by Glenn Branch Friday, August 31, 2018

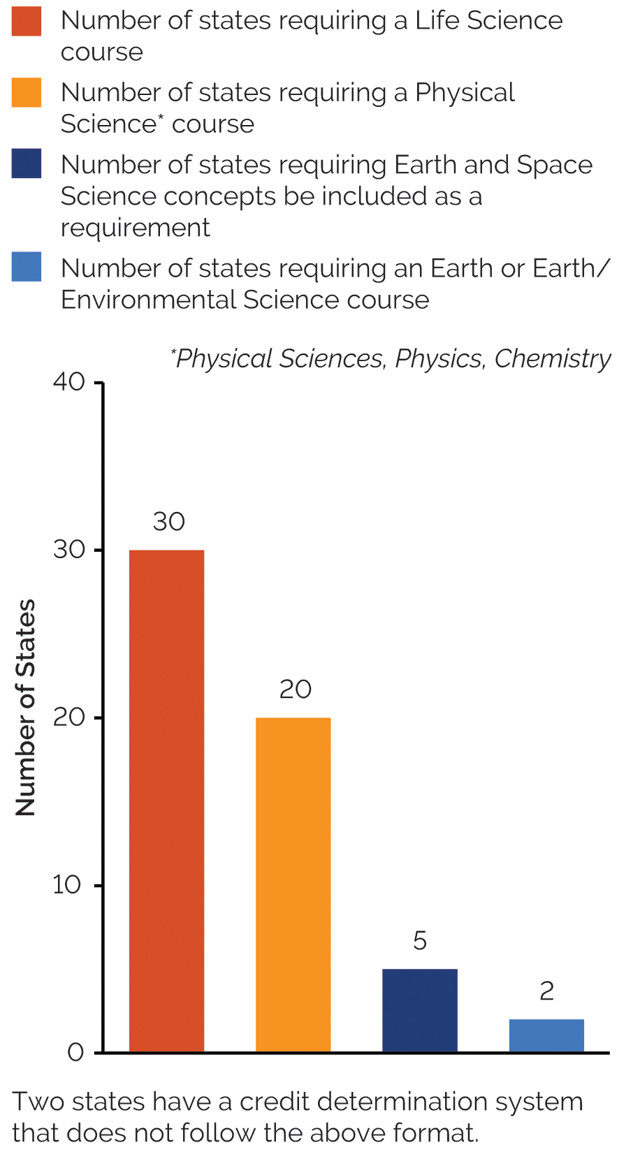

Climate science education often falls through the cracks in K–12 curricula. Earth and environmental science classes, in which climate science is most likely to be taught, are not required in most states. Thus, the incentive to teach those classes is absent. Credit: ©American Geosciences Institute, 2015.

Climate change was in the national spotlight this past summer when The New York Times Magazine devoted its entire Aug. 5, 2018, issue — except for the beloved puzzle section — to Nathaniel Rich’s article “Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change.” As it happens, “Losing Earth” added a puzzle of its own. Late in his 30,000-word article, Rich wrote that he looked forward to the day when “the young will amass enough power to act” on climate change. But he neglected to ask whether they will have the knowledge to do so, in light of what is and isn’t being taught about the topic now.

The evidence to inform the answer is available, but it is not encouraging. As multiple studies have independently demonstrated, more than 97 percent of climate scientists accept that recent climate change is anthropogenic. Yet in a rigorous national survey of public middle and high school science teachers conducted in 2014–2015 by the National Center for Science Education (NCSE) and researchers at Penn State University, 10 percent of the teachers outright rejected human responsibility for global warming while teaching about it, 5 percent avoided the question of causation altogether, and more than 30 percent took no definitive stand.

Why is climate change education so uneven? In part, it is because of organized campaigns — aptly described by Rich as exhibiting “mustache-twirling depravity” — aimed at derailing, delaying or degrading attempts to improve climate education. Sometimes these efforts are top-down, as with proposals to enact state laws (e.g., in Wyoming in 2014) or to revise state science standards (e.g., in Idaho in 2016, 2017 and 2018) to downplay climate change; sometimes they are bottom-up, as with a widely publicized 2017 mailing of climate change denial propaganda to teachers.

But top-down or bottom-up, such campaigns do not tell the whole story. There are also systemic obstacles. Owing to a generations-long focus in American high schools on biology, chemistry and physics, there is no natural home in established curricula for detailed discussions of the climate system. A 2015 report from the American Geosciences Institute (which publishes EARTH) found that although 30 states required students to take a life science class to graduate from high school, only two states required students to take a class in earth or environmental sciences. So the incentive to offer such classes is absent.

Moreover, because of the historic neglect of earth and environmental sciences in K–12 education in the U.S., science teachers themselves often have not had opportunities to learn scientific content relevant to teaching climate change. In the NCSE/Penn State survey, almost 60 percent of the teachers reported never having received any formal instruction on climate change. Only 40 percent of the teachers surveyed were aware of the extent of the scientific consensus on the issue. Awareness of the scientific consensus is regarded by researchers as a “gateway” to action on climate change.

In the case of science teaching, the lack of such a gateway awareness turns out to have dismaying consequences. The NCSE/Penn State survey found a robust correlation between ignorance of the level of the scientific consensus on climate change and willingness to use pedagogical techniques that tend to foster doubt or denial about climate change, such as encouraging students to “debate the likely causes of global warming” or “come to their own conclusions” on the topic. These techniques are simply inappropriate with regard to teaching established science.

Why are science teachers willing to use such techniques when discussing climate change when they don’t use them when it comes to stratigraphy or plate tectonics? In part, it’s to avoid conflict. In the NCSE/Penn State survey, only 4.4 percent of teachers — fewer than one in 20 — reported experiencing explicit pressure not to teach the scientific consensus on climate change. But there was also evidence that teachers in counties with a lower degree of acceptance of climate change were less likely to emphasize the scientific consensus and more likely to use pedagogical techniques that foster doubt or denial.

As if these obstacles to climate change education weren’t enough, there are also broad psychological obstacles. It is hard for people to comprehend situations in which seemingly imperceptible and infinitesimal causes — such as increases in greenhouse gas concentration, measured in parts per million — turn out to have significant, even catastrophic, effects. It is also hard, especially for students in elementary and secondary schools, to come to terms with disheartening and depressing facts, such as human responsibility for recent climate change.

It’s not all bad news, though. Research is progressing on ways to teach (and otherwise communicate) climate change effectively, and to overcome the cognitive and emotional obstacles. Teachers are increasingly exposed to opportunities (e.g., from NCSE) to increase their knowledge both of climate science and of effective pedagogy for teaching it. And thanks to the combined efforts of teachers, scientists and concerned citizens in general, the forces behind organized campaigns to undermine climate change education have not found many opportunities to twirl their mustaches triumphantly.

Perhaps most encouraging of all is the fact that just as there is a scientific consensus on climate change, there is a public consensus on the importance of teaching about it, as the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication recently explained. It is vital for science teachers to know about both to have the competence and the confidence to equip today’s students — tomorrow’s citizens — to flourish in a warming world. Then, with the support of both scientists and the public, perhaps the upcoming decade will be, as Nathaniel Rich might put it, the “Decade We Start Teaching Climate Change Right.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.