by Nate Burgess Tuesday, September 1, 2015

"Colonel" Edwin Drake (right) standing in front of the engine house and derrick of his well at Oil Creek, Pa., circa 1861. Credit: Drake Well Museum.

When Americans think of domestic oil, they likely think of Texas, Alaska or California — vast fields of towering derricks and quietly dipping oil pumps. The American oil industry, however, originated on the other side of the country in the forested wilderness of northwestern Pennsylvania. One of the most pivotal moments in the industry’s early history occurred in October 1865, when Samuel Van Syckel completed more than eight kilometers of underground pipe to transport oil from Pithole, Pa., directly to the railroad. From there, it would go on to Oil City, Pa., and then to major industrial centers, like Pittsburgh.

The story of Van Syckel’s pipeline begins in 1859 at Oil Creek, just south of Titusville, Pa. There, Edwin Drake, working for the newly formed Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company, introduced a novel invention to the American oil industry: an oil well.

Oil was by no means a new discovery in the region. According to Susan Beates, a historian and curator at the Drake Well Museum in Titusville, early French and British explorers gave “Oil Creek” its name because of natural oil seeps located in the region. Native Americans had realized this even earlier and obtained oil from plank-lined pits for centuries — at least as early as A.D. 1410 to 1460, according to radiocarbon dating. “The natives used oil to waterproof items, as a base for paint and for medicine” Beates says. “Though oil is smelly, the dark green liquid does soothe rashes and other ailments.”

In the early 1850s, oil made from coal (the original coal-to-liquids fuel) was used for many purposes. The same companies that used coal oil believed that the crude oil found in Pennsylvania’s natural oil seeps was a similar hydrocarbon and therefore could have similar uses — and similar profits, says Barbara Zolli, director of the Drake Well Museum. Sensing crude oil’s profit potential, a group of chemists, businessmen and lawyers formed Pennsylvania Rock Oil to collect oil from the state’s seeps. The company hired chemist Benjamin Silliman of Yale College in New Haven, Conn., to research the use of seep oil for a variety of industrial purposes, including as an illuminant and a lubricant.

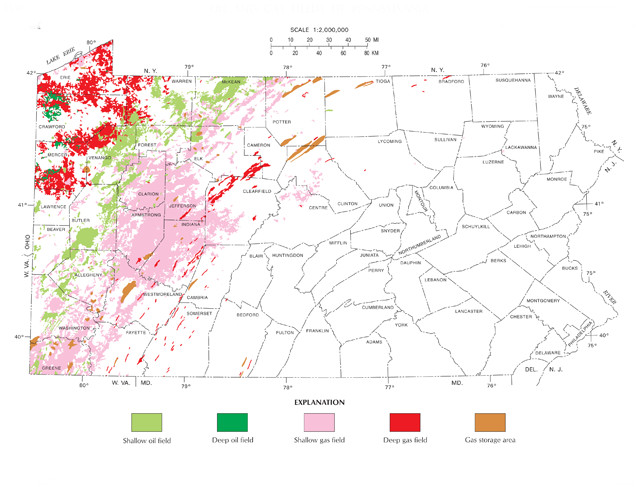

The geology of northwestern Pennsylvania around Titusville and Oil City is notable for its shallow oil fields, shown in light green on this map of state oil and gas resources. Credit: ©K. L. McCoy and Zachary Schmitt, Comm. of Pennsylvania Dept. of Conservation and Natural Resources.

Edwin Drake — an unemployed former rail employee — was hired by thencompany president James Townsend to oversee operations of skimming oil from the Oil Creek seep and explore the possibility of drilling in the area, notes Paul Giddens in his book “Birth of the Oil Industry.” To add some gravitas to Drake’s position, Townsend added the title “Colonel” to Drake’s name, though he had only served in a state militia and had never achieved that rank.

After spending time at the Oil Creek seep, Drake realized that skimming and other less invasive methods of collecting oil at the seep did not yield enough oil to remain profitable. But drilling might work; in fact, wells drilled in southwestern Pennsylvania to obtain saltwater to produce salt often encountered oil leaking into their operations. Drake decided drilling “saltwater” wells in the oil seep would be a better way to recover oil.

Initial drilling efforts went painfully slowly and proved costly, Giddens writes. Many locals scoffed at the idea. In fact, until completion of the well, some referred to Drake’s oil derrick as “Drake’s Yoke” or “Drake’s Folly.” However, once Drake hit oil on Aug. 27, 1859, Drake’s “Folly” proved quite profitable, producing eight to 10 barrels (300 to 400 gallons) of oil a day. Though minute in comparison to how much oil today’s high-tech wells produce, this accomplishment showed the promise of drilling.

A rush to sink oil wells soon began. Virtually overnight, towns sprang up throughout the region, filled with industrious workers ready to tap into the natural resources beneath their feet. Zolli says hundreds arrived within the first year, and thousands more followed in the next several years.

With all of this drilling, oil transportation quickly became a major issue. Railroads did not thoroughly cover the region until 1866, Zolli says, so oil was initially transported from well sites to the railroads and refineries in barrels, using flatboats or wagons. Ida Tarbell, in “History of the Standard Oil Company,” describes how heavy travel over these routes resulted in muddy roads that made travel more and more inefficient. Wagon workers, called teamsters (where the modern Teamsters trade union got its name), realized that oilmen had no other options for transport. Teamsters realized the moneymaking opportunity and therefore charged high, sometimes crippling, prices — as much as $5 per barrel for long distances, Giddens notes. Such high costs were nearly unsustainable for many oilmen, considering the dramatically fluctuating price of crude oil.

Faced with these difficulties, oil companies considered long-distance pipelines. Several refineries already used metal and wooden pipes and troughs on site. However, the cost of establishing longer pipelines and the technical difficulty of maintaining these pipelines deterred companies from investing in such measures throughout the early 1860s. Additionally, teamsters worried about losing their jobs foiled several early pipeline projects by rallying local opposition or even destroying the pipelines.

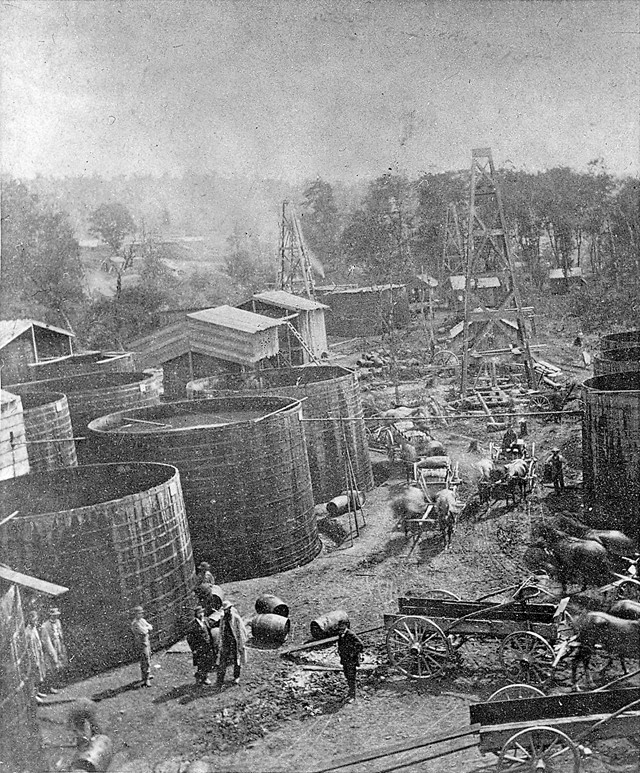

Van Syckel's pipeline transported the oil stored in these large tanks at Pithole well in 1868. At first, teamsters helped transfer oil on site from storage tanks to the pipeline. Later, the pipeline was connected directly to the tanks. Credit: Drake Well Museum.

In 1865, things changed. Van Syckel, working near Pithole, Pa., was faced with an even more difficult commute than other oil drillers. The recently discovered Pithole site was eight kilometers from the nearest railroad station, Miller Farm. Though Pithole quickly became a boomtown, growing to 15,000 people in a matter of months, there was far more oil produced at the site than could be transported over the few rugged roads to the nearest railroad station.

Because of the transport barriers, teamster prices proved unsupportable for the Pithole oil. Van Syckel realized the best solution was to create a pipeline. For his pipeline, Van Syckel laid almost nine kilometers of 5-centimeter-diameter pipe in 4.5-meters-long stretches.

On Oct. 10, 1865, Van Syckel’s pipeline began pumping oil at a rate of 81 barrels per hour to Miller Farm, Giddens writes. This meant about 2,000 barrels of oil arrived at Miller Farm station daily. Previously, this level of transport would have required 300 wagon teams working 10 hours.

Teamsters, realizing that Van Syckel had sidestepped their regional transportation monopoly, attempted several times to vandalize the line. But Van Syckel refused to be bullied; he hired guards to patrol his pipeline and report damage. The pipeline proved so lucrative for Van Syckel that he later added another pipeline parallel to the original. The price of transporting oil ultimately fell to $1 per barrel, Giddens writes.

Once other oilmen observed Van Syckel’s success, they quickly followed suit, building their own oil pipelines throughout Pennsylvania and opening their wells to more efficient oil transport and production. Van Syckel’s pipeline effectively ended the teamsters’ transport monopoly.

Today, northwestern Pennsylvania still pumps oil, but other oilfields in the West and in Alaska produce the vast majority of American oil. Pipelines connecting drilling sites to railways or refineries, however, continue to facilitate oil production in these regions. In this way, Van Syckel and Pennsylvania’s legacy in the oil business lives on.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.