by Rachel Crowell Friday, August 3, 2018

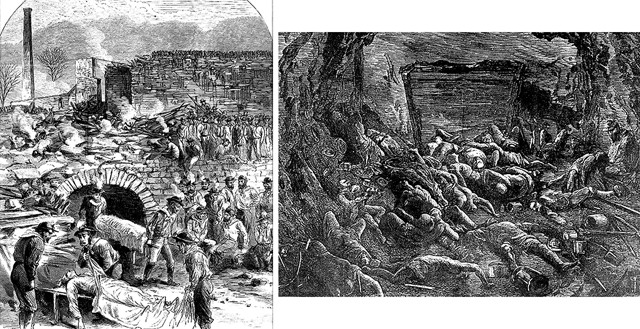

Harper's Weekly illustrations of the Sept. 6, 1869, fire at the Avondale Colliery that killed 110, including five children and two rescuers. When the coal breaker caught fire and blocked the only exit, the miners attempted to seal themselves off, but were asphyxiated. Credit: both: public domain.

In the mid-19th century, American industry was fueled by coal, which was provided largely by the anthracite coal mines of eastern Pennsylvania. The work drew tens of thousands of immigrants, including experienced English and Welsh miners, and many fleeing the Irish Potato Famine. But the work was dangerous, and each year thousands of workers died in the mines and many thousands more were seriously injured. In one of the worst disasters of this era, a fire at the Avondale Colliery in Plymouth, Pa., trapped and killed 108 miners, including five boys, as well as two men who attempted to rescue the workers.

While it was neither the first nor the last mining fire of its time, Avondale had a significant effect on the history of labor unions and mining safety regulations. One year later, Pennsylvania created the first mining inspection law for anthracite (hard coal) mines. Eight years after that, the law was extended to include bituminous (soft coal) mines, setting a precedent that other states soon followed.

Additionally, after the disaster, thousands of miners flocked to join the Workingmen’s Benevolent Association (WBA), the first industrywide labor union for anthracite miners, according to an article published in the journal Labor History. Increased unionization drew attention to the Molly Maguires, an alleged secret Irish society that advocated for workers’ rights, sometimes resorting to violence.

Some of the details of this transformative disaster are muddled by the nearly century and a half that has elapsed since it occurred, and because of “how far some of the numerous historical references to the Avondale disaster have strayed from the truth,” according to a historical report about the fire. For example, reports in 1916 and 1946 by the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Mines erroneously tallied 179 deaths from the fire. Yet certain details from the tragedy are undisputed and were key in the eventual adoption of mine safety protections.

Pennsylvania’s first mine safety law was passed by the state legislature in April 1869, but that law, created just months prior to the mine fire in Plymouth, didn’t prevent the conditions that contributed to the fire’s deadliness, notes the website Explore PA History.

The 1869 law was partly a result of lobbying efforts organized by the WBA’s Committee on Political Action, according to a Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) account of the history of Irish workers in American mining. John Siney, the Irish immigrant founder of the WBA, became a miner after immigrating in 1863 to St. Clair, Pa., in Schuylkill County. There, he helped lead a six-week-long strike in 1868 that succeeded in preventing miners’ wages from being slashed for the second time in half a decade. He also led strikes to enforce state-legislated eight-hour work days.

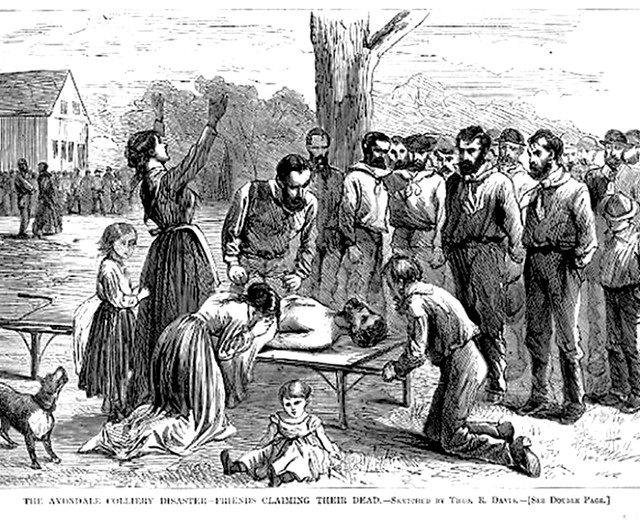

Harper's Weekly illustration of the aftermath of the Avondale Colliery disaster, which devastated the population of the small town of Plymouth, Pa. Credit: public domain.

The narrowly drafted 1869 law called “for the better regulation and ventilation of mines and for the protection of the miners” — but only in Schuylkill County. It outlined many requirements, including that mines possess ventilation in the form of furnaces or suction fans, that each mine employ a boss who would perform a safety inspection each morning before workers entered, and that systems be installed to enable communication between the mine and the surface. Under penalty of fine, it also prohibited mines from having workers ride to the surface in loaded cars and stipulated that the law would be enforced by newly designated inspectors authorized to enter and inspect the mines and machinery at “reasonable” times.

However, the law did not apply in neighboring Luzerne County, where the Avondale Colliery was located, and none of the new regulations accounted for that mine’s deadliest shortcoming: It was equipped with just one exit.

Catastrophe engulfed the Avondale Colliery at approximately 10 a.m. on Sept. 6, 1869 — the miners’ first day back at work following a seven-day strike. The fire took hold in the coal breaker, which proved perilous. At Avondale, the breaker — where coal was sorted from rock and broken into various sizes — was built directly above the shaft that served as the sole opening to the mine. England had, by this time, banned mines from installing coal breakers above shafts, but the practice was still being implemented in the northeastern U.S. According to Explore PA History, it was the practice of the company that ran the Avondale mine — as well as other coal mining companies — to keep small fires “burning at the bottom of shafts to create drafts that promoted better air circulation for the working miners.”

According to the historical report on the fire, Alexander Weir, an engineer at the Avondale mine who was working aboveground that day, was the first to notice the flames shooting up the mine shaft. Sparks from the ventilating furnace had ignited the wooden breaker. The flames rushed “up the shaft with great fury and with a sound not unlike an explosion,” leaving Weir with just enough time to blow his whistle, alerting workers more than 60 meters below to “arrange matters to prevent a boiler explosion.” As the rapidly progressing blaze turned the shaft into “a roaring inferno which no man could approach,” Weir jumped out of the way. The burning breaker consumed the oxygen from the mine below and flooded it with carbon monoxide.

Soon, the area around the mine was engulfed by a line of fire that extended more than 90 meters from the mine’s head house, the structure enclosing the mine entrance, to the nearby railroad tracks. The historical report describes “a plane of fire” running toward the hill above, then shooting up “in one immense column into the air, while dense clouds of smoke envelop[ed] all surrounding objects.”

As word of the fire spread, the families of the trapped miners rushed to the mine. A bucket brigade was organized to transport water from a tanker until fire engines arrived, first from neighboring Kingston and then from Scranton. By the middle of the afternoon — several hours after the blaze was first noticed — streams of water from the two engines had “subdued the fire in a great measure,” according to the report. But it would still be some time before the blaze and deadly fumes were controlled enough that the mine could be safely entered.

With the fire extinguished from above, men at the surface cleared debris — largely the remains of the breaker, which had collapsed into the shaft amid the fire — from the mouth of the shaft and installed a hoisting device powered by horses that could be used to descend into the mine. To ascertain the safety of the area below, they sent down a small dog and a lighted lantern. At 6 p.m., the canine and the lantern were hoisted back up. The dog survived but the lantern’s flame was snuffed out.

Confusion ensued. After calling down the shaft into the mine, some thought they heard miners below answer that they were alright. “Immediately, cheer after cheer went up from the assembled multitude, but the most experienced miners were not of the same mind. They could hear no answer,” the report notes.

Charles Vartue, 85, volunteered to descend into the mine’s shaft to investigate. He emerged unscathed but reported that more than one man would be needed to dig through the debris in the shaft to get into the mine. Next, two men — Charles Jones and Stephen Evans — went down together, discovering two dead mules and a closed door. After pounding on it and receiving no answer, they ascended.

Next, Thomas W. Williams and David Jones volunteered to enter the mine but died from lack of oxygen. “It took two days of clearing debris and poisonous gases from the mine before rescuers reached the first victims,” who had been asphyxiated and discovered in various states. “Some men had fallen while running, another was kneeling, and a father was found with his arm around his son,” Explore PA History notes.

In the wake of the Avondale Colliery catastrophe, Siney implored miners: “You can do nothing to win these dead back to life, but you can help me to win fair treatment and justice for living men who risk life and health in their daily toil,” he said. The General Council of the WBA sent a committee of miners — formed by representatives from each county union — to the capital. Their lobbying resulted in the Mine Safety Act of 1870, which stipulated, among other things, that each mine had to have more than one exit.

Despite this modicum of progress, the mining industry remained rife with dangers and abuses, which the Molly Maguires worked to settle on their own terms. The group, which led riots in Ireland in the 1840s against exploitive English landowners, was purportedly brought to the U.S. by Irish coal miners who had immigrated to Pennsylvania.

Disputes between coal operators and their employees stemmed from many issues. Besides the dangerous working conditions, there were also child labor issues — with boys as young as 6 employed as “breaker boys” — as well as overcrowded and unsanitary company housing, exploitive company stores, and little or no money offered to the families of workers who were injured or killed on the job.

The Molly Maguires were accused of delivering “coffin notices” threatening to kill mining supervisors and strikebreakers. However, it is unknown whether they murdered anyone, or indeed if any such secret society existed in the U.S. In the 1860s and ‘70s, Schuylkill County recorded a dozen or more murders per year. In the 1870s, 24 victims were English and Welsh mine bosses. The arrest, conviction and hanging of alleged Molly Maguires for some of the murders was based on the questionable testimony of James McParland, a Pinkerton agent who infiltrated the group at the behest of Franklin B. Gowen, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad.

Gowen, who was known for starving striking workers into submission and other ruthless behavior, was attempting to break the WBA and establish a monopoly on the Pennsylvania anthracite mines. He was also a former district attorney for Schuylkill County, who then served as the special prosecutor in the trials of the 20 accused Molly Maguires, none of whom were permitted to testify on their own behalf and all of whom were found guilty.

On June 21, 1877, 10 of the convicted men were executed by hanging. On Dec. 18, 1878, the alleged leader, John “Jack” Kehoe, a local tavern owner and labor activist who had stymied Gowen’s political career, was executed for the murder of F.W. Langdon, a mine boss who had died 15 years earlier, three days after being involved in a bar fight. Langdon had never mentioned Kehoe as one of his attackers.

In 1979, the governor of Pennsylvania, Milton J. Shapp, posthumously pardoned Kehoe, officially recognizing Gowen’s subversion of the criminal justice system. “The Molly Maguire trials were a surrender of state sovereignty. A private corporation initiated the investigation through a private detective agency. A private police force arrested the alleged defenders, and private attorneys for the coal companies prosecuted them. The state provided only the courtroom and the gallows,” wrote Carbon County Judge John P. Lavelle in his 1994 book, “The Hard Coal Docket.”

The first federal mine safety statute wasn’t passed by Congress until 1891, 22 years after the Avondale Colliery fire. It only applied to coal mines. (Noncoal mines weren’t regulated by such statutes until the passage of the Federal Metal and Nonmetallic Mine Safety Act of 1966.) The Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act — a more comprehensive law that covered both surface and underground mines, required inspections, increased enforcement power, set penalties for safety violations (including criminal penalties for willful violations), established health and safety standards, and provided compensation to miners who contracted black lung disease — was passed in 1969, a century after Avondale.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.