by Abby Seadler Friday, March 23, 2012

Many low-lying coastal communities in Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, Washington and Puerto Rico have tsunami warning signs and evacuation plans in place. NOAA

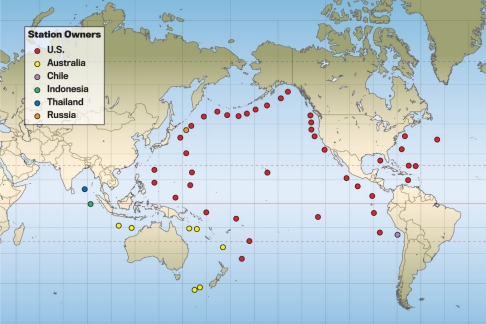

DART buoy locations around the world. DART buoys help track tsunamis in real time. NOAA National Data Buoy Center

Abby Seadler is the member society services manager for the American Geosciences Institute and writes about about the government and policy developments for EARTH. Abby Seadler

“It is not a question of whether it will happen, but when it will happen,” said John Schelling, addressing the room at a Congressional Hazards Caucus briefing last week. The briefing, entitled Tsunami Preparedness: Understanding our Nation’s Risk and Response, brought together Schelling, who is the Earthquake and Tsunami Program Director for the Washington State Emergency Management Division, Eddie Bernard, scientist emeritus at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, and John Orcutt, a geophysicist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography to put forward one question: Is the U.S. tsunami-ready?

At least five measurable tsunamis occur each year, and in the past decade two have resulted in devastation. With no warning systems in place, the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami left more than 200,000 people dead, and crippled the region with damage totaling more than $13 billion. Yet the real surprise came in March 2011 when the world watched in horror as the tsunami caused by the magnitude-9.0 Tohoku earthquake swallowed portions of the most tsunami-ready country on the planet. The rest of the world took note: If Japan is vulnerable, so are we.

The United States is at risk not only from distant tsunamis — the kind that originate across the ocean and propagate toward us, like the one that came from Japan and caused damage in Hawaii, California and Oregon — but also from local tsunamis that are triggered by earthquakes or landslides directly off our own coasts. And although the risk of enduring a tsunami remains the same, our vulnerability is constantly increasing as more and more people choose to live and vacation on or near the coast.

The Tsunami Warning and Education Act (Public Law 109-424) is the solitary piece of legislation charged with ensuring that, when the time comes, the United States is tsunami-ready. Passed in 2006 in the wake of the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, the act is an extension of the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program (NTHMP) — a joint effort by federal and state governments to protect U.S. coastlines from tsunami hazards. The act has four provisions: mitigation, warning, research and international cooperation.

In the case of local tsunamis, when residents only have a few minutes to get to safety, community mitigation and warning systems have the most impact. For example, in Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, Washington and Puerto Rico, the act has helped create tsunami-ready communities, armed with tsunami hazard signs, evacuation routes, outdoor warning systems and hazard maps. However, although many of these systems are in place, they are not standardized, which could lead to potential confusion and makes sharing data and information more difficult.

On an international level, the Tsunami Warning and Education Act has helped promote the widespread use of DART (Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis) buoys. Placed strategically throughout the oceans, these buoys provide a tsunami monitoring system that records and disseminates critical information to help create tsunami flooding models in real-time. Prior to 2004, only three of these buoys were in place off the west coast of the United States, but today there are more than 50 buoys in throughout the world’s oceans owned by seven different countries that all collect and share data.

A bill was proposed by Rep. Pedro Pierluisi, D-Puerto Rico, to amend the 2006 act to include funds for establishing a Caribbean tsunami warning center in Puerto Rico. Pierluisi’s new bill, the Tsunami Forecasting and Warning Improvement Act of 2011 (H.R. 1100), is making its way through the House of Representatives, and was recently referred to the Subcommittee on Technology and Innovation.

Experts suggest other revisions as well. First, Bernard told participants at the briefing last week that technical standards for hazard maps, preparedness, education and mitigation should be put in place to allow for a unified understanding of tsunami safety procedures. And the act should include a provision for an oversight committee to maintain these standards. Second, Bernard said, the tsunami warning system should transition to graphical flooding information in order to develop products and procedures for ports and harbors. Finally, he noted, the U.S. should increase international cooperation and dissemination of our technology because it is in our best interest for other countries to implement these standards as well.

In honor of National Tsunami Preparedness Week (March 25–31), I hope you all will take note and visit www.tsunami.gov to help yourself and others become more tsunami-ready, especially if you live in a coastal area.

But, if you take nothing else away, make sure to take note of these four things when you visit a coastal area: First, be aware of the natural warning signs. For a local tsunami, that is if the ground shakes for a prolonged period of time; and for a distant tsunami, note if there are sudden changes in tide or the ocean starts to make a roaring sound. Second, know what areas are at risk. Third, know where to escape. And finally, practice evacuations. After all, you never know when an earthquake in Japan might interrupt your Hawaiian vacation.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.