by Kirsten Grorud-Colvert, Heather Mannix and Stephanie Green Thursday, December 20, 2018

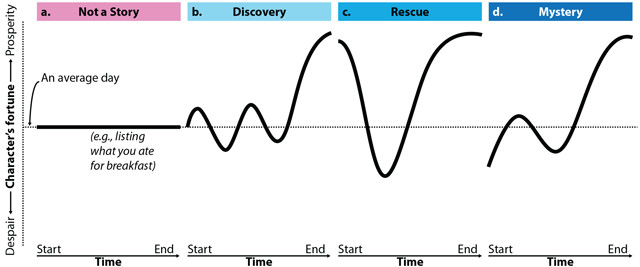

The relative shapes of selected paradigms for science stories. Solid black lines show the relationship between the main character's fortune and the progression of a story from start to finish, relative to an average day (dotted line). Credit: figure shared with permission from Canadian Science Publishing under CC BY 4.0.

Everyone has a story to tell. Scientists are no exception, especially given that scientific studies can take researchers to far-flung places around the planet, lead to amazing new discoveries about the world we live in and produce challenges that provide the drama that is so important for a great story. Stories have the power to transport listeners to the places and experiences the storyteller is sharing with them. What better way is there to show that science is relevant, exciting and conducted by people who are passionate about what they do?

Thankfully, a growing number of scientists and science communicators are recognizing the value of storytelling for sharing scientific research with audiences beyond their professional peers — something that is becoming more important every day as science helps people understand the world around us and how things are changing. However, storytelling isn’t something that comes naturally to most people, including scientists who are trained to be concise, precise and technical. These qualities are well suited for communicating with other scientists but are quite different from those involved in good storytelling. Thus, for scientists, one major challenge of storytelling is that the language of scientific publications and presentations isn’t the same language you would use to tell a story. Scientists basically need to start speaking a different language at work. Thankfully, making the key messages of a scientific study widely accessible, sharing them in ways that are meaningful to nonscientists and personalizing research in ways that make science come alive are all skills that can be learned.

Five years ago, we started thinking about how we could use storytelling to share our own work in the fields of marine ecology, science communication and science policy. We took a scientific approach to this effort — no surprise there! After diving into the research and best practices of telling stories, we put together a workshop and wrote a paper about telling good stories — speaking both the languages of science and of storytelling. As scientists who are excited about our newfound skills, we wanted to share our passion and pass on a few tips.

We were inspired by a decidedly nonscientific source, iconic American author Kurt Vonnegut, who in 1980 wrote an essay called “How to Write With Style” in the journal Transactions on Professional Communications. In it, he listed four primary objectives: Find a subject you care about; keep it simple; sound like yourself; and say what you mean. Vonnegut also put out a video offering eight tips to writing a good short story (including the gem: don’t let your reader feel like their time was wasted by reading your work), and he suggested that stories should have shapes that can be graphed.

As scientists, we already care about the subject we’re going to be writing about so that box is checked. Keeping it simple, sounding like ourselves and saying what we mean are good pointers as well — keep these in mind with every story you tell. What does he mean by a story shape, or arc, though? The shapes of different kinds of stories intrigued us from the perspective of scientists and communication specialists.

We began exploring ways that certain story types — in particular, stories involving mystery, rescue and discovery — could be useful in telling science stories. For example, research that addresses long-standing questions in science might be told as a nail-biting mystery tale, while an unexpected finding might lend itself to a story of discovery. We applied Vonnegut’s technique to map how the main characters (most often scientists in our contexts) went through ups and downs over time.

We found stories from these three paradigms often follow particular shapes, with distinctive patterns of high and low fortune for the main character (see figure on page 8). A discovery story, for example, may be shaped like a W; a rescue story like a V; and a mystery story with a rise, a fall and then a building rise. A good story needs a character that experiences both highs and lows, moving between despair and prosperity.

Of course, successful storytelling is not just about the arc. Stories also benefit from important elements like compelling characters, vivid imagery and moments of catharsis. And the key to a science story is the opportunity to include a take-home message, sharing the “So what?” of a scientific study.

The process of developing a science story: Scientists gain storytelling skills by learning and practicing techniques and developing a personal science story. Credit: figure shared with permission from Canadian Science Publishing under CC BY 4.0.

To share what we’d learned and help others develop, practice and tell compelling stories about their work, we ran a two-day storytelling workshop in association with the Society for Conservation Biology’s International Marine Conservation Congress (IMCC) in 2014 in Glasgow, Scotland.

Participants learned about key aspects of storytelling: They first identified a take-home message from their work and a personal experience that connected them to their science and their message. Then each storyteller went through the process of mapping out a story, reflecting on whether its shape matches that of a mystery, rescue or discovery tale as well as how drama and catharsis can be used to keep listeners enthralled.

We have since held the workshop at each subsequent IMCC — in 2016 in Newfoundland, Canada, and in 2018 in Kuching, Malaysia. To date, 26 ocean scientists, conservation professionals and other experts have told the stories they developed through the workshop process at live venues from an open mike on a stage. You can see some of the stories here: https://conbio.org/groups/sections/marine/stories/. The process of developing an effective science story is involved and takes time, but workshop attendees consistently report that the investment is worthwhile.

Developing storytelling skills involves more than just learning the theory and structure of good narrative, however. It also requires taking time to practice delivering stories, which our workshop participants do in pairs and groups, and creating the space to get feedback so they can reflect on and revise their story arcs and messages.

Storytelling includes a creative element, and it requires a certain level of vulnerability. As neither of these are emphasized in scientific training — scientists are typically taught to take themselves out of their work and to remain as objective as possible — it’s not surprising that this part of the learning process can be especially challenging. During the most recent workshop, we heard from our storytellers that the opportunity to share and receive feedback from their colleagues was what made the process successful. And the camaraderie that grew from talking about their passion for their work and their personal experiences helped decrease the discomfort that many scientists may have with sharing their personal stories and helped build a supportive environment. In the end, the vividness, warmth and excitement of a story is what helps a listener remember the message. At the end of every workshop, we have hosted public events at which our storytellers get up on stage with an open microphone to share their stories.

If you’re interested in learning to tell a good story, there is a wealth of helpful resources for beginners. Many examples of good storytelling can be found online and in podcasts such as StoryCorps (storycorps.org), Radiolab (radiolab.org) and Story Collider (storycollider.org). And opportunities for training are offered through science communication organizations like Intermedia Communication Training (intermediacomms.com), COMPASS (compassonline.org), the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science (aldacenter.org), Story Circles (storycirclestraining.com), Screenhouse (screenhouse.co.uk/screenhouse_story_telling_course.html) and the Beakerhead Science Communications Program (beakerhead.com/programs/scicomm).

Whatever the field, anyone who knows about science can craft a great science story and share the “So what?” of their work with practice and passion.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.