by Mary Caperton Morton Thursday, July 14, 2016

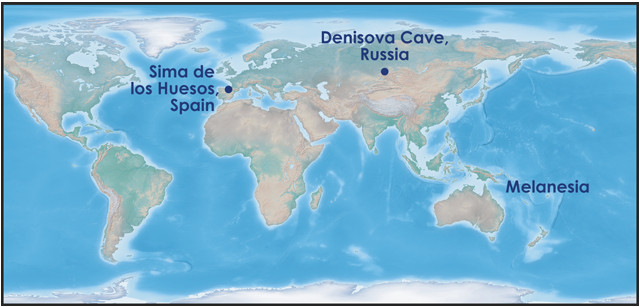

Denisovans were first identified from a 41,000-year-old finger bone found in a cave in Siberia. In two new studies, traces of Denisovan DNA have been found in modern Melanesians and in 430,000-year-old remains at the Sima de los Huesos site in Spain. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

In the time that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals were coexisting — and interbreeding — there was at least one more human species on the landscape, the Denisovans. First identified from a 41,000-year-old finger bone found in a cave in Siberia, the Denisovans are now thought to have been widespread around Eurasia. In two new studies, scientists have shed additional light on the relationship of Denisovans to other humans, finding new traces of Denisovan DNA in ancient and modern genomes.

“Denisovans are the only species of archaic humans about whom we know less from fossil evidence and more from where their genes show up in modern humans,” said Joshua Akey, of the University of Washington (UW), a co-author of one of the new studies, in a statement. Substantial amounts of Denisovan DNA have been detected in the genomes of a handful of modern humans so far; the new study, published in Science, increases the database by running whole-genome sequences of 1,523 geographically diverse individuals.

The researchers found that Denisovan DNA makes up between 2 and 4 percent of the genomes of modern Melanesians, while people from other regions carry smaller amounts of Denisovan DNA. The findings reflect the Denisovans' widespread population, said lead author Benjamin Vernot, also at UW. “I think that people (and Neanderthals and Denisovans) liked to wander,” Vernot said, and “studies like this can help us track where they wandered.”

Another new study, published in Nature, focused on ancient DNA recovered from 430,000-year-old Middle Pleistocene hominins found at the Sima de los Huesos locality in northern Spain. A team led by Matthias Meyer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany analyzed both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA samples recovered from the site. The nuclear DNA indicates that the Sima de los Huesos hominins were more closely related to Neanderthals, despite the mitochondrial DNA resembling that of Denisovans.

The apparent discrepancy is probably due to the early age of the Sima de los Huesos specimens, which likely represent an early stage of Neanderthals, according to the researchers. The mitochondrial DNA characteristic of other Late Pleistocene Neanderthals may have been acquired at a later time, the researchers suggested. “Retrieval of additional mitochondrial and nuclear DNA from Middle Pleistocene fossils could help to further clarify the evolutionary relationship between Middle and Late Pleistocene hominins in Eurasia,” the team wrote.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.