by Sara E. Pratt Monday, August 4, 2014

On Sept. 1, 1957, with the stroke of a pen, the U.S. Congress declared Fossil Cycad National Monument in the Black Hills of South Dakota to be no more. At one time, the site held the world’s largest collection of rare fossil cycad-like plants that thrived during the Cretaceous. Over the years, mismanagement, vandalism and theft left the site barren of fossils — the site never had a staff or visitor center, and was never opened to the public. The site’s initial designation as a national monument, in October 1922, had been brought about by the crusading of one man, Yale University paleobotanist George R. Wieland; in the end, he was also responsible for its demise.

Cycads (pronounced sy-ked) are large seed plants with stout, unbranched, woody trunks and a large crown of leaves that look like, but are not closely related to, palm trees. Cycads thrived during the Mesozoic — the Jurassic is sometimes called the “Age of Cycads” — and a few species are still around today.

However, the plants that lived in what is now South Dakota during the Mesozoic were not actually cycads, but cycadeoids. They’re one of the two families in the order bennettitales, which first appeared in the Triassic and became extinct near the end of the Cretaceous. The bennettitales, named for English botanist J.J. Bennett, outwardly resembled cycads, but differed in stem anatomy, stomata type and reproductive structures, with the bennettitales having had flower-like reproductive structures while cycads have cones.

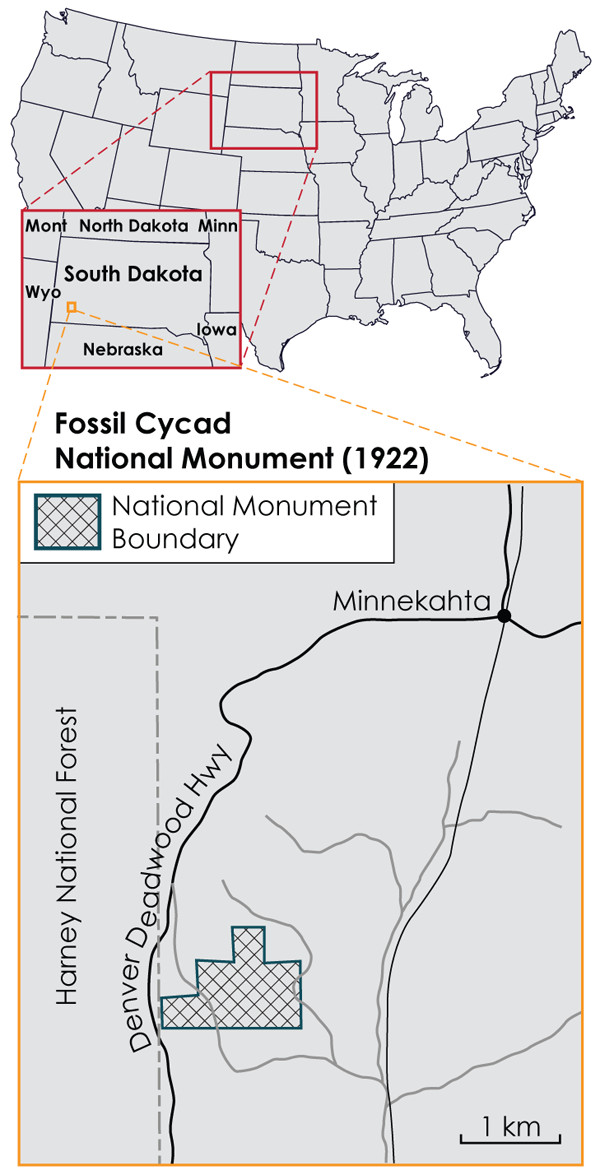

This historical map shows the location of the former Fossil Cycad National Monument in southwest South Dakota, which was dissolved in 1957 after all the visible fossils were removed. Harney National Forest was absorbed into the Black Hills National Forest in 1954 and the name was abandoned. Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI, adapted from a 1922 Department of the Interior map.

“This confusing nomenclature in no way diminishes the scientific importance of these extremely well-preserved plants, which shared the Cretaceous world with dinosaurs,” wrote National Park Service (NPS) paleontologists Vincent Santucci and John Ghist in the May 2014 issue of Dakoterra, the journal of the Museum of Geology at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City.

While cycads are gymnosperms, bennettitales had features similar to those of both gymnosperms and angiosperms, leading some researchers to believe they might have been ancestral to the angiosperms. About 30 species of cycadeoids in two genera have been identified. Fossil specimens, which ranged in height from 1 to 4 meters with half-meter-wide trunks and 3-meter-long leaves, have been found in the U.S., Europe and Russia. According to the records that remain, the fossil trunks rooted in the 120-million-year-old Lakota Sandstone near Minnekahta, S.D., were by far the most abundant and best preserved.

Vague references to areas in the southern Black Hills region that could be the Minnekahta site are found in the records of George Armstrong Custer’s 1874 Black Hills expedition and a U.S. Geological Survey scientific expedition the following year. The first recorded scientific documentation of the site didn’t happen for another 20 years, however.

In 1892, a University of Iowa botany professor, Thomas H. Macbride, who was visiting Hot Springs, S.D., purchased a fossil, specimens of which local ranchers had been collecting and selling to tourists in local curio shops as “petrified pineapples.” MacBride returned to South Dakota in 1893 accompanied by Samuel Calvin, Iowa state geologist and chair of the geology department at the University of Iowa, and with the help of local ranchers, located the Minnekahta site and collected about 40 to 50 specimens. MacBride published the first paper describing the fossil cycadeoids and identifying a new species in an 1893 issue of American Geologist.

That same year, a prospector named F.H. Cole of Hot Springs, S.D., sent photographs of the cycadeoid fossils to paleobotanist Lester F. Ward at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., and later shipped him a specimen. Ward then purchased six more fossils from Cole, four of which represented previously unknown species. Soon, word of the Minnekahta cycadeoids spread in the paleobotany community, and in 1896, Ward was contacted by Yale paleontologist Othniel C. Marsh, who was involved in the infamous Bone Wars of the late 1800s. Marsh was interested in establishing a collection of cycad fossils at Yale, and, over the next few years, Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History acquired 126 cycad trunk fossils from a collector in South Dakota.

Today, the Peabody Museum boasts “the world’s largest assemblage of cycadeoids.” The majority of the museum’s 1,000 specimens, however, were collected by George Reber Wieland, who was studying vertebrate paleontology at Yale when Marsh first sent him to South Dakota in 1898. Wieland would soon shift the focus of his doctoral research to paleobotany and begin a lifelong obsession with cycadeoids. Over the next several decades, Wieland returned to the Minnekahta site regularly, hauling out tons of specimens for shipment back East.

Yet, even as he was plundering the site, he became fixated on preserving it.

Wieland made a career of his research on the cycadeoids of South Dakota, which resulted in the publication of two volumes of the treatise, “American Fossil Cycads,” in 1906 and 1916. In 1920, Wieland applied for and was granted homesteading rights to a 130-hectare plot containing the fossils “in order that the cycads might not fall into unworthy hands.”

Two years later, he offered it back to the federal government to create a national monument, which prompted President Warren G. Harding to seek input from Charles D. Walcott, secretary of the Smithsonian and former director of the U.S. Geological Survey. By now, the site had been stripped of surficial fossils, but Walcott suggested more fossils would later be revealed by erosion, and thus the site was worthy of preservation.

On Oct. 21, 1922, President Harding signed a proclamation under the power of the 1906 Antiquities Act establishing Fossil Cycad National Monument as a unit of the National Park Service.

The administration of the site was assigned to the superintendent of the nearby Wind Cave National Park, but the day-to-day management was entrusted to local ranchers. The first official visit by a National Park Service employee occurred in 1929, when Roger Toll, superintendent at Yellowstone, visited the site and noted in his report that “all available specimens have been picked up, and there is nothing left that is of interest to visitors.”

Toll’s report was filed on Nov. 20, just a few weeks after the infamous “Black Tuesday” stock market crash of 1929. With the ensuing Great Depression, funding was a constant issue in discussions of developing the site, which would require building roads and facilities, including a visitor center.

After Wieland began to press the issue of developing the site in the mid-1930s, he had a series of testy encounters with various geologists and administrators in the park service. This played out through letters and telegrams — in which Wieland sometimes used all capital letters to make his point — and on at least one occasion involved name calling in the press.

In 1935, an excavation headed by Wieland was undertaken to help determine whether the monument justified development. A crew of workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps excavated roughly a ton of new fossil specimens, but they too were removed and stored at Wind Cave National Park, prompting the park service to suggest that a display about Fossil Cycad National Monument be developed there. Wieland vehemently objected and the stalemate continued.

Wieland’s persistence landed him a meeting with Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes in Washington, D.C. But the prevailing attitude within the department at the time was perhaps best epitomized by a July 1937 statement by Undersecretary of the Interior Harry Slattery:

“It is realized that the area is of outstanding paleobotanical interest. But it is also realized that the subject of fossil cycads does not have a broad appeal and, therefore, extensive development of the monument would benefit only a limited group of people. This is particularly true since the area does not possess other outstanding attractions. The scenery is neither impressive nor is it unusual; the geological interest, other than its paleobotanic relations, is not phenomenal; the area is too small for wildlife preservation; the terrain does not lend itself well to recreational development; and there is little historic interest.”

In the years that followed, the soil erosion that Walcott had expected to naturally reveal further specimens never happened. Nevertheless, Wieland continued to fight for the monument’s development — even having Yale architecture students draft designs for a visitor center, which he then submitted to the park service — until his death in 1953.

Four years after the site lost its last champion, it was decommissioned on Sept. 1, 1957. Today, the site falls under the administration of the Bureau of Land Management.

When it was commissioned in 1922, Fossil Cycad National Monument was only the third National Park Service site to preserve fossils. Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona, commissioned in 1906, was the first, and Dinosaur National Monument in Colorado, commissioned in 1915, was the second.

Today, a few other National Park Service sites contain fossil cycadeoids. Due to their rarity, however, there has been occasional discussion through the years of recommissioning the site, but such discussions have foundered on the lack of visible surface fossils.

Instead, Santucci and Ghist have recently undertaken efforts to preserve the legacy of Fossil Cycad National Monument by collecting and curating whatever remnants of the park can be found in NPS archives and collections, including such items as a hand-carved sign warning visitors that “No Prospecting” was allowed. “The story provides a poignant history, which resulted in the loss of not only the fossils at the site but an entire national park,” Santucci says. “Lost, but not forgotten is the legacy we strive for.”

Although the state of South Dakota lobbied for administration of the site to be given to the state, it was ultimately transferred to the Bureau of Land Management. There are currently no further plans to excavate the site in search of any potentially remaining fossils. However, a digital geologic map of the region created by NPS geologist Tim Connors shows other outcroppings of the Lakota Sandstone formation nearby, which, according to Santucci, could yet yield cycadeoid specimens.

It is likely that any remaining fossils will remain entombed at the site, unless uranium or other valuable minerals are found on the land. In 1957, Congress included a caveat in its decommissioning order that hinted at the continued importance of the site: “If any excavations on such lands for the recovery of fissionable material or any other minerals should be undertaken, such fossil remains discovered shall become property of the federal government.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.