by Maddie Bender Monday, February 4, 2019

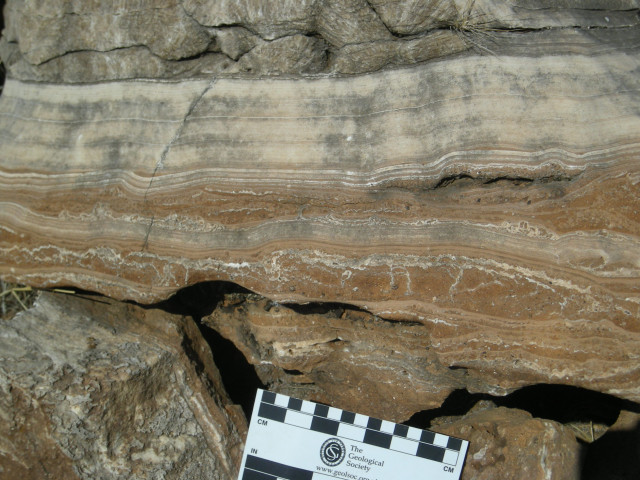

A light-colored flowstone deposit lies atop lithified red sediments in a South African cave were hominin fossils were found. Researchers dated such flowstones to constrain the ages of fossils found in adjacent sedimentary layers. Credit: Robyn Pickering

Robyn Pickering was taught as an undergraduate about a collection of limestone caves in northern South Africa known collectively as the Cradle of Humankind for the trove of early hominin fossils discovered there. She learned that, unlike hominin fossils unearthed in East Africa, whose ages have been constrained by dating the surrounding layers of volcanic ash, the fossils in the Cradle — including well-preserved specimens of Australopithecus africanus and the recently discovered Homo naledi, among others — were impossible to date independently.

Now, Pickering, an isotope geochemist at the University of Cape Town, and her colleagues have figured out a way to date the South African fossils after all. In a recent study published in Nature, the researchers report ages for flowstones — horizontal deposits of calcium carbonate that form natural cements on cave floors — across eight caves in the Cradle of Humankind. The flowstones sandwich fossil-bearing sediment layers, allowing age ranges for the fossils to be determined.

Previously, the ages of hominin fossils found in the South African caves were estimated by comparing animal bones found nearby to similar-looking ones in East Africa whose ages had been reliably determined. This kind of relative dating comes with more uncertainty and relies upon an assumption that evolution in East Africa was occurring at the same time and rate as it was in South Africa, according to Bernard Wood, a paleoanthropologist at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., who was not involved in the study.

The arid landscape of the Cradle of Humankind today was wetter and more vegetated at times in past, between 3.2 million and 1.3 million years ago, according to the new study. Credit: Robyn Pickering

“This dataset brings the South African record back into the story [of paleoanthropology], back into the conversation, because the caves have their own ages — they’re not relative ages and they’re not compared to East Africa,” Pickering says.

To date the flowstones, Pickering and her team applied uranium-lead dating, a technique that is typically used to date rocks that are hundreds of millions to billions of years old, while the flowstones were mere millions. The work was time-consuming, representing more than a decade’s worth of research, and exacting: There is more lead on a person’s fingerprint than in the flowstone samples, Pickering says. This meant the researchers had to take precautions to avoid contaminating samples, including working in a lab with positive pressure and filtered air.

In the end, their analyses showed that the Cradle of Humankind flowstones dated to several short intervals between 3.2 million and 1.3 million years ago. The flowstones would have formed when the prevailing regional climate was wet and flowing water was abundant, the researchers suggested, and likely when the caves were covered with vegetation and closed off from the outside world, allowing the calcium carbonate layers to form uninhibited. With dates established for the flowstones, it’s possible to constrain the ages of hominin fossils preserved in sediment layers that would have been deposited when the caves were open during relatively dry and dusty climates.

David Strait, a paleoanthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis and a co-author of the research, says the discovery of the alternating layers deposited during wet and dry times reveals gaps in the South African fossil record that were previously unknown.

“The wet periods give us the flowstones, which are wonderful because they let us know how old parts of the cave are, but they also limit our ability to see what’s happening in the past” at those times, because no fossils were preserved when the flowstones were forming, Strait says. “We’re only getting a window into what the landscape and faunal community were like during relatively dry conditions.”

Despite the limitation, the new method of dating flowstones — deposits that are ubiquitous in caves and that were once thought to be a nuisance — is an important development, Wood says. Having a means to absolutely date fossils in the Cradle of Humankind augments the fossils’ scientific value, he says.

After developing the uranium-lead method for flowstones, Pickering says she now has her sights set on doing the same for calcrete, calcium carbonate crust that’s found in soils at many open-air archaeological sites in South Africa that have not yet been dated. “Everyone says [calcrete] is impossible to date,” she says, “which makes it irresistible to me.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.