by Meg Marquardt Thursday, January 5, 2012

Artistic view of _Leviathan melvillei_ attacking a baleen whale. C. Letenneur (MNHN)

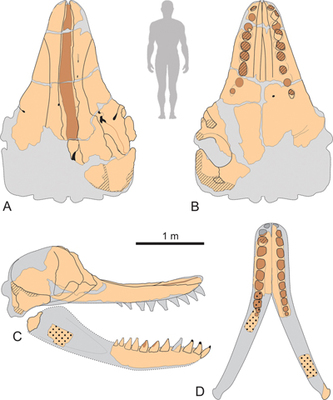

Schematic drawings of the skull and jaw of _Leviathan melvillei_. G. Bianucci (Universita di Pisa)

It reads like a passage from a horror story: a monster 15 meters long with gigantic, gnashing teeth capable of tearing apart other whales. But it’s not fiction. Researchers recently discovered the fossils of an extinct sperm whale with teeth bigger than a human head.

It has, however, been given a storybook name. The new species is known as Leviathan melvillei, a name borrowed from Herman Melville, author of Moby Dick.

Klaas Post, honorary curator of fossil mammals at the Natural History Museum Rotterdam in the Netherlands, and his colleagues were traveling through a stretch of desert about 50 kilometers southwest of Ica, Peru, in 2008 when they spotted what at first looked like elephant tusks. But they turned out to be teeth from an even less-likely animal: a giant sperm whale.

Perhaps the discovery shouldn’t be a complete surprise. Fossils of the great shark, Carcharocles megalodon, have been found in the same region. Both animals would have lived about 12 million to 13 million years ago during the Miocene. And like megalodon (at 20 meters long, thought to be one of the biggest fish to have ever roamed the sea), L. melvillei is breaking a few records of its own. With jaws more than 5 meters wide, it had the biggest bite of any mammal to have ever lived.

But L. melvillei was quite different from modern sperm whales (hence scientists gave it a new genus name). Today, sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) have fairly small lower teeth and almost no teeth on the upper jaw. They primarily eat squid, which they pull in via suction. But L. melvillei had teeth as large as 12 centimeters wide and 36 centimeters long on both its upper and lower jaw, which would have afforded it a much different tactic for hunting: According to the paper published today in Nature, the researchers suspect that the aggressive whale grabbed prey with its teeth, living off of smaller baleen whales (whales with comb-like dental plates instead of teeth, such as the humpback).

L. melvillei’s discoverers believe that a changing climate and a drop in the diversity of and an increase in the size of prey toward the end of the Miocene led to the downfall of the great whale.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.