by Lucas Joel Tuesday, May 22, 2018

Capetonians fill bottles and buckets at natural springs near the city. Residents use the spring water to supplement their rations. Credit: Lucas Joel

The city of Cape Town, South Africa, is bone dry. In 2017, after two straight years of drought, a third drought year offered more of the same. This past January, city leaders announced that they would shut off the taps to the municipal water supply in April because that was when “Day Zero” — the day when the water supply would run dry — was predicted to occur. Day Zero has since been pushed back to sometime in 2019, but, for 4 million Capetonians, living under the specter of a day without water is the new normal, and signs of that reality litter the city. Sometimes literally.

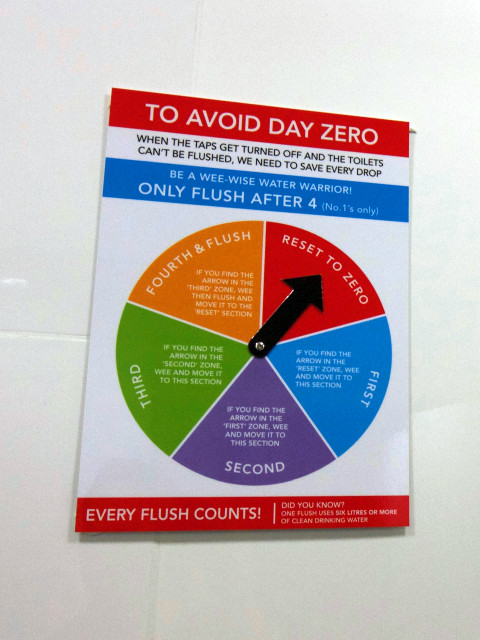

Above a toilet in the bathroom at the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Future Water Institute (FWI), I found a sign that looked like a board game. “TO AVOID DAY ZERO,” the sign announced in all capital letters. “BE A WEE-WISE WATER WARRIOR! ONLY FLUSH AFTER 4 (No. 1’s only).” In the middle of a pie chart was a plastic arrow that restroom visitors are meant to advance through numbered slices marked one through four — to track the appropriate number of uses..

“It’s raised a lot of issues with our cleaning staff,” says Jessica Fell, a hydrologist at the FWI. “We’ve given them chemicals that they can spray into the toilet bowl, which completely neutralize the smell.”

Signs like this one at Cape Town University ask residents to conserve water in public bathrooms to stave off Day Zero. Each new user moves the arrow forward one position, until the fourth user flushes. Credit: Lucas Joel

Such careful use of water is now a part of everyday life in Cape Town. To force water savings, the city decreed earlier this year that each person can use only 50 liters of water per day. Compare that to per capita U.S. average of 300 to 380 liters per day for domestic use, and the extent of the city’s rationing comes into focus.

To adapt to the mandate, denizens of Cape Town flock to natural springs that flow from the sandstone mountains that surround the city, like Table Mountain. At the springs, people queue for water with plastic jugs and buckets in tow. During my visit in March, someone pushing a dolly loaded with full 5-gallon buckets hit a bump in the road, and their buckets toppled, spilling their precious water onto the pavement.

Meanwhile, water conservation efforts are on the rise as well. Restaurants serve drinks in paper cups to avoid using water to wash dishes, while individuals and families are learning to recycle the “gray” water they use in their sinks and showers. In one household I visited in Rondebosch, near UCT, the residents collected their shower water in a bucket and used it to flush the toilet. At another dwelling, a resident described how they limit their showers to just 90 seconds, and they wear their clothes multiple times before washing them.

While most of southern Africa receives its rain from the South Africa Monsoon between December and February, coastal Cape Town instead usually receives the bulk of its precipitation from seasonal rains that fall between June and August, which have now been below-average for three consecutive years. The science behind what is driving the change in weather patterns, however, is not clear.

Piotr Wolski, a hydroclimatologist at UCT, says that “there is some role of climate change,” but that the region is also historically drought-prone, so natural climate variability is likely playing a big role.

Currently, the city’s reservoirs stand mostly empty. At the time of this story, the reservoirs that feed the city and surrounding areas were cumulatively only at about 21.4 percent capacity. And if the coming winter is not a wet one, the reservoirs — which depend entirely on mountain runoff — will turn into even bigger dust bowls.

If the reservoirs are so depleted, why has the city delayed Day Zero repeatedly? Fell explains that it was partly to calm the city’s crisis-fatigued populace, and also because it does not look like the reservoirs will fall to critical levels (dams average 13.5% storage) within the next few months.

Wolski says there is no telling whether this winter, which is just beginning, will be wet or dry. Whatever happens, the city has plans to exploit groundwater reserves that have so far gone untapped. This is a smart move, Fell explains, because another proposed strategy — building desalination plants to purify ocean water — would be extremely costly. Although one hospital has begun construction of a desalination plant. Until the groundwater becomes available, however, people will keep their eyes on the sky this winter, and hope for rain.

“We’re very much hoping for rain” this winter, Fell says. “We don’t want to think about a scenario where there’s not.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.