by Logan Nagel Tuesday, May 10, 2016

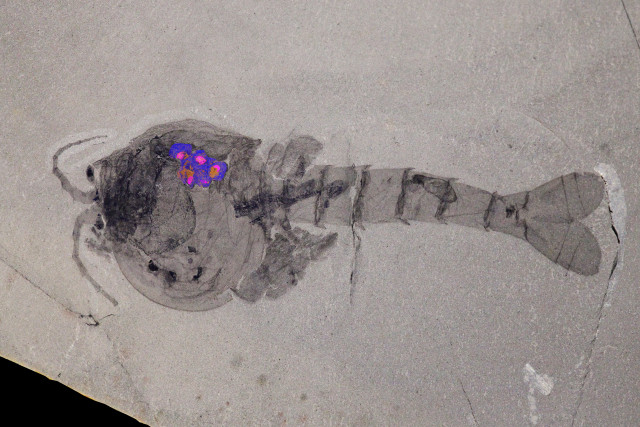

A specimen of the Middle Cambrian arthropod, Waptia fieldensis, found with a cluster of eggs (highlighted) under its carapace in the Burgess Shale. Credit: ©Royal Ontario Museum

Parenting behaviors of many modern animals are well known. Marsupials, like kangaroos, keep their young in pouches, and brown bear mothers are famously protective of their offspring, for example. By caring for their young, parents can increase the survival chances of their offspring. But for all we know about animals today, the origins of parenting are much less understood. Now, a new study has shed light on one of the earliest demonstrated examples of parental behavior in animals: brood care among ancient shrimplike arthropods.

In the new study, published in Current Biology, Jean-Bernard Caron of the Royal Ontario Museum and Jean Vannier of the Laboratory of Geology in Lyon, France, investigated a newly-discovered cache of fossilized _Waptia fieldensis, _marine arthropods that grew to about 10 centimeters long and lived about 508 million years ago in the Middle Cambrian. Although W. fieldensis has been recognized by paleontologists for a century, the details of its life cycle and, in particular, its reproductive habits are poorly understood. However, the remarkable condition of this new discovery in southwestern Canada’s fossil-rich Burgess Shale has offered scientists a valuable chance to gain insight about both this ancient animal’s life and parenting tactics.

In the Burgess Shale, Caron and Vannier identified 1,845 specimens of W. fieldensis, five of which had clusters of roughly two dozen 2-millimeter-long ovoid objects in a void under their abdominal carapace. The consistency in size, placement and composition of the objects suggested they were fossilized embryo-containing eggs, which the researchers studied in detail using digital imaging, polarizing light and scanning electron microscopy. By measuring elemental concentrations in clearly-defined areas of the fossil eggs, the researchers identified different parts of the eggs, from the aluminum- and potassium-rich outer membranes to the carbon-rich yolks and embryos.

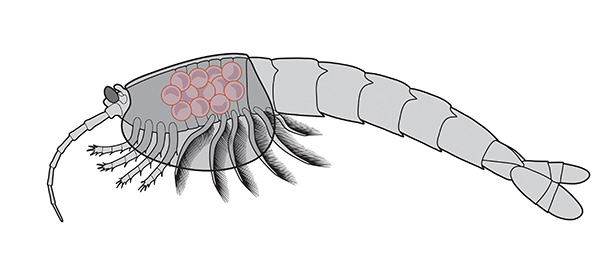

This reconstruction shows how W. fieldensis would've looked in life with eggs brooded between its carapace and body. Credit: Danielle Dufault, ©Royal Ontario Museum

The researchers noted that the anatomy and elemental abundances in the ancient eggs resembled those in modern crustaceans, such as lobsters; a female lobster lays eggs and then provides brood care by anchoring them to the underside of her tail until hatching. For _Waptia, _Caron and Vannier wrote that their findings indicate an “extended investment in offspring survivorship.”

The new find is significant for the paleontological community, in part because the eggs are the oldest ever found with preserved embryos by about 50 million years. A 2014 study documented broods of embryo-carrying eggs in 450-million-year-old ostracods; while a separate 2014 study identified 515-million-year-old brooded eggs without embryos in other arthropod specimens. The new specimens are also important because of the degree of soft-tissue preservation, notes David Siveter, a paleontologist at the University of Leicester in England and lead author of the ostracod paper. Previous research on ancient arthropods has focused mostly on shell development, he says, while examples of soft-tissue preservation have been very rare. But “the fossil record is wonderful and continues to surprise us. … The fact that we have eggs [that are] 500-million-year-old is astounding,” he says.

The small number of fossils found with preserved eggs might seem like an obstacle to clear conclusions about the arthropod’s parenting behavior, but Caron says that the small sample size — just five egg-bearing specimens out of 1,845 total — might simply be an indication that _W. fieldensis _may only have spawned rarely.

Overall, the new results offer a much clearer view on an ancient arthropod that has long been enigmatic_, _Caron says. Future work, he adds, will likely focus on morphological differences between the sexes in the animal, because, currently, males and females can only be differentiated by the presence of eggs.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.