by Timothy Oleson Tuesday, August 23, 2016

The towns of Jubail and Dammam on Saudi Arabia's Persian Gulf coast played major roles in the early history of oil exploration in the country. Credit: ©NormanEinstein, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported.

Saudi Arabia currently produces about 11 million barrels of oil per day, edging out Russia and the U.S. to rank first in the world in production, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The desert kingdom also has proven reserves of more than 260 billion barrels — spread among numerous fields (though most reside in a handful of giant fields) — amounting to about one-fifth of the world’s total. The country exports more oil than any other and exerts an undeniably prominent influence on the world oil market from its seat in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

With a resumé like that and three-quarters of a century of oil-rich history to recall, it is almost unfathomable that Saudi Arabia was once considered a risky proposition for oil companies seeking new sources of crude. That perception began to change after the first commercially viable well was drilled there in 1938. But when two geologists — Robert Miller and Schuyler Henry — employed by Standard Oil of California (Socal) arrived in the Saudi Arabian port town of Jubail on Sept. 23, 1933, the vast expanse of the Arabian Desert that lay before them was still very much an unknown prospect.

An oil well in the Baba Gurgur field in northern Iraq gushes circa 1932. The 1927 discovery of Baba Gurgur helped renew interest among international oil companies that the Middle East might harbor more oil than previously expected. Credit: Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

The British, who had been actively seeking oil abroad since before World War I and who had benefited mightily against Germany by converting their naval ships to burn oil instead of coal (at the behest of then-First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill), were the first to test the sands of the Middle East. Along with a partner company, Burmah Oil, British millionaire William Knox D’Arcy — who had signed a concession agreement with Shah Muzzufar al-Din Kajar in 1901 allowing him to explore part of western Persia (present-day Iran) — struck oil in 1908 at Masjid-i-Sulaiman in the Zagros Mountains.

Despite the promise of this early find, and the presence of natural oil seeps throughout the region, additional deposits were slow to turn up. The slow speed of new discoveries was attributable to a number of factors, not the least of which was the prevailing opinion among geologists (and hence, many international oil companies) that the Persian Gulf — and especially the Arabian Peninsula — was simply not the place to find oil in any significant quantity. Many of the local rulers were also busy trying to consolidate power in their dominions and were reluctant to allow Westerners to set up camp. Besides, most were more interested in finding sources of fresh water — a far more valuable commodity for them at the time, they thought — than oil.

By the end of World War I, however, it had become clear to many nations that a steady supply of oil was crucial to fuel ongoing and rapid industrialization and to maintain their stature and security on the world stage. Hence, although production at home continued, many American oil companies — along with companies from a handful of other Western nations, including Great Britain, France and the Netherlands — began intensifying their search for additional sources. What commenced was an international race to identify and gain access to promising lands via concessions with local rulers.

Following the discovery of oil in the first commercial well in 1938, the oil industry grew rapidly in Saudi Arabia, as did the infrastructure needed to support it. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Gregory Bergman.

But by the late 1920s, some of the world’s major oil companies had begun reassessing the oil potential in the Middle East, at least in part due to Holmes’ persistent efforts to find money to drill. The 1927 discovery of a large deposit dubbed Baba Gurgur near Kirkuk in northern Iraq by the Turkish Petroleum Company (TPC) — jointly owned by several European oil interests — also helped.

By 1931, Socal (later to become Chevron) — one of the so-called baby Standards to emerge from the 1911 breakup of Standard Oil — had gained a Middle East foothold by wresting control of a concession to explore for oil in Bahrain away from these same European companies. They began drilling in October of that year, and on May 31, 1932, Socal struck oil. “Though only modest in production, the Bahrain discovery was a momentous event, with far wider implications … After all, the tiny island of Bahrain was only 20 miles away from the mainland of the Arabian Peninsula where, to all outward appearances, the geology was exactly the same,” writes Daniel Yergin in his Pulitzer Prize-winning account of the oil industry’s history, “The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power.”

Meanwhile, after Holmes failed to secure backing to drill, Ibn Saud, still more interested in finding water than oil, then solicited help from American plumbing mogul Charles Crane. Crane obliged and in early 1931 assigned a mining engineer, Karl Twitchell, to survey the king’s lands for water. The prospects for precious water, Twitchell reported after a year-long trek through the desert, were negligible. But, like Holmes, he had become convinced that there was oil beneath the sand, specifically in the eastern region of al-Hasa.

The Bahrain find was enough to convince Ibn Saud finally that he should allow more expansive foreign exploration, so he dispatched Twitchell to drum up interest. When Twitchell approached Socal in mid-1932 on the king’s behalf to gauge the company’s interest in pursuing a concession agreement, the company was “delighted and immediately receptive,” Yergin writes. The wheels of negotiation were quickly set in motion.

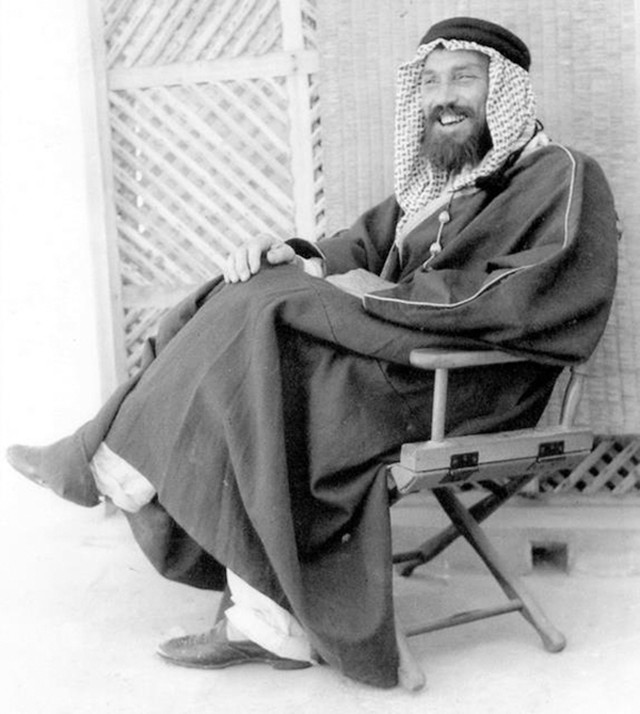

Max Steineke was in charge of Casoc's (California-Arabian Standard Oil Company) operations in the al-Hasa region of Saudi Arabia in 1938. Credit: ©Timothy J. Barger, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0.

In February 1933, Twitchell — now employed by Socal to negotiate on the company’s behalf — returned to Saudi Arabia with a company attorney. They faced only half-hearted competition in their attempt to win the concession, easily besting a bid from the Iraqi Petroleum Company (a rebranding of the TPC). Coming to terms with the Saudi Finance Minister Abdullah Suleiman, who aggressively sought better terms for the king, was more difficult. In early May, though, the two sides reached a compromise and on May 29, 1933, the agreement was signed.

In exchange for a 60-year concession to explore roughly 930,000 square kilometers in al-Hasa, Socal provided payments and loans to the king, the first of which totaled about $175,000, though more were promised down the line and in the event oil was found. (The loans also were only to be repaid from eventual oil royalties if oil was found.)

The company promptly set up its operations in Saudi Arabia, establishing its headquarters in Jeddah and eventually creating a newly formed subsidiary called Casoc (California-Arabian Standard Oil Company), to oversee the concession. Four months later, in September, Robert Miller and Schuyler Henry made the short boat trip from Bahrain to the coastal town of Jubail, ready to begin searching for oil in Saudi Arabia, the first representatives of an American oil company to do so.

The geologists quickly identified a promising site about 100 kilometers down the coast from Jubail. Named the Dammam Dome, it was a jabal (or hill) that they had noted previously from offshore while working in Bahrain. Drilling commenced on the first test well, Dammam No. 1, in June 1934, by which time Casoc’s exploration team had grown to 10 geologists. Despite the geologists’ hopes for early success, the first well failed to produce, as did five successive wells at Dammam.

At the insistence of Max Steineke, appointed chief geologist of the operation in 1936, Casoc continued its efforts, adding more personnel and covering more ground in its search. Steineke also suggested exploring deeper beneath the surface, and in December of that year, Casoc began drilling Dammam No. 7 with that intent. Though beset with technical troubles and equipment problems, Steineke’s intuition that deeper might be better was ultimately validated. Dammam No. 7, drilled more than 600 meters deeper than the earlier test wells, “came in” on March 3, 1938, and was soon producing nearly 4,000 barrels per day.

Oil production in Saudi Arabia took off from there. Renamed the Arabian-American Oil Company (Aramco) in 1943, the company would go on to locate and tap numerous major gas and oilfields in Saudi Arabia in the years to come, including the world’s largest, Ghawar, in 1948. Infrastructure — pipelines, shipping ports and towns, for example — needed to support the industry sprung up as well, bringing rapid modernization with it.

Having already joined forces with the Texas Oil Company (Texaco) in 1936, Aramco brought in Standard Oil of New Jersey (later to become Exxon) and Socony-Vacuum (later to become Mobil) — both baby Standards as well — as partial partners in 1948. Success, of course, brought incredible profit both for Aramco’s partners and for the Saudi leadership.

Aramco’s early partnership with Ibn Saud and its discovery of oil in Saudi Arabia were enormous milestones in 20th century energy exploration and production. As more oil was found, the concession agreement proved malleable, with Aramco repeatedly acceding to Ibn Saud’s push for a greater share of the wealth. In the early 1970s, the Saudi government began acquiring an ownership stake in Aramco, completing a full takeover in 1980 and subsequently renaming the company Saudi Aramco. The nationalization of its oil production operations paved the way for Saudi Arabia to become the influential economic and political player — both regionally and globally — that it is today.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.