by Terri Cook Tuesday, December 30, 2014

These hydroelectric turbines at Oroville Lake in California should be well below water; however, due to the ongoing severe drought, they have been exposed. Credit: ©Shutterstock.com/David Brimm.

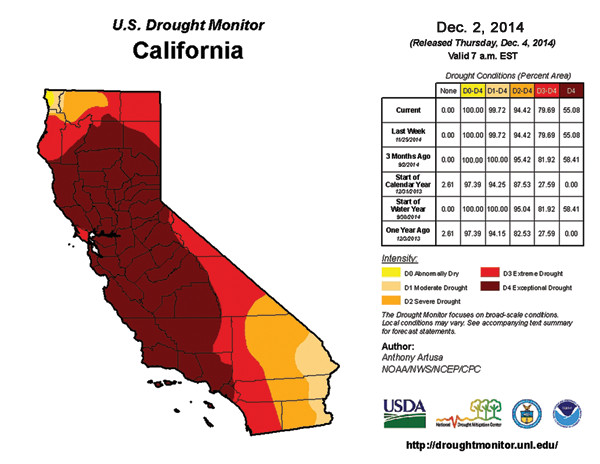

With 100 percent of California experiencing moderate to exceptional drought conditions last year, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, Gov. Jerry Brown mandated the tracking of monthly personal water usage for the first time. In addition, water districts around the state also took up varying degrees of drought restrictions, including such strategies as raising water prices and severely limiting outdoor irrigation. But whether these restrictions will make a dent in California’s water shortage amid the ongoing and historic drought remains to be seen.

The new monthly reporting requirement, called the residential gallons per capita per day (GPCD), was ordered into effect for one year by the State Water Board last July. GPCD estimates the daily water use by residential customers for almost 400 urban water agencies, representing 35.5 million Californians, more than 90 percent of the state’s population.

The order also prohibits all urban California water users from applying potable water to driveways or sidewalks; allowing runoff when irrigating with potable water; using a hose without a shut-off nozzle to wash a car; or using potable water in a fountain or other decorative water feature that doesn’t recirculate the water. It also requires urban water suppliers to impose restrictions on outdoor irrigation.

Although these requirements form the basis for the water restrictions enacted by most of the state’s urban water suppliers, each urban district’s specific restrictions vary widely, resulting in a profusion of drought regulations that have proven difficult for local consumers to follow. To make it easier for consumers, the Association of California Water Agencies mapped the various regulations by district at www.acwa.com/content/drought-map.

In addition, each urban water supplier has variously defined stages that increase restrictions as the drought progresses. Stage 1 is usually an alert that notifies the public that a potential water shortage may occur if water demands remain high or dry weather continues. Stage 2 typically enacts mandatory restrictions on outdoor irrigation and often includes increased water prices; Stage 3 is usually triggered by an extreme water shortage and typically includes more aggressive mandatory restrictions and even higher water prices.

As of Dec. 2, 2014, about 94 percent of the state of California was under severe to exceptional drought conditions. Credit: U.S. Drought Monitor.

Given this patchwork approach, it’s not surprising that the conservation results have so far also varied considerably, both within and among regions, according to year-on-year data for September released by the State Water Board in early November.

Because water use varies widely between the cooler, wetter north of the state and the warmer, drier south, the GPCD data can’t be compared directly from region to region. In Northern California, for example, the city of Redding, which provides water to about 90,000 customers, cut its GPCD from 255.4 in September 2013 to 208.2 in September 2014, an 18.5 percent decrease. The city has enacted Stage 2 mandatory restrictions, which prohibit exterior watering during the heat of the day and limit it to a maximum of three days per week.

Yet the data show that implementing mandatory drought restrictions is no guarantee of success. The city of Susanville, 180 kilometers east of Redding, has also implemented Stage 2 restrictions, but during the same period, the usage for the population of 9,300 actually increased from 136.2 to 287.6 GPCD, or 111 percent.

In Central California, the 847,000 people served by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) averaged 45.7 GPCD, a 9 percent savings compared to the previous September. The SFPUC has invoked Stage 1, requiring its customers to reduce potable water use for outdoor irrigation by 10 percent. Less than 120 kilometers south, the city of Santa Cruz declared a Stage 3 Water Shortage Emergency and in May instituted a water allotment of 249 gallons per family of four, per day, charging its 95,000 customers higher rates for water consumed beyond that level. Its usage dropped 29.2 percent, from 63.4 to 44.9 GPCD, one of the biggest decreases and lowest usage rates in the state.

Less than half an hour east of Santa Cruz, the city of Watsonville has enacted only voluntary measures, asking for the same 20 percent reduction requested by Gov. Brown in a January 2014 State of Emergency declaration. The 66,000 water customers served by the city have reduced their usage by 14.3 percent, from 113.1 to 96.9 GPCD — a larger drop than many municipalities have achieved with mandatory Stage 2 restrictions.

In Southern California, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP), which serves 3.9 million people, and the city of San Diego, which provides water to 1.3 million customers, have both invoked Stage 2 mandatory restrictions. The LADWP has observed an 8.3 percent drop in water use, from 101.2 to 92.8 GPCD, whereas San Diego’s usage, which was lower to begin with, has dropped 3.2 percent, from 84.5 to 81.8 GPCD.

Heavy December rainfall and floods throughout parts of the state did little to relieve the drought and as of late December, most of the same restrictions were still in place.

[Editor’s Note: This article was updated on Jan. 28, 2015, to correct the amount of Santa Cruz’s water restriction. It was 249 gallons per family of four per day, not 249 gallons per person per day.]

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.