by Lucas Joel Thursday, August 6, 2015

Nova Scotia's Blue Beach preserves one of the richest concentrations of tetrapod fossils from the base of "Romer's Gap." Credit: Jason Anderson.

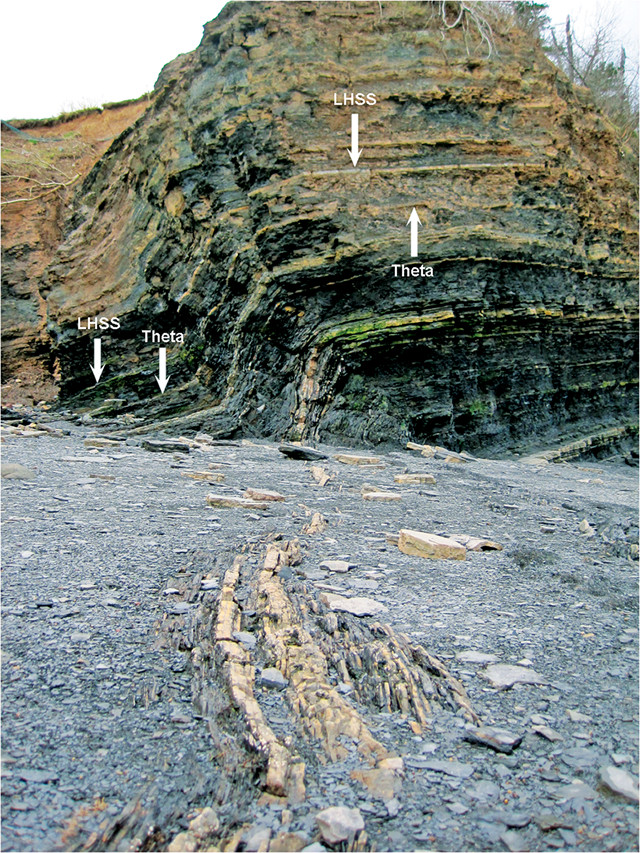

A few fossils at Blue Beach have been found in situ, especially in two horizons informally dubbed the "Theta Layer" and "Lighthouse Sandstone." Credit: Jason S. Anderson et al., PLOS ONE, 2015.

The story of how fish evolved into four-legged land animals called tetrapods has long been left incomplete by a 15-million-year gap in the fossil record, known as Romer’s Gap, which stretches from the end of the Devonian Period into the Carboniferous. Whether the gap is due to the actual absence of tetrapod fossils from this interval, or whether such fossils exist but have not been found yet has long remained unclear. A new study, however, shows tetrapod fossils from the base of the gap, adding to a growing list of discoveries that appear to be closing the gap.

“Romer’s Gap,” named after the famous paleontologist Alfred Sherwood Romer, who first noted it, extends from about 360 million to 345 million years ago. Fish-like tetrapod fossils dating to before the gap exhibit primitive arms, legs, fingers and toes. Specimens from within the gap, though, have been difficult to find, frustrating researchers who have long suspected that tetrapods further developed basic adaptations for life on land during this time.

In the new study published in PLOS ONE, researchers led by Jason Anderson, a paleontologist at the University of Calgary in Canada, detail a group of fossils collected at Blue Beach, near Hantsport, Nova Scotia. “This is one of the first tetrapod fossil assemblages described from the base of Romer’s Gap,” Anderson says. “We don’t name any new species here, but what the study helps show is that, instead of being just one giant question mark, the gap actually contains a diverse group of tetrapods, some of which are similar to pre-gap tetrapod species.” Researchers dated the rock layers at Blue Beach using fossilized pollen; the pollen record is relatively complete, so it is used to date and correlate fossil localities around the world.

Previous studies suggested that low atmospheric oxygen levels may have prevented early tetrapods from taking the evolutionary steps necessary to become full-time land-dwellers during Romer’s Gap because there was not enough breathable air. But this idea has been questioned in light of fossil discoveries like those at Blue Beach, as well as discoveries from Scotland beginning in the 1990s. “Oxygen levels may have varied, but they likely did not have an impact on tetrapod evolution,” Anderson says. “At Blue Beach, we have footprints, which tell us that tetrapods were in fact on land and were not kept in the ocean due to a lack of air.”

Paleontologists have known about the fossils at Blue Beach since the 1950s, but their significance has only recently come to light. This is partly due to the fact that collecting fossils at Blue Beach is difficult, as the area sees some of the largest tides in the world. Aided by locals who walk the beach and bring fossils they find to a local museum, the tetrapod story recorded at Blue Beach has slowly been coming together.

“One of the most interesting things about this new assemblage of fossils is that it contains tetrapods similar to Devonian forms such as Acanthostega, alongside others that are reminiscent of known Early Carboniferous forms,” says Per Ahlberg, a paleontologist at Uppsala University in Sweden who was not involved in the new research. “This suggests that the Devonian and Carboniferous tetrapod faunas grade fairly smoothly into each other, contradicting previous notions that many tetrapod species went extinct at the end of the Devonian.”

Anderson and Ahlberg both say they think Romer’s Gap will soon be a thing of the past. “We show pretty convincingly that the gap is simply a failure of collection — it is an artificial bias,” Anderson says.

Anderson says the next step is to continue working on additional Blue Beach fossils that have been collected but not yet described. “There’s still a lot of work to be done; there are literally tons of fossil-bearing rocks that have yet to be prepared.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.