by Terri Cook Wednesday, December 3, 2014

Members of GSA at a formal banquet held during the 1940 annual meeting in Austin, Texas. Credit: Courtesy of GSA.

When the Geological Society of America (GSA) held its first organizational meeting in December 1888, there were only about 200 geologists in North America. Today, as GSA celebrates its 125th anniversary, the organization has evolved into one of the world’s largest societies devoted exclusively to geology, representing more than 25,000 members — researchers, students, teachers and industry professionals with interests spanning the geosciences — in 107 countries.

GSA is an offspring of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), which itself grew out of the Association of American Geologists and Naturalists in 1848 after the association’s scientific interests diversified. Discussion of a split from AAAS began in earnest in 1881, when a small band of geologists gathered at the annual meeting to consider establishing an independent geological society.

Similar informal gatherings took place in 1882 and 1883, but the establishment of GSA was delayed, according to Edwin Eckel, author of “The Geological Society of America: Life History of a Learned Society,” by political infighting as well as competing interest in forming an International Congress of Geologists.

The geologists wanted to establish a separate organization because geology was rapidly growing as a science, but they were also dissatisfied with AAAS. AAAS meetings were more social than scientific, they said, and were not well attended by geologists because they were held during the summer field season. However, the most compelling reason for forming an independent society was to provide a forum for publishing. “In those days, there were very few journals,” says Suzanne Mahlburg Kay, GSA’s current president and a professor of geology at Cornell University.

The proposed break from AAAS at first concerned many geologists, but by 1888, much of the opposition had dissipated. A formal call to organize GSA appeared in the June issue of the journal American Geologist. Within a few months, the fledgling society had garnered the requisite 100 applicants for membership and a provisional constitution and bylaws were circulated. A formal organizational meeting was set for Dec. 27, 1888, at Cornell.

By all accounts, the inaugural meeting of the American Geological Society, attended by 12 of the original founders plus about a dozen new members, ran smoothly. The members adopted a constitution, appointed committees, and elected the society’s initial officers, including the first president, James Hall. Hall had not been instrumental in organizing the society, but he was a prominent New York geologist and paleontologist who was the first to identify the biological origins of stromatolites. “They wanted to bring global prominence to the society,” Kay says, “so they looked for someone who was one of the big names at the time.” At the 1889 meeting, the name was changed to the Geological Society of America and technical sessions were held for the first time. The society also elected its first female fellow, paleontologist Mary Emilee Holmes, the first American woman to receive a doctorate in geology.

Members of GSA at a formal banquet held during the 1940 annual meeting in Austin, Texas. Credit: Courtesy of GSA. Credit: GSA.

From its founding to the present day, the society’s primary mission has been the promotion of the science of geology. It serves this function primarily through its extensive publications such as GSA Bulletin, which has been published continuously since February 1890, as well as research grants and meetings. GSA is subdivided geographically into seven sections, each of which has its own management board and hosts an annual spring meeting. In addition, members are free to join any of the society’s 17 divisions, which link members with similar interests such as geoarchaeology or planetary geology.

Regular meetings are one of GSA’s hallmarks. “Provision of the facilities for these personal contacts,” wrote Eckel, “is probably the society’s greatest contribution to the advancement of the science.” These range from the large, annual October gathering to smaller sectional meetings, as well as the specialized Penrose Conferences, which assemble a small but diverse group of researchers to engage on a specific geologic topic.

Jack Hess, GSA’s executive director, and Kay agree that despite all the technological advances in communication, none can replace the personal contact found at a GSA meeting. “One of the interesting statistics about our meetings,” Hess says, “is that we have almost twice as many attendees as abstracts, whereas meetings for comparable societies are much closer to a one-to-one ratio. That says there’s something different about a GSA meeting: People are coming to network and to interact as well as to present papers.”

When the society was established, dues were set at $10 per year (the equivalent of about $250 today) — an exorbitant rate at that time — in order to discourage applications from nongeologists, according to Eckel. Today, the society strives to keep annual dues low, including by implementing a three-tiered pricing structure that encourages membership from students and geologists in lower-income countries. The society relies instead upon revenue from publications and meetings to balance its budget, Kay says.

In 1931, longtime member and past officer R.A.F. Penrose bequeathed half of his fortune, nearly $4 million, to GSA" “Other than the founding,” wrote Eckel, “the acquisition of the Penrose fortune was surely the most important single event in GSA’s entire history.” Until the bequest, the society had depended solely upon subscriptions and dues to balance its budget; suddenly, it had a fortune at its disposal, and there were many necessary adjustments — and some growing pains — that had to be resolved.

For example, at the time of the bequest, GSA did not have a permanent home. For the society’s first 42 years, its “headquarters” consisted of a corner of the current GSA secretary’s office, most often at a university in New York City. In 1930, GSA moved into a two-room suite at Columbia University, which easily housed all the society’s property — a typewriter, an Addressograph (an address-stamping machine patented in 1896), some files and a photograph collection."

Shortly after Penrose’s death in 1931, Columbia University offered GSA the use of one of its residential buildings, which the society renovated and furnished with items from Penrose’s estate. Built of Triassic-aged sandstone with fossil-studded limestone trim and slate steps, GSA House accommodated the society’s offices as well as several bedrooms for visiting members. The society remained in the house until 1963, when GSA purchased a building on East 46th Street in New York City. Just a few years later, facing the ever-increasing cost of operating in New York City, incl"ding the difficulty in finding and retaining qualified staff who could afford to live there, the council voted to relocate its headquarters to Colorado. The executive secretary selected the town of Boulder for its proximity to the University of Colorado, its strong pool of employees and its distance, wrote Eckel, “from potentially undue influence of the burgeoning U.S. Geological Survey” located in Denver.

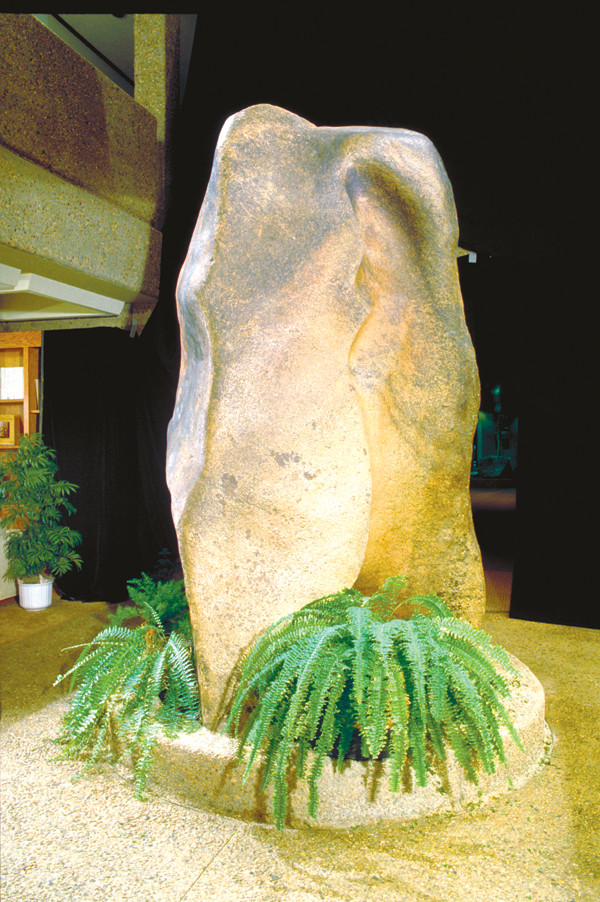

In 1967, GSA moved into temporary offices in downtown Boulder, and resided there while building a new headquarters on the northern edge of town, which the society still calls home today. The concrete and glass building’s open structure was designed to bring nature inside, emphasizing geology as an outdoor science. The facility, which is open to the public for tours, contains a large collection of geological specimens, including dinosaur footprints and other fossils, as well as objects of geological art. At the formal dedication in 1972, then-president Luna Leopold said, “all concerned wanted something as beautiful as we could obtain … something that we hoped would constantly remind all viewers of the grace and symmetry exhibited in earth materials.”

More than 80 years after the Penrose bequest, the funding is still very important to GSA. According to Hess, the proceeds from this gift have enabled the society to take on new initiatives, such as opening an office in Washington, D.C., in 2007, when the society decided to work more directly on government affairs.

This 3-meter-high, 7-metric-ton Silver Plume granite boulder from the Big Thompson River greets visitors in the lobby atrium of GSA's headquarters. Credit: GSA.

To celebrate the society’s 100th anniversary in 1988, GSA undertook the publication of the Decade of North American Geology, a series of 27 volumes summarizing what was then known about the geology of North America after the plate tectonics revolution. “It was a massive project, a real survey of the geology of the country,” Kay says, “and although 25 years have passed, people are still using the papers and field trip guides.” In addition, Hess says, “the effort to raise the funds to publish that volume was really the start of the GSA Foundation,” which continues to raise money to support many of the society’s objectives.

In contrast, the 125th anniversary has emphasized the last 50 years. The motto of the anniversary celebration is “Celebrating Advances in Geoscience: Our science, our societal impact, and our unique thought processes.”

“Twenty-five years ago, you didn’t hear people in our science talking about societal impacts, or even government affairs or public policy kinds of things,” Hess says. In the last 10 years, GSA has added two new divisions — Geology and Health, and Geology and Society. “So I’ve seen the interest in the society growing at the intersection of geology and policy and sustainability and society,” he says. “That’s where part of that motto comes from as we look forward. It’s a significant piece of the strategic plan, too.”

The 125th annual meeting, held in Denver in October, set society records both for the number of abstracts submitted as well as the number of participants. In addition to the diverse technical program, the meeting featured a number of special celebratory touches, including a commemorative beer bottled by Left Hand Brewing Company of Longmont, Colo. — named Field Assistant Ale — as well as two 125th anniversary wines, a 2010 chardonnay and an estate-bottled 2009 merlot from California’s Lava Cap Winery, which was founded by geologist Davy Jones. “The wine has a connection,” Kay says. “It wasn’t something somebody in headquarters dreamed up. The idea came from the membership.”

Another unique part of the program was a live performance by the Boulder Philharmonic Orchestra of “Symphony No. 1: Formations,” an original symphony composed by University of Colorado music professor Jeffrey Nytch, who trained as a geologist. The symphony was inspired by the geology of the Rocky Mountain region.

Looking to the future, the society is keen to expand its international partnerships. During her one-year term as GSA president, Kay is organizing a field forum in Cuba and laying the groundwork for co-hosting a meeting in Africa in the next few years. GSA is simultaneously expanding its “GeoVentures” travel programs, its field offerings for K-12 teachers and its informal educational programs, such as EarthCache.

“I think this meeting will set a new base from which the society can grow in the future,” Hess says, adding that he believes that technology has been a driving force for the science of geology. Kay agrees. As she tells her students in the field, “you’re looking at the same rocks that somebody looked at 100 years ago, but you’re looking at them from a totally different perspective.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.