by Mary Caperton Morton Friday, March 6, 2015

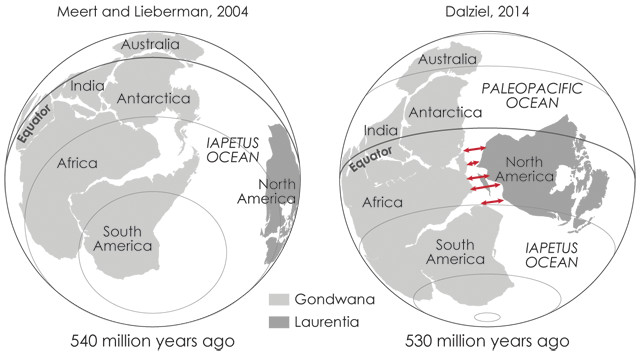

The location of the continents at the beginning of the Cambrian Period has long been difficult to resolve. Whereas one model based on paleomagnetism, for example, suggested that the oceanic separation between Laurentia and Gondwana was already fairly wide by that time (left), a new study based on geologic data proposes that the opening between the landmasses (red arrows) only initiated shortly before the Cambrian Explosion 530 million years ago (right). Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI.

Roughly 530 million years ago, Earth’s living cast of characters ballooned as a surge of evolutionary development led to the sudden appearance of almost all modern animal groups. Fossils from this period document the change in species, but the geologic, atmospheric and/or biotic factors that may have caused the radiation remain mysterious. Now, a new study suggests that massive changes in the positions of the continents may have played a significant role in sparking the Cambrian Explosion.

Reconstructing the arrangement of continents before the formation of Pangea about 300 million years ago is difficult due to the lack of ancient vestiges of ocean floor, which rarely lasts more than 200 million years before being recycled in subduction zones. “Data from modern ocean floors tell us exactly how to reconstruct Pangea, but before that, we don’t have that luxury,” says Ian Dalziel, a paleogeographer at the University of Texas at Austin and author of the new study, published in Geology.

Paleomagnetic data, which record the orientation of magnetic minerals in rocks with respect to Earth’s geomagnetic field when the rocks form, work like a compass to give researchers indications of continental paleolatitudes and orientations. But determining paleolongitudes is far trickier. Scientists must rely on geological features and fossils shared across continents, along with ages and isotopic compositions of rocks, to position past continents on the globe.

“Cambrian paleogeography is a very complicated four-dimensional puzzle with a lot of uncertainty,” Dalziel says. To solve it, Dalziel made the first attempt to integrate geological evidence, including stratigraphic and fossil evidence, from five present-day continents — Africa, Antarctica, Australia, North America and South America — to piece together the paleogeography at the time of the Cambrian Explosion.

Previous reconstructions of global geography during the early Cambrian show that the ancient continent of Laurentia — the ancestral core of North America — had already separated from the supercontinent Gondwana at this time. However, Dalziel’s results suggest that Laurentia was still attached to Gondwana at the beginning of the Cambrian Period, about 540 million years ago.

He proposes that the development of a deep oceanic gateway between the Pacific and Iapetus oceans then isolated Laurentia sometime shortly before 530 million years ago.

This geographic makeover “triggered the spreading of shallow ocean water across the continents, which is clearly tied in time and space to the sudden explosion of multicellular and hard-shelled life on the planet,” Dalziel says. “Suddenly, the seas are rising and washing over the continents and providing a host of new ecological niches for life to occupy.”

The relatively sudden geologic and geographic changes probably also led to changes in ocean circulation and chemistry — including increasing oxygen concentrations and influxes of iron, calcium and phosphorus due to erosion of the continents by the rising seas — perhaps allowing more complex lifeforms to evolve, he says.

The exact timing of the oceanic opening — whether it occurred at the right time to trigger the Cambrian Explosion, or much earlier — remains in question, however. Dalziel’s story makes sense, but his models don’t match up with existing paleomagnetic data, says Joe Meert, is problematic because a lot of good paleomagnetic data tell us that this ocean was already pretty wide by that time," he says.

Meert acknowledges that the time period is notoriously difficult to model: “Paleogeographers are barely comfortable with Cambrian reconstructions. There is some wiggle room, but I think [Dalziel’s] model is too far off the mark.”

Dalziel says he plans to continue collecting geologic data from all over the world, while also working with researchers who study paleomagnetism to refine his model and better reconcile the pictures presented by the geologic and paleomagnetic data. “The relationship [between the two] is not quite there yet,” he says. “A lot of time has passed since the Cambrian. It’s not an easy period to resolve.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.