such disasters, and in 1991, he founded the nonprofit GeoHazards International (GHI) to bring the developed world’s risk-mitigation techniques to high-risk communities in the developing world.

In the decades since, Tucker has been named a MacArthur Fellow, has received the George Brown Award for International Scientific Cooperation, and was selected as one of the 100 most influential alumni of the University of California at San Diego. He also received the Gorakha Dakshin Bahu Award, the highest honor awarded for service to the nation and people of Nepal, which was personally awarded to Tucker by King Birendra just months before he and the royal family were assassinated, reportedly by the king’s son, in 2001.

Tucker recently spoke with EARTH contributor Jay R. Thompson about geological hazards, meeting a king and about competitive rowing with neither a boat nor water.

JRT: Where are the most vulnerable communities in the world and what makes them vulnerable?

BT: The most vulnerable places are where poverty, rapid population growth and earthquakes intersect. That “wonderful” cocktail is found all over the world. Many of the most vulnerable regions are in the Alpine-Himalayan Mountain Belt: Start from the northern border of Turkey and go east through Iran. Tehran is one of the most vulnerable communities — the city is built on a huge fault. Then continue eastward through Afghanistan, Pakistan, the northern boundary of India, then Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Burma, and then wrap down through Indonesia. Rapidly growing population and poverty is an awful combination. It’s hard enough to build good buildings with a strong economy and government.

JRT: What’s the worst-case scenario you’re attempting to prevent?

BT: I think to a large extent we saw it in Haiti. But there, things weren’t even as bad as they could have been, or as bad as they’d be in other places. Because Haiti is on an island, the Navy could park a hospital ship offshore, and there were some airports where supplies could be brought in. But places like Bhutan and Kathmandu [in Nepal] are really isolated. If a major earthquake struck there, the economic and human losses would be terrible. There are a lot of terrible things happening in the world, but I think it is in everyone’s interests to help these poor countries continue to develop.

JRT: With a B.S. in physics, an M.A. in public policy and a Ph.D. in earth sciences, it looks like you had a plan from the start.

BT: That’s really funny because I didn’t earn the degrees in that order. It wasn’t a plan, but I guess there is a thread … I wanted to do what was socially relevant. Earth science seemed like a good social application, so I went from an undergraduate in physics [1967, Pomona College] to graduate school in geophysics at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California at San Diego.

After grad school, I got a life-changing opportunity to live in Tajikistan. It was a U.S.-Soviet program on environmental protection, and part of the program was earthquake prediction. The Soviets sent some of their seismologists to the U.S., and U.S. seismologists went to the Soviet Union.

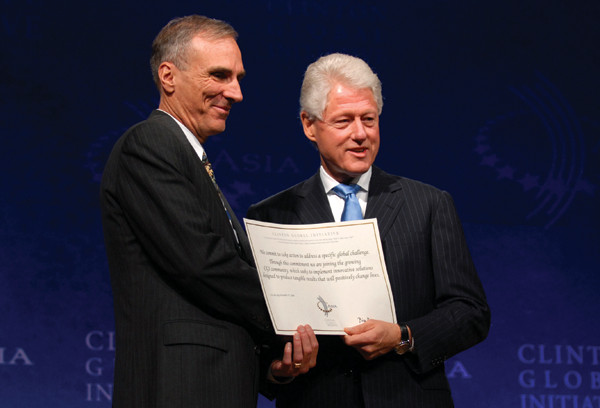

Tucker accepts an award on behalf of GHI from former President Bill Clinton at the 2008 Clinton Global Initiative meeting in Hong Kong. GHI was recognized for its proposal to use tele-engineering in South Asia to help improve earthquake safety. Credit: courtesy of the Clinton Global Initiative.

JRT: How was that life changing?

BT: In a number of ways. I always took different routes into Tajikistan — through Afghanistan, Turkey, Greece, for example. I saw that most people dying in earthquakes were not in wood-framed homes, but in adobe houses.

In addition, this experience made me realize that academic research was too far — for me — from application. This eventually led to me accepting an offer to head up the California Geological Survey’s geological hazards program, and that seemed to me like a good way to apply the science to public policy. After leading that program for about eight years, I realized that my academic training didn’t provide me with certain tools and knowledge needed for the job. So I took a leave of absence and went back to grad school at the Kennedy School of Government, at Harvard, for public policy. It was in that period that I reflected on the fact that California was in good hands concerning its earthquake risk, but many of the countries I had visited around the world weren’t. That’s when I decided to found this nonprofit.

JRT: What does GHI do?

BT: We start out by identifying a city with high earthquake or tsunami risk and finding a local person with whom we can work and who wants to work with us. These local champions come in all shapes and sizes: from government officials to NGO [nongovernmental organization] leaders to college professors or even school principals.

We write grant proposals to whomever we think might be interested, from the National Science Foundation to the World Bank. Then we design projects to work with the locals over two or three years, and we come in intermittently to push the program along. After a few years, the locals are off and running — if all goes according to plan — and we go to another spot.

In some places, however, we found that the problems were so big, and the need to constantly interact with the government or with local NGOs and with society was so great, that we established a more permanent office. That’s the case in India and now Bhutan as well. But that’s still not the norm.

JRT: What has been GHI’s greatest success as an organization?

BT: I would say our biggest success was working with the nonprofit National Society for Earthquake Technology in Nepal. It was a very small organization. Because of our rolodex, we were able to help them set up a firm foundation and now they are a fantastic, big, productive group.

JRT: I understand you were even recognized by the king of Nepal for your work there.

BT: I met him just months before he was assassinated by his son. The king heard about our work, and he invited us — my Nepali partner and me — to his study. The king said to me, “I really like what you’re doing, and I want you to tell me what I can do to help you.” And then he said to my Nepali colleague, “If I forget, you must nudge me.” Then my Nepali friend dropped to his knee. It was so moving. We felt we had finally met someone who could support us. Just months after that, the king was killed.

JRT: Where have you experienced some of the toughest challenges?

BT: What we’re encountering now in West Sumatra is baffling. The local, provincial and national government know that in Padang — we’re talking about a city that is just southeast of the great tsunami of 2004 — when the expected tsunami occurs, half of the population is projected to die. That’s half of 900,000 people. They’ve been told that this tsunami could occur tomorrow, but it almost certainly will occur in the lifetime of the children now living in their city. But, despite this, not enough is being done, fast enough. The city needs a Churchill, not a Chamberlain.

The people in the area know that the tsunami will arrive about 30 minutes after the expected earthquake, so whenever the residents feel strong shaking, they all get in their cars and rush to their children’s schools and it’s a traffic jam. The vast majority will never make it to safe ground before a tsunami arrives.

villagers practice molding adobe bricks. Credit: David Hermoza, courtesy of GeoHazards International.

JRT: What do you hope to do there?

BT: We are working to build a Tsunami Evacuation Park, which is a manmade hill that will have something like a soccer field on top. This is one of the many tactics used by the Japanese that are responsible for their losing only 3 percent of the population that was inundated following the 2011 quake and tsunami.

This hill, we think, will have a capacity of 20,000 people. If we build it, strategically placed by a busy street, the next time there’s an earthquake in Padang, people will be stuck on the street and see this hill seven meters in height, out of the tsunami zone, and they’ll say, “I could just park my car and go up there and be safe.” Of course, we will train teachers and students in local schools to evacuate to there. And kids will be using the soccer field every day. We hope such a structure will encourage the government to build more of these.

I just see the government officials as, for some reason, frozen. We’ve been mainly supported in this effort by [reinsurance and financial group] Swiss Re, which I gratefully acknowledge.

__JRT: How do you spend your free time? __

BT: My main hobby is something called C.R.A.S.H.-B. It’s a rowing competition on rowing machines. There’s an international competition every year in Boston, where people sit on these rowing machines. You all race and it’s for different genders and different age groups, and I spend whatever free time I have to stay in shape for that.

JRT: When you eventually retire, how do you plan to spend your time?

BT: I hope to leave this organization strong, in good hands with a powerful board of trustees and a powerful staff, continuing to evolve and doing things that I can’t even imagine.

Then I dream of rowing on a Swiss lake.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.