by Sarah Derouin Tuesday, September 19, 2017

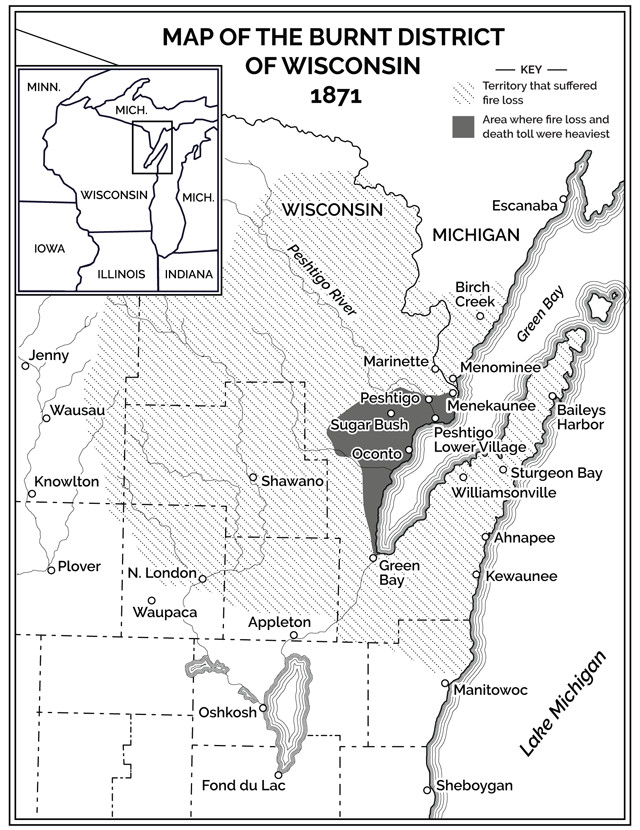

On Oct. 8, 1871, the same day as the Great Chicago Fire, another, even more devastating fire in and around the lumber town of Peshtigo, Wis., burned nearly 500,000 hectares of land and killed as many as 2,500 people — more than any other fire in U.S. history. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI, based on a map from the Atlas of Wisconsin.

On Oct. 8, 1871, the Great Chicago Fire burned through 900 hectares of the city, killing as many as 300 people and leaving another 100,000 homeless. More than 17,400 buildings were destroyed and financial losses totaled more than $200 million at the time (equivalent to $3.7 billion in 2016 dollars).

The ruin brought by the fire to the populous city quickly became national news, bringing the Chicago fire legendary status in local and U.S. history. But that same day, another, even more devastating fire ripped through the Midwest, 400 kilometers north of Chicago around the lumber town of Peshtigo, Wis. The wildfire burned nearly 500,000 hectares of land and killed as many as 2,500 people — more than any other fire in U.S. history. Yet, most Americans have never heard of it.

The Peshtigo and Chicago fires were not the only blazes in the Midwest that week. Fires also broke out in the Michigan towns of Holland and Manistee, prompting some to ask: Were the fires a coincidence, the result of months of dry weather? Or was there something cosmic to blame for all four fires?

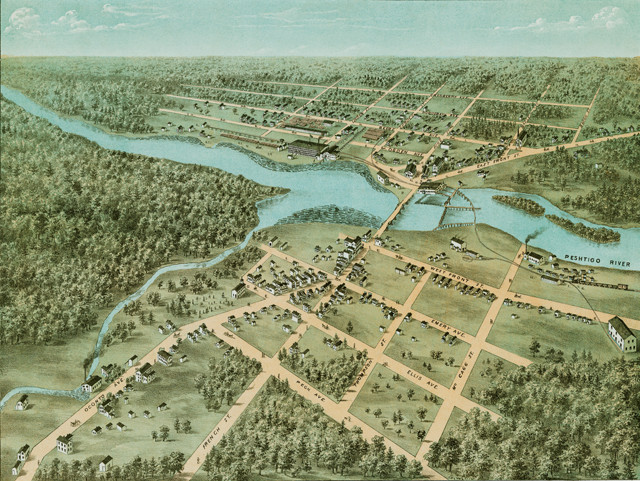

In the 1870s, the upper Midwest, sometimes called the Northwoods, was a boon for the lumber industry. Rapidly growing cities like Chicago and Milwaukee sent lumbermen north to provide timber for building supplies. Rail lines and harbors in Lake Michigan carried wood and manufactured products like shipping boxes to a growing nation. By 1870, the value of lumber produced from Wisconsin forests was valued at $15 million ($277 million today).

A map of Peshtigo, Wis., as it looked in September 1871, the month before the fire. Credit: Wisconsin Historical Society.

The city of Peshtigo is located on the banks of the Peshtigo River, about 11 kilometers inland from Green Bay, an arm of Lake Michigan. The 150-kilometer-long river has plenty of rapids along its length — a plus for transporting large amounts of lumber from the Northwoods downstream to Peshtigo with the river’s current.

During the Quaternary, much of Wisconsin was covered numerous times by the Laurentide Ice Sheet, with the last glacial ice covering the area between about 25,000 and 10,000 years ago — a period referred to as the Wisconsinan Glaciation. When the ice retreated northward, glacial sediment was deposited across the Midwest. This sediment contributed to the creation of productive soils across the region. Northern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan have predominantly acidic, sandy soils; they are classified as spodosols and are a favorite of pine trees. Falling conifer needles combine with water to form organic acids that dissolve iron, aluminum and organic matter in topsoil. White pine trees grow readily in this soil, and the tree was a sought-after commodity that northern Wisconsin provided in bulk.

People flocked to the Midwest for the new jobs the lumber industry provided. In 1870, Peshtigo’s population was about 1,200 people, with an estimated 50 to 100 immigrants arriving by steamer each week, note authors Denise Gess and William Lutz in their 2002 book, “Firestorm at Peshtigo.”

It wasn’t just loggers migrating to the area. Farmers often made their way to the Northwoods to clear a plot of land and make their home. Many prospective farmers headed to a nearby area called Sugar Bush — a series of settlements that took their name from the abundance of sugar maples in the area. Farmers commonly set fires to get rid of trees and stumps so they could clear the fields. “Even the immigrants who came from Belgium, Norway, Sweden, Germany — they knew this is how you clear land. They saw fire as an ally,” Gess said in a 2002 interview with Minnesota Public Radio (MPR).

In the months leading up to the huge October blaze, fires burned constantly, producing so much smoke that residents suffered from smoke-induced symptoms, including lethargy, fevers, hacking coughs and “red eye.”

It was the amalgamation of these smaller fires that would be the undoing of Peshtigo.

During the late 1800s, logging and farming practices created an abundance of slash — piles of felled trees, branches and vegetation cleared from pine forests. Pine needles, small branches and bark covered the ground, creating natural fuel for any fires. The abundance of sawmills also meant a profusion of sawdust, which was spread on streets and flowerbeds, or used as stuffing for mattresses. Additionally, lumber mills and railroads had large quantities of chemicals, glues and paints on hand to make wooden crates, window sashes and furniture.

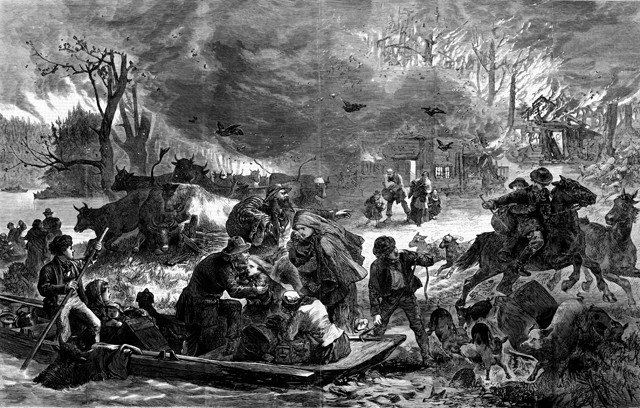

An 1871 Harper's Weekly illustration depicted the horrific scene during the Peshtigo fire as people tried to escape into the river. Credit: Wisconsin Historical Society.

From 1870 to 1871, the Midwest was engulfed in drought. Peshtigo and the surrounding area, which normally gets a meter or two of snow, got almost none that winter. The spring and summer also brought lighter than normal precipitation. Historical records mark the date of the last soaking rain before the fire as July 8, leaving the slash to bake in the dry air for another three months through summer and early fall.

In early October, a cyclonic weather front formed over the Great Plains, creating westerly winds that headed toward Peshtigo. When the storm hit the Northwoods on Oct. 8, a huge temperature difference created strong winds, kicking up coals and fanning the smaller fires, which merged into one enormous fire. A wall of flame nearly 5 kilometers wide and almost a kilometer high roared through the town and quickly spread, according to survivor accounts.

Based on the vitrification of sand, the fire was estimated to have reached more than 1,000 degrees Celsius. It burned so intensely that it created its own weather system, with winds whipping the fire into a tornado-like column of fire and cinders. Authors Gess and Lutz reported that winds rushed through the town at more than 160 kilometers per hour. Escape routes were limited; outrunning the fire was impossible. Many survivors used the same phrase to describe the speed of the flames: “faster than it takes to write these words.”

Some fled to the Peshtigo River, but the cold water created new problems for the residents. Peter Leschak, author of “Ghosts of the Fireground” and a firefighter, said in a 2002 interview with MPR that air temperatures were likely between 260 and 370 degrees Celsius — hot enough to combust hair. People taking refuge in the river had to repeatedly hold their breath and dunk themselves into the cold water, or splash water over their exposed heads. Some who survived the fire died from hypothermia in the river.

The wildfire eventually was quenched by decreased winds and rain the next day. The cold front that brought the strong winds also dropped the temperature, and those who had survived the fire — it is not known how many — were left in danger of succumbing to the elements. All the buildings in Peshtigo had burned to the ground, leaving a flat, smoldering expanse where the town previously stood. The land was burnt deep and the water was fouled — both from the fire and the dead bodies in rivers and wells.

The front page of the Madison Daily Democrat on Oct. 13, 1871, reported "there is scarcely any estimating the damage done to farms and forests, not mentioning the frightful loss of life which has attended the fire." Credit: Wisconsin Historical Society.

After the fire, patches of sand were melted into glass, railroad cars had been tossed off their tracks, and holes dotted the landscape where burned roots turned to ash. The fire destroyed lines of communication out of Peshtigo. The nearest telegraph was in the city of Green Bay, about 70 kilometers to the south at the head of the bay, so the surviving townspeople dispatched a boat to the city to get word to Madison, the state’s capital. As news of the fire was reported in national and international press, donations of tools, bedding, clothing and food poured in from around the world.

No official death toll was determined after the fire. With so many dead and the weekly influx of newcomers, exact numbers were difficult to determine. In 1873, Col. J. H. Leavenworth sent a report to the state government titled “The Dead in the Burned District,” detailing those who were killed in the Peshtigo fire. He compiled a list of those known to have perished and documented what he saw:

“Whole neighborhoods having been swept away without any warning, or leaving any trace, or record to tell the tale … The list [of the dead] can be depended upon as far as it goes, but it is well known that great numbers of people were burned, particularly in the village of Peshtigo, whose names have never been ascertained, and probably never will be, as many of these were transient persons at work in the extensive manufactories, and all fled before the horrible tempest of fire, many of them caught in its terrible embrace with no record of their fate except their charred and blackened bones … for the very sands in the street were vitrified, and metals were melted in localities that seem impossible.”

The landscape around Peshtigo, Wis., after the fire. Credit: Wisconsin Historical Society.

The coincidence of the four separate fires in Chicago, Peshtigo, Holland and Manistee led to speculation about a potential common source for the fires beyond the dry conditions and winds. One hypothesis was raised in 1883 by Ignatius L. Donnelly, a congressman from Minnesota and amateur scientist with an affinity for catastrophism. He published many works on the destruction of past civilizations by floods, comets and meteors, and he proposed that the fires were caused by pieces of Biela’s Comet breaking apart and hitting Earth as meteorites.

The idea was revived in the 1985 book “Mrs. O’Leary’s Comet” by Mel Waskin, the title of which refers to the idea that the Chicago fire was started when Mrs. O’Leary’s cow kicked over a lantern. (Mrs. O’Leary and her cow were exonerated in 1997 by the Chicago City Council.) Another article in 2004 by Robert Wood called “Did Biela’s Comet Cause the Chicago and Midwest Fires?” supported the fire-by-comet theory.

While massive impactors such as the Chicxulub bolide, which hit Earth about 66 million years ago, are thought to have ignited widespread fires due to the tremendous heat and friction produced upon impact, small rocky meteorites are generally poor conductors of heat. NASA debunked that particular ignition method in 2001, noting that there has never been a historically documented case of a small rocky meteorite igniting a fire.

The combination of conditions that caused the Peshtigo fire and others in the Midwest in October 1871 — normal land-clearing methods, extensive drought conditions and a particularly windy weather front — was not unique or even especially rare. Beginning in spring 2016, wildfires ripped through the Fort McMurray area in Alberta, Canada, burning more than 600,000 hectares. “There was a mild winter and not a lot of meltwater from the mountain snowpack,” said Mike Wotton, a research scientist with the Canadian Forest Service, quoted in a 2016 CBC article. “Then there was an early, hot spring, and everything got very dry. Then on top of that, it got windy,” Wotton said.

“This really shows that once a fire like this is up and running, the only things that are going to stop it [are] if the weather changes or if it runs out of fuel to burn up,” said Mike Flannigan, professor of wildland fire science at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, in the same article. “With a fire like this, it’s burning so hot that air drops [of water by firefighters] are like spitting on a campfire.”

Since the late 1800s, major advances have been made in firefighting and public safety that will likely ensure that there will not be another fire as deadly as Peshtigo. But wildfire will continue to be a regular occurrence, Flannigan said in a 2017 Global News interview. “These were not one-offs. It is not a fluke,” he said. “It is going to happen again.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.