by Lucas Joel Tuesday, September 20, 2016

Storm clouds over Leiden, Holland, in 2009. Another storm over the Netherlands, nearly four and a half centuries earlier, helped relieve the city from a Spanish siege. Credit: Daan M, CC BY-SA 2.0.

During the siege of Leiden, Prince William of Orange, leader of the Dutch War of Independence, broke the dikes on the River Maas, allowing the North Sea to flood the countryside to drive the Spanish invaders out. This portrait of him was painted by Adriaen Thomasz Key about five years before the prince was assassinated in 1584. Credit: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Lucas Joel

In 1574, the city of Leiden in the Netherlands was brought to its knees: By August of that year, about 6,000 of the city’s roughly 15,000 inhabitants had either starved to death, been killed by the Black Plague or had succumbed to dysentery. Plague doctors in their crow-beaked masks roamed the streets amid famished and diseased citizens drinking foul water from canals. No one knew when, if ever, help would come, for beyond Leiden’s walls the Spanish army was laying siege and cutting off all supply routes into the city.

Leiden was at the very center of the Eighty Years’ War, also known as the Dutch War of Independence, which had been raging since 1568 between the Spanish Empire and the provinces that today make up the Netherlands. The Dutch were fighting for their independence from Spain, and, in 1574, Leiden was the only thing preventing the Spanish from reaching and sacking two key Dutch cities to the southwest, Delft and The Hague. The whole revolution, it seemed, hinged on Leiden’s survival.

At the time, the revolution’s leader, Prince William of Orange, was elsewhere in Holland trying to raise an army, one that included the pirates and privateers known as the Sea Beggars, to help liberate Leiden. But the Spanish forces, led by Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, the Duke of Alva, were formidable. Orange’s Sea Beggars could not reach Leiden as there were no navigable waterways between them and the city. Desperate, Orange gambled, deciding to break the North Sea dikes and allow the ocean to flood over the land — much of which is at or below sea level — in the hope of washing away the invaders. It was a long shot, but for Orange to repel Alva, and for the revolution to survive, it had to work.

The Eighty Years’ War had religious roots. As part of their Inquisition, the Spanish persecuted Dutch Protestants who did not adhere to Spain’s rigid form of Catholicism. In 1566, there came a tipping point: Dutch protesters, angry at the Inquisition’s harsh policies, defaced and desecrated Catholic churches. In response, King Philip II of Spain sent the Duke of Alva and about 10,000 troops to the Netherlands to restore order. To the Dutch, the troop deployment was an act of war, and in 1568 the 17 Dutch provinces revolted against Spanish rule.

idContainer236">

A 1630 painting by Dirck van Delen depicting iconoclasm, or desecration, in a Catholic church, which helped spark the Eighty Years' War. The Dutch responded to the harsh religious persecution of the Spanish Inquisition by desecrating symbols of Catholicism; here, men stand ready to pull the statue of a saint off its perch, while to the right a statue has been hacked in half. Credit: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

In “The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall,” Jonathan Israel wrote that Alva was “unswerving, even fanatical, in his detestation of Protestant heresy. His reputation was of a man of iron and he was certainly coldly austere and rigidly authoritarian with a streak of harsh irritability in his make-up … He now had his chance to show what severity could do.” To add to his villainous aura, Alva, upon his arrival in the Netherlands, established the “Conseil des Troubles,” to prosecute those involved in heretical activities. By 1569, Israel noted, the council had convicted 8,950 people of treason, heresy or both, and executed about 1,000 of them. For these deeds, the Council of Troubles also became known to the Dutch as the Council of Blood.

" id=""_idContainer238">

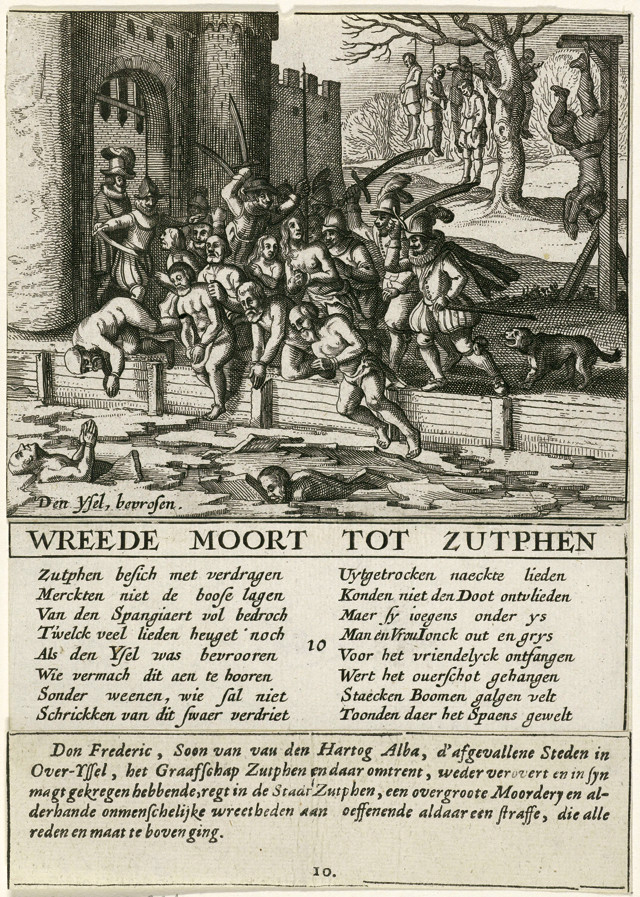

A sketch made between 1618 and 1624 of the mass murder of the citizens of Zutphen as part of the Spanish campaign to quash the Dutch revolt and to extinguish heresy. Here, dissenters are cast into the frozen River Ussel to freeze and drown. Credit: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

A portrait of Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, the Duke of Alva, by Willem Key. Alva led the fight to quash the Dutch revolution for independence. Credit: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Before descending on Leiden, Alva led his troops from town to town, punishing Dutch heretics. At Zutphen, west of Leiden, the Spanish laid siege in 1572. When winter came and the river surrounding the city, the Ussel, froze, Alva’s troops crossed the ice and stormed the streets. On Nov. 14, they massacred hundreds of the town’s roughly 7,500 inhabitants. Many drowned after being pushed through holes in the river’s ice, while others were sent naked out into the winter landscape to freeze to death.

Orange, meanwhile, had fled to Germany. The Council seized his property in the Netherlands and elsewhere, helping provoke Orange to mount his own counterforce. “The Wilhelmus,” the Dutch national anthem, was written in Orange’s honor and from his perspective, and it rings of his feelings during Spain’s war against his people: “Nothing so moves my pity / As seeing through these lands, / Field, village, town and city / Pillaged by roving hands.”

Alva’s march continued, and between 1572 and 1573, his troops besieged the city of Haarlem, northeast of Leiden. In Haarlem, however, about 3,000 rebel troops offered tough resistance to the Spanish. “The besiegers were caught in the bitter cold of winter for many months, suffering heavy losses, as well as incurring huge expense,” Israel wrote. Haarlem resisted, thanks, in part, because Dutch ships could deliver food and supplies to the beleaguered town across Lake Haarlemmermeer. But when the Spanish fleet destroyed the relief ships in May 1573, the city was cut off and soon began to starve. Seven months later, with no alternatives, Haarlem surrendered, and the Spanish army executed more than 2,000 townspeople.

Haarlem’s prolonged siege was not in vain, though: It had given other towns that Alva had not yet reached, like Leiden, time to prepare their own defenses, and had taxed the Spanish troops, who were weary after the long winter. When Alva’s army reached Leiden in October 1573, they chose to cut off and starve out the city rather than attack it outright. Leiden dug in and ordered its citizens to ration food supplies. As time wore on, however, the siege would take its toll on Leiden’s residents, who became increasingly weak. There were calls for the city to surrender to the Spanish, something Orange knew could cripple the revolution.

Orange — who would later become known as William the Silent, an epithet he acquired not because he was reticent, but because he never said what was actually on his mind — was a wealthy nobleman who served the Spanish throne before joining the rebellion, and a deft politician. While a supporter of religious tolerance, he was also “well versed in saying different things to different correspondents, [and] he still professed unswerving loyalty to the Catholic Church in letters to Philip,” Israel wrote.

By the time of the siege of Leiden, Orange had returned to Holland from Germany, and he watched as Spain strangled the city. In March 1574, the siege paused as Alva’s troops turned to face a military force from Germany, led by Orange’s brother, Louis de Nassau. But the Spanish swiftly executed Louis and crushed his forces, returning to Leiden in May to continue the siege. Meanwhile, Orange had been steadily building his own force of about 15,000 men, including the Sea Beggars. But, Israel noted, “the Dutch army was still less than half the size of the [Spanish] king’s and was qualitatively far inferior.” And while Orange had a navy, the Sea Beggars could only reach as far as Noord Aa, a harbor south of Leiden.

Meanwhile, Orange had sent word to Leiden using a homing pigeon, imploring the populace to persist a little longer, for he had a plan: cut the dikes bordering the Maas River and let the North Sea flood the land, which would allow him and the Sea Beggars to attack the Spanish and relieve the city. But when the dikes were cut on Aug. 3, it did not immediately have the desired effect; the water did not rise nearly high enough to drive the Spanish away, or to allow the Sea Beggars to reach Leiden. “Their approach blocked, but within earshot, the relief fleet thundered their guns to bolster the morale of the besieged; but for weeks could advance no further,” Israel wrote. As for Orange, he “had given way to despair, convinced that all was lost.”

A portrait depicting Leiden's mayor, Pieter Adriaansz van der Werf, facing crowds of starving citizens who demanded the city surrender to the Spanish army waiting outside the city gates, which was painted by Mattheus Ignatius van Bree in 1816–17. Van der Werf reportedly told the starving people that they could eat him if they were so hungry, an offer that helped subdue the riled mob. Credit: Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden.

A painting showing the relief of Leiden by the Sea Beggars, who passed out bread and herring upon reaching the city on Oct. 3, 1574, by Otto van Veen. Credit: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

A stew kettle like this was retrieved from the Spanish army's camp at Leiden after they fled the oncoming ocean. Such kettles have become symbols of the siege and its relief. Credit: Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden.

Inside the city, matters grew worse. By now, about 6,000 of Leiden’s residents had died and, on Sept. 8, the town’s desperate citizens began demanding that the city surrender. Seeking to buttress the town’s resolve, Leiden’s mayor, Pieter Adriaansz van der Werf, faced the starving crowd, and reportedly told the people they could eat him if they were so hungry. The rioting crowds subdued, and the siege continued.

Then, on Oct. 1, the sea stirred. Heavy rains fell and strong winds drove seawater overland through the broken dikes. That a storm happened at the right time and in the right place is part luck, but it is also reflective of the climate of the time — a period from the 16th to the 19th centuries known as the Little Ice Age. “The siege coincided with the so-called ‘Grindelwald Fluctuation,’ one of the chilliest periods of the Little Ice Age,” says Dagomar Degroot, an environmental historian at Georgetown University. “Interdisciplinary climate reconstructions suggest that, in the North Sea region, this period was also unusually stormy and rainy.”

Flooded suddenly, the Spanish forces withdrew in such a hurry on the night of Oct. 2 that they left behind many supplies, purportedly even including a pot of stew called “hutspot,” or hodge-podge, which a hungry Leidenaar retrieved and brought back to town. The Sea Beggars reached the city on the morning of Oct. 3 and found the townspeople “so weakened … that scarcely anyone in the town could stand,” according to Israel.

When Orange and the Sea Beggars arrived, they passed out bread and herring to the starved citizenry. To this day, on Oct. 3, Leiden turns festive: people eat bread and herring — as well as hutspot — and dance into the night to commemorate the siege’s end.

Had the storm not arrived when it did and Leiden been lost, Israel wrote, the whole Dutch revolt may have collapsed. Alva, who had once thought he could quash the Dutch revolt in a little under a year, resigned his post. Under his reign, negotiating with the rebels had been out of the question, but Philip permitted Alva’s successor, Don Luis de Requesens, to reconsider: “Talks commenced following the relief of Leiden, which, for the Spaniards, ended any hope of speedy suppression of the revolt.” The Eighty Years’ War did not end at Leiden, however. It was not until 1648 that Spain formally recognized the Netherlands as an independent republic.

Oud West flows by the Museum De Lakenhal, which has a vast collection of art and artifacts telling the story of the city's siege. Credit: Shirley de Jong.

Today, boats amble lazily along the canalways that crisscross Leiden. One canal, Oud West, flows by the Museum De Lakenhal, which has a vast collection of art and artifacts telling the story of the city’s siege. The collection includes letters carried by the homing pigeons from Orange into the city, a painting depicting Leiden’s Mayor van der Werf’s stand-off with his own people, as well as a hodge-podge kettle like the one retrieved after the Spanish army fled. Perhaps the best reminder of the battle, though, is the city itself, which sits precisely at sea level — a fact the Dutch used to turn the tide of war and to alter the course of their country’s history.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.