by Brian Fisher Johnson Thursday, January 5, 2012

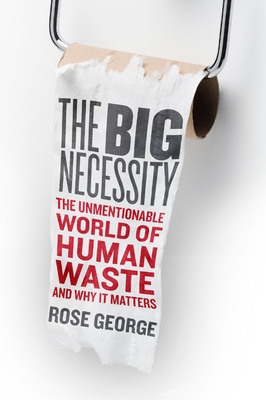

'The Big Necessity,' a new book by freelance journalist Rose George, was released on Oct. 14. Courtesy of Metropolitan Books

Displays like this from the German Toilet Organization attempt to raise awareness about the importance of human waste management. Courtesy of the German Toilet Organization

In her new book, "The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste and Why It Matters," freelance journalist Rose George argues that experts and citizens alike must overcome their aversion to all things fecal — or else face one of the most serious public health risks on the planet. If handled properly, George says, waste water can even be reclaimed as potable water. Recently, EARTH contributor Brian Fisher Johnson talked with George about her book, which was released on Oct. 14.

BFJ: At the start of your book you talk about your realization that for many people in this world a place to go to the bathroom is a privilege, not a right. What do you mean?

RG: There’s a rather stunning statistic that four in 10 people in the world have absolutely nothing to serve as a toilet. So what they generally do is something called open defecation, which means they use whatever they can, which is generally the nearest roadside or bush. This is environmentally not a very good idea because human feces can carry so many bacteria, viruses and worms.

BFJ: It seems a lot of people would be disgusted by the idea that you can turn waste water into clean water. After writing the book, what do you find to be the most effective approach to helping fecal-phobic populations deal frankly and comfortably with sanitation?

RG: It’s very difficult. In the States there’s a very interesting thing happening with the issue of whether waste water can and should be turned into drinking water. For example, in many districts in the States, cleaned effluent is discharged into water that becomes the drinking water supply.

Ideally the effluent is cleaned, but there are situations where the system breaks down. In Milwaukee in 1994 there was a huge outbreak of Cryptostoridium, a small organism which is very hard to treat because it is resistant to chlorine. Up to a hundred people died.

There’s a very expensive re-use system in Orange County, California which has opened amid enormous controversy. It uses all of the state-of-the-art equipment like reverse osmosis and UV filters to clean the waste water, but there is still a scandal. I don’t know if the answer is to educate people — to tell them how the system works already — or to educate them on how the treatment process works and how clean it can be.

BFJ: The U.S. can obviously afford the best water treatment system money can buy. What country in your opinion does the best job it can with what little resources it has?

RG: One impressive place is China. China has always been quite at home with excrement and has used human feces to fertilize its fields for about four thousand years. Now they have a very interesting program of building biogas digesters in rural households. A biogas digester is an underground sealed tank. You simply hook up your latrine and ideally your pigsty — because the digester needs a good volume of excreta — so that human and animal excreta drains into the tank. You let it digest, and then tap off the methane, and it can be used for cooking or lighting or even powering showers. It’s very efficient. The slurry that comes out the end is much safer than the raw excrement that has been used for fertilizer up until now. They have about 16 million installed so far. And it’s not just in China. In the city of Lille in northern France they’ve got ten buses running on methane from their sewage works. And they claim that it’s carbon neutral with much fewer particles coming out of the exhaust.

BFJ: Besides global warming, would you say that sanitation is the biggest environmental challenge we face right now?

RG: If you look at the health statistics it certainly is. Excrement all over the place pollutes the environment but it also pollutes people. That’s why diarrhea kills more children than tuberculosis, malaria or HIV/AIDS combined. It’s the biggest killer of children under the age of five in the world. Environmentally, the big problem is that sewage going into the water needs to be treated. That doesn’t just go for poor countries like India, Thailand or Burma. Until 2004, the city of Barcelona didn’t have a sewage treatment plant. Until 2003, Brussels didn’t have one. We’re still polluting our seas. If polluting our seas goes untreated, then that’s a pretty pressing global environmental challenge.

BFJ: After writing a book like this, your comfort level with excrement must be higher.

RG: I started out like everyone else, in that I didn’t really think about it. But the three years I’ve spent researching this book have been great fun. I’m not happy tramping through excrement any more than anyone else. Having said that, I absolutely admire pragmatism in this area and I think it’s essential that we not be hampered by prudishness anymore.

It’s become a taboo because we don’t have any neutral words for it — because all of the words we use for it have been turned into swear words. Steven Pinker writes about this very interestingly. When human waste was much more central to our life — we were basically stepping in it every time we walked in the streets — our swear words were religious. “Damn” was very powerful. But now they all have to do with human feces. That’s only happened in the two hundred years since the flush toilet became popular. I think it’s time to at least take a look at that and question whether we need to be so scared of our own natural processes.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.