by Mary Caperton Morton Monday, June 30, 2014

Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI

As a leading researcher in the field of atmospheric science, University of Washington scientist Dan Jaffe had never had trouble securing funding for his work on airborne pollutants. Over the past 20 years, he has been awarded more than $7 million dollars in grants from multiple government agencies, from NOAA and NASA, to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF). That all changed when he wanted to study the effects of increased coal-train travel through his home state of Washington.

With coal use declining in the U.S., many companies are seeking to ship their products overseas, and in 2012 and 2013, four new proposals were submitted to increase rail shipments of coal from Montana and Wyoming to ports in Washington and Oregon for export to Asian markets.

“As part of the required environmental impact report, the Army Corps of Engineers agreed to study any issues around the port, but they weren’t going to go any broader,” Jaffe says.

“So I went to the usual places — EPA, NSF and various state and local agencies — and pitched the coal-train pollution project as an important issue involving the transport of hundreds of millions of tons of coal a year.”

Much to his frustration, all of his proposals were turned down. “These agencies essentially said, ‘This is really political, a big hot potato, it’s outside of our jurisdiction and it’s not our responsibility.’ It was really frustrating and we almost gave up, but then somebody asked, ‘What about crowdfunding?'”

So, Jaffe turned to Microryza.com, a crowdfunding platform much like Kickstarter that caters to scientists looking to fund scientific research. Soon after launching his “Do coal and diesel trains make for unhealthy air?” campaign, the Seattle Times newspaper ran a story about Jaffe’s funding plight and, within a week, the $18,000 coal-train pollution project was fully funded. By the end of the month-long funding period, more than 250 people had kicked in a total of more than $20,000.

“We were able to conduct a rigorous scientific study — not a policy piece or a political study — and ask some very specific scientific questions about the impacts of diesel and coal dust for people who live near the train tracks,” he says.

Because the study was so enthusiastically funded by the general public, Jaffe felt it was important to publish the results in an open-access journal. In January 2014, the study was released in Atmospheric Pollution Research, with a special nod in the acknowledgments section to the donors of Microryza.

“This really goes to show that the public is willing to help support science,” Jaffe says. “Of course, crowdfunding is never going to replace the big pots of money available from the NSF, but it certainly has its place.”

In April 2009, three New York City-based entrepreneurs launched Kickstarter, a crowdfunding platform designed to give artists and innovators a way to solicit funding from individual donors for creative projects. Since then, more than 6 million people have pledged more than $1 billion to fund 63,000 different campaigns.

Kickstarter campaigns attempt to entice donors with a webpage that introduces and explains the project, outlines the goals, details any potential risks, and challenges and presents a mandatory video. Campaigns must meet their pre-set funding goal by the end of their 30- or 60-day funding window or they fail and receive no funding and the money is returned to the donors. If they are successful, Kickstarter keeps a 5 percent fee.

“Kickstarter was started with a focus on the arts, but over time people have come up with different ways to use it that we didn’t anticipate,” says David Gallagher, a communications director at Kickstarter, where the categories include art, dance, fashion, games, music, publishing and technology. “We don’t have a science category, but that doesn’t mean people haven’t found creative ways to fit science projects into the model.”

One project submitted under the technology category — “KickSat: Your personal spacecraft in space!” — proposed to launch nanosatellites into space.

“We turned to Kickstarter really out of desperation,” says Zac Manchester, a graduate student in aerospace engineering at Cornell University. With a working prototype already in hand, Manchester had a matter of months to produce a hundred of the miniature “sprite” satellites in time to catch a ride to space with NASA’s ELaNA: Educational Launch of Nanosatellites program, which gives university satellites a free ride into orbit.

HyperV Technologies used Kickstarter to build a plasma jet thruster for use in spacecraft. The developers gave their backers stickers, T-shirts and a behind-the-scenes look at how plasma jet thrusters are built. Credit: HyperV Technologies.

“We’d gotten funding through various grants and agencies previously, but that money was already allocated for other projects. When this opportunity for a free ride came up, we needed money fast,” he says.

Manchester and his team created a Kickstarter campaign seeking $30,000 to pay for the hardware they needed. In exchange for funding their project, they offered backers who pledged at least $75 a replica sprite to keep. Those who pledged $300 or more got their initials on their very own sprite spacecraft in space. By the end of the 60-day funding period, donors had pledged nearly $75,000.

“One of the reasons I think our project was so successful was that there was a sense of personal ownership. Donors got their own little satellite,” Manchester says.

But not every science project comes with tangible rewards for backers. A project seeking funding to build a new type of plasma jet thruster for use in spacecraft couldn’t offer people their very own thruster, so instead they gave their backers stickers, T-shirts and a behind-the-scenes look at how plasma jet thrusters are invented.

“We set out to create an experience for people,” says Chris Faranetta of HyperV Technologies, based in Chantilly, Va., who ran the campaign. “Our product was taking people along on the journey of building the thruster, testing it and then inviting people to witness the climactic firing event.”

By the end of their 30-day funding period, 1,101 people from around the world pledged more than $72,000. “Most of our donors seemed to be people who like technology and wanted to do something to help further space exploration. It was amazing how enthusiastic people were,” he says.

Throughout the process, Faranetta and colleagues posted regular updates, technical information and videos of the development process. “We had people touring the lab and attending tests. It was really very exciting, not just for the backers, but also for us, having all these fans.”

Crowdfunding platforms are ripe for fostering more communication between scientists and the general public, says Jai Ranganathan, a co-founder of SciFundChallenge.org, an organization that trains and encourages scientists to engage in crowdfunding through the platform RocketHub.com.

“Our interest in crowdfunding really came from our mission to close the gap between scientists and society. You can’t do crowdfunding unless you’re willing to engage with the public. Any cash generated comes second to the public outreach aspect, which is really priceless,” he says.

Surveys conducted by NSF indicate that the American public generally has a positive view of science, but that scientific literacy — defined as “a good understanding of basic scientific terms, concepts, and facts; an ability to comprehend how science generates and assesses evidence; and a capacity to distinguish science from pseudoscience” — is low overall. For example, less than a third of Americans surveyed responded correctly to questions about how scientific experiments are conducted with controls and variables, with nearly 20 percent failing all the questions.

“The goal is a better understanding about how science works — the scientific method and the process of discovery,” Ranganathan says. “If people follow a scientist over the course of a year, they’ll see how scientific discovery happens and hopefully be able to better recognize junk science.”

Communication between scientists and funders can take many forms, including blog posts, Twitter updates, live webcams, all avenues supported by most crowdfunding platforms. “Pick the style of engagement you like and do it on a consistent basis. That’s the secret to successful crowdfunding,” Ranganathan says.

The two biggest crowdfunding platforms, Kickstarter and Indiegogo, raise hundreds of millions of dollars for a broad range of projects, but other alternative platforms have been popping up by the hundreds, catering to many different sectors, including real estate, investing, small businesses, charities and science.

“At this stage, the number one hurdle is awareness. There are a whole lot of crowdfunding platforms out there right now, but time will tell which will stay and which will go,” says David Marlett, executive director of the National Crowdfunding Association (NLCFA), a trade association geared toward educating fundraisers and investors on the intricacies of crowd funding. “The name of the game is eyeballs. If the eyeballs are there, the funding is there.”

At one time, more than 30 science-specific platforms were in the works, but only a third have gone live and among those, two major players remain: RocketHub.com and Experiment.com (formerly called Microryza). Both operate on similar principles to Kickstarter, with a few variations.

Experiment.com eliminates the perks offered to backers on Kickstarter, in an effort to channel more time and money directly into the research. “Early on, we realized that the reasons people would choose to fund science aren’t the same reasons that people fund creative projects,” says Denny Luan, a co-founder of Experiment.com. “The natural output of most scientific research isn’t usually a product that can be shared. We didn’t want to have scientists offering T-shirts or mugs or keychains as rewards; instead we encourage them to make participation in the scientific process itself the reward.”

RocketHub keeps the reward system, but encourages scientists to think outside the box for their perks. “Creative rewards are really important,” says Alon Hillel-Tuch, one of the co-founders of RocketHub. Sometimes authors will offer to list backers’ names in the acknowledgment section of their papers. Others offer lab tours, private lectures or special consults. Some archaeologists and paleontologists even offer to take backers into the field on excavations.

Even when they are offered perks, many donors turn them down. “We found the reward scheme wasn’t as important as we initially thought,” says David Kipping, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., who ran a campaign on the now defunct Petridish.org to raise $10,000 to study exomoons. “Lots of people said they didn’t want the reward, they just wanted to contribute. It was really inspiring and refreshing to have that kind of support.”

Another project funded through Petridish.org — to excavate whale bones from a quarry in Virginia — offered specimen casts to some high-dollar donors. “We found about half the donors declined the perks because they wanted the money to go toward the dig, not toward shipping,” says Alton Dooley, curator of paleontology at the Virginia Museum of Natural History in Martinsville. “We did have one donor join us on the dig, but that was a fairly easy perk to fulfill. He was actually a great help!”

While some might worry that crowdfunding will favor “crowd-pleasing research,” crowdfunding success seems to have less to do with the project itself than the way it’s presented, Luan says. “There is no one specific archetype of a successful crowdfunding project. That’s one of the best things about seeking funding this way: There’s a lot of flexibility in how these stories are told.”

Because successful crowdfunding is so dependent on telling a good story, campaigns with a face tend to do better than those run by a group or an organization, Hillel-Tuch says. “Funders really relate to somebody who can communicate a lifelong passion for answering mysterious questions.”

If a researcher can put together a good story, even esoteric projects can get funded. “We had a microbiologist in New Zealand who was studying the evolution of E. coli in mouse guts,” Ranganathan says. “There’s nothing sexy about mouse guts, but she was such a gifted communicator that she got her project funded.”

Crowdfunding takes a different skill set than applying for grants, and is often a faster process — most successful projects receive funding within two months as opposed to nine months to a year for NSF grants — but it’s not necessarily easier. “Crowdfunding is an emotionally, socially and time-intensive process,” Hillel-Tuch says. “It’s a mistake to think it’s easier than grant writing. Crowdfunding is a full-court press for 30 days, then you have to fulfill all your campaign promises and stay in touch with your donors.”

“Crowdfunding is a lot of work — a full-time job, more than 40 hours a week, for several months,” Manchester says. “You don’t just load your campaign page and walk away. There are a lot of pieces to the puzzle that you don’t know you’re going to have to deal with before you begin, like torrents of questions and tax issues. We did a lot of flying by the seat of our pants.”

When a researcher applies for a grant from NSF, the application goes through a merit review process — which includes close examination by panels of independent scientists, engineers and educators who are experts in relevant fields. The goal is to select the most deserving projects. With crowdfunding, anybody can ask for money for anything.

To help filter out off-the-wall projects, most platforms have a review process, with some being more rigorous than others. Kickstarter goes easy on vetting new projects. “We’re not screening for quality or whether you can actually pull it off,” Gallagher says. “We just make sure it’s a project that fits into our categories. Generally, we approve a lot more projects than we reject.”

But that lack of initial oversight can be a turnoff to researchers. “I ended up using Petridish because I felt their project approval process gave more accountability to my project,” says Ulyana Nadia Horodyskyj, a graduate student at the University of Colorado at Boulder who has funded two Himalayan expeditions to study glaciers using crowdfunding.

“Scientists are so concerned about reputation that even a whiff of disreputability will drive them away,” Ranganathan says. “This is why having a review process to vet potential projects is important. We don’t want to see people proposing to do ridiculous things, like go search for living dinosaurs in the jungle.”

But even if less-than-reputable projects do get funded, scientific results will need to undergo peer review before being published, Jaffe says. “Peer review is the gold standard in science. At the end of the day, a journal will accept or reject [the science] so you still have that rigor.”

Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI

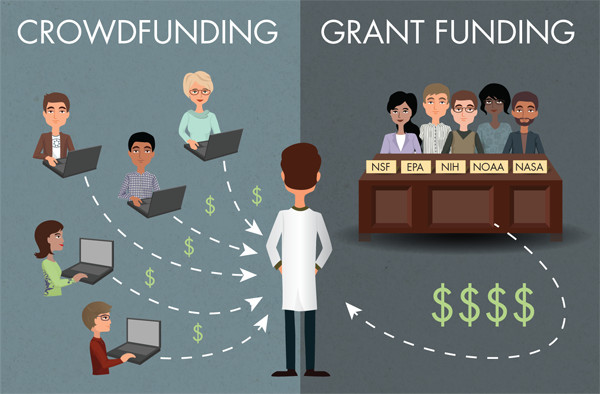

Scientific research has traditionally been funded by grants from various governmental agencies like NOAA, NASA, EPA, NSF and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), along with funding from universities, corporations and private foundations.

But while billions of dollars are up for grabs — NSF alone has an annual budget of more than $7 billion — competition for grants is high and money is often given out in large chunks to big research labs, leaving smaller, shorter-term projects in the lurch.

“I think it’s fair to say that the level of competition for grant money has gone up in the past few years,” says Kevin Crowston, a program director at NSF, based in Arlington, Va. “The number of grant applications has been going up steadily, as has the [NSF’s] budget, but not as quickly.”

Each year, NSF receives about 40,000 applications for grant money and usually rewards about a quarter of those projects. The average grant awarded in 2012 was $165,000, a number that favors large multiyear research projects. These can take between six months to a year to be funded.

“If you’re looking for a few thousand dollars to run a short-term project, NSF doesn’t have a mechanism for that model of funding,” Crowston says. “We’re working on a very different scale from most of these crowdfunding campaigns.” For now, the NSF has no plans to adapt or adopt the crowdfunding model. “The NSF has its role and that’s not going to change,” Crowston says.

A few crowdfunding campaigns have gone viral and raised hundreds of thousands of dollars, but $10,000 or less is a more reasonable goal, Luan says.

“Crowdfunding is never going to replace NIH or NSF in terms of sheer dollars,” Luan says. “But we’ve created a sweet spot. Projects that need some seed money to try a new idea or collect preliminary data can really benefit. Then, once you prove your concept, you might apply for a larger grant,” he says. “Our goal is to prove ourselves not as a replacement for NSF but as an alternative funding source.”

Crowdfunding can also be ideal for student-run projects. As a graduate student in archaeology at Florida State University, Allison Smith studies the hydraulics of ancient Roman bathhouses, but fieldwork in Italy is expensive.

“At this [early] stage in my career, it’s difficult to get funding from traditional sources,” she says. But Smith was able to pay for her travel expenses by running a $2,000 campaign on Experiment.com. “I found that there were a lot of people on Experiment specifically looking to fund student research. It’s an incredibly supportive community.”

Some universities have taken to working directly with various crowdfunding platforms to encourage students to take advantage of public largesse. “Universities are ripe for crowdfunding because they’re full of creative, innovative people who need funding,” Hillel-Tuch says. But crowdfunding in the university setting can come with its own unique set of challenges, including administrative and tax hurdles. “At RocketHub, we’ve been focusing on relieving these road blocks by giving schools the tools that they need to green light great projects,” he says.

For example, RocketHub can send money to a department instead of directly to the student, which often helps simplify tax issues. That’s not the case with Kickstarter, which insists on wiring money to personal bank accounts. “I didn’t expect to have to deal with tax-code issues when I did my Kickstarter campaign,” Manchester says, “but as a poor graduate student, having $75,000 suddenly deposited into my personal bank account was pretty crazy. I had to figure out what to do with it without running afoul of the IRS.”

Campaigns run through a university-curated page also have a slightly higher rate of success, says the NLCFA’s Marlett, who also works at the University of Texas at Dallas, facilitating the school’s university-curated crowdfunding platform.

“University-curated crowdfunding has a 50 percent success rate,” he says, slightly higher than Kickstarter’s average of 43 percent. “Big schools have a lot of eyeballs and a lot of people with a vested interest in supporting the school. When it comes to finding a crowd, alumni loyalty is a powerful resource.”

Since Kickstarter launched in 2009, it has redefined how creative projects get funded. Time will tell whether crowdfunding for scientific research takes off as well.

The next step will require more widespread awareness of crowdfunding as a viable and respectable alternative for funding scientific research, Marlett says.

“In general, the culture of science moves incredibly slowly. The current granting model hasn’t changed in decades,” Ranganathan says. “But people are intrigued by crowdfunding, and it’s inspiring a whole new level of public outreach that will hopefully lead to more scientific transparency, literacy and engagement.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.