by Bethany Augliere Friday, September 7, 2018

In the 1830s, in what is now South Africa, the Boers — farmers descended from Dutch settlers who bristled against British rule in the Cape Colony — began trekking farther inland into African tribal territory to find new land. Credit: painting by Charles Davidson Bell, 1898.

The 1886 discovery of gold on a farm in the Witwatersrand region of southern Africa drove the growth of Johannesburg, and gold mining has aided the South African economy for more than a century since. But gold, and diamonds, also fueled the Second Boer War, one of the most destructive armed conflicts in Africa’s history. The war resulted in the deaths of nearly 100,000 people, including tens of thousands of Boer women and children who died in British concentration camps. The consequences of the war, including gold mining’s lasting environmental legacy, and the rise of Afrikaner nationalism that reinforced apartheid, are still felt today.

The Boers were farmers, part of the population of Afrikaners descended from early Dutch settlers who arrived in southern Africa in the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1652, the Dutch East India Company established a colony in what is now Cape Town to control trade routes from Europe around the Cape of Good Hope to India and other eastward destinations. From its beginning, the Cape Colony enslaved indigenous African populations.

In 1806, Britain took control of the Cape Colony during the Napoleonic Wars. The Boers resented Britain’s emerging antislavery policies and the Anglicization that British rule brought to the colony. In the 1830s, the Boers began trekking farther into African tribal territory to find new land, eventually establishing two republics: Transvaal, also called the South African Republic, and the Orange Free State.

For decades, the two new Boer republics lived alongside their British neighbors, albeit with minor fighting amid escalating tensions. The discovery of valuable natural resources escalated these tensions further. Diamonds were discovered in Kimberley near the Vaal River and the Orange Free State border in 1870. In 1877, Britain annexed the South African Republic, but a few years later the colony declared, and won, its independence in a series of skirmishes in 1880 and 1881 collectively known as the First Boer War.

The stage was set for a second conflict, however, when Australian prospector George Harrison discovered gold in the South African Republic. In July 1886, Harrison stumbled upon outcrops of conglomerates featuring rounded pebbles chock-full of gold on the Langlaagte farm outside present-day Johannesburg.

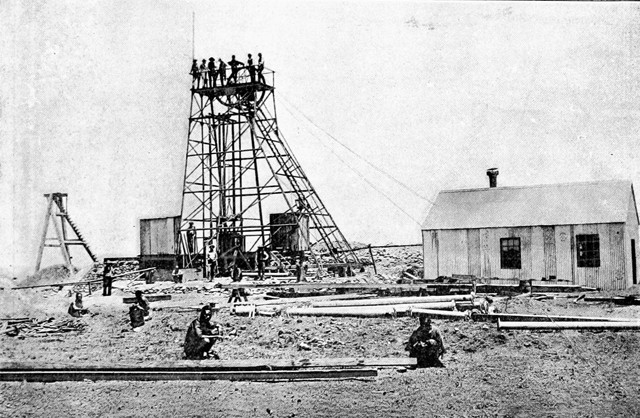

Gold was discovered on the Langlaagte farm in 1886, setting the stage for the Second Boer War from 1899 to 1902. The Langlaagte gold mine is seen here in 1893. Credit: British Library.

In the Gauteng Province of modern-day South Africa, a 56-kilometer-long ridge reaches heights up to 1,700 meters. The ridge’s abundance of cascading waterfalls gave the scarp its name, Witwatersrand, which means “ridge with white waters.” The Witwatersrand Basin stretches in an arc across 350 kilometers between Johannesburg and Welkom and covers an area about the size of West Virginia. Yet, it’s more than just a picturesque geologic formation — Witwatersrand is home to the world’s largest gold deposit.

Whether the mineralization process responsible for the Witwatersrand’s gold deposits involved placer deposits or hydrothermal precipitates, or both, is still debated. Three billion years ago, the basin held a sea, into which flowed rivers carrying sediment eroded from the surrounding greenstone belts, as well as, possibly, placer gold. When the Witwatersrand Sea retreated, the basin continued to fill in with sedimentary and volcanic rock. Eventually, it was buried beneath 23 kilometers of rock; this rock might later have been permeated by hydrothermal fluids from which the gold precipitated.

About 2 billion years ago, a 10- to 15-kilometer-wide meteor landed 110 kilometers southwest of Johannesburg, leaving a crater 300 kilometers across called the Vredefort Dome — the largest verified impact crater on Earth. The Vredefort impact uplifted and tilted the rocks of the Witwatersrand Basin, exposing the gold-containing layers. Were it not for this meteor strike, the gold might have remained undiscovered.

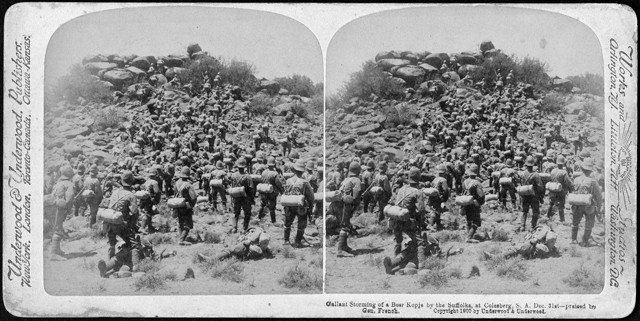

A stereoscopic image of the British Army storming a hill held by Boer forces near Colesberg, South Africa, on Dec. 31, 1900. Credit: Boston Public Library, CC BY 2.0.

With the discovery of gold in Witwatersrand, the South African Republic became the richest nation in southern Africa, posing a threat to British domination of the region. However, the country lacked the resources and manpower to mine and develop the industry.

British migrant workers, called uitlanders, were allowed to enter the country to work the mines, but with limited rights. (The mining also drew many black African workers, who were paid a pittance and granted no rights.)

The British recognized that if uitlanders — who potentially outnumbered the Boers — had full voting rights, they could vote in favor of policies that benefited the British Empire. Britain hoped this would help it wrest control of the South African Republic from the Boers. So in 1897, the British high commissioner, Alfred Milner, demanded that the Boers amend their constitution and give political rights to the uitlanders.

In 1899, the president of the Orange Free State, Martinus Steyn, set up a conference in Bloemfontein to negotiate between the two Boer republics and the British Empire. During the conference, the president of the South African Republic, Paul Kruger, met with Milner, who had three demands: that uitlanders be given the right to vote, that English be used in the South African Republic parliament, called the Volksraad, and that all laws of the Volksraad be approved by the British Parliament.

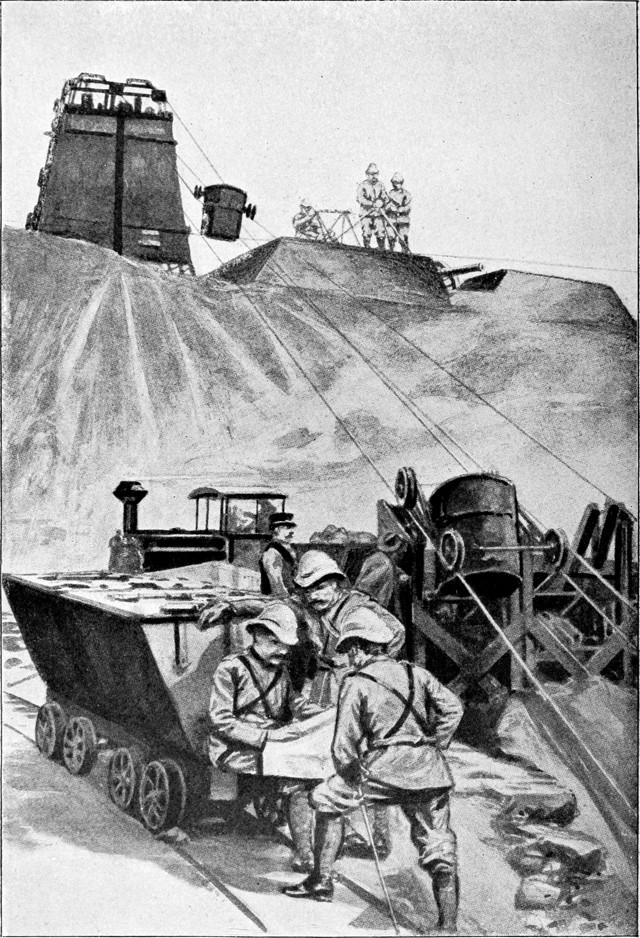

The British Army defends the Kimberley diamond mines in the Cape Colony during the Siege of Kimberley by the Boers, which lasted from October 1899 to February 1900, early in the Second Boer War. Credit: illustration from "War in South Africa," by William Harding, Dominion Co., 1899.

The summit proved a failure, and a major turning point in the events leading toward war. Kruger agreed to reduce the period of time required for uitlander enfranchisement from 14 to seven years, but this was not enough for Milner, who walked out of the conference on June 5.

A few months later, Milner ordered more troops to southern Africa. This alarmed Kruger, who tried to offer concessions, again related to uitlander rights, but Milner rejected them.

Realizing war was likely unavoidable, the Boers took to the offensive. On Oct. 9, 1899, they issued an ultimatum to the British government to remove its troops from the border within 48 hours or they would declare war. Britain did not budge, and the Second Boer War officially began on Oct. 11, 1899.

Late in the war, the Boers used guerrilla tactics, which the British responded to with a scorched-earth policy, burning approximately 30,000 Boer farms and interning civilians. Credit: public domain.

Early in the war, through December 1899, the Boers held the upper hand. Boer armies successfully launched preemptive strikes on three key Cape Colony towns: Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley.

The Boer offensive surprised the British military, which, at that point, was underprepared and outnumbered by the Boers. Though most of the Boer military was made up of civilians, many of them had spent their lives farming and hunting and were skilled marksmen adept at working on horseback.

The war occurred on the lands of various African tribes and where four-fifths of the population was black. While both sides agreed not to arm black Africans, neither upheld this agreement.

n 1900, the British called for reinforcements, which changed the course of the war. This was the largest force that Britain had ever sent overseas, totaling around 180,000 men.

The final and most destructive phase of the war began in late 1900 and lasted until the war ended in May 1902. As the British gained control of both Boer republics, except for a few rural areas, the Boers adopted guerrilla tactics. They raided railways and targeted British bases, attempting to undercut the British Army’s capability to fight.

More than 26,000 Boer women and children died of starvation and disease in British concentration camps during the Second Boer War. Credit: public domain.

In response, the British Army adopted a scorched-earth policy, destroying Boer and African farms to devastate food supplies and shelter. It’s estimated that 30,000 Boer homes and 40 towns were destroyed. The British forces also rounded up Boer women and children and black Africans and held them in concentration camps. More than 26,000 Boer women and children died in these camps from disease and malnutrition. African deaths were not recorded but are estimated to have reached between 13,000 and 20,000.

The Boers surrendered on May 31, 1902, accepting their loss of independence under the conditions of the Treaty of Vereeniging. The two Boer republics became part of the British Empire but were allowed to self-govern beginning in 1906. In May 1910, the two republics became part of the Union of South Africa.

The terms of the Treaty of Vereeniging excluded black Africans from having political rights in the newly organized South Africa. Both the British and Boers worked toward the codification of white minority rule that continued until apartheid was repealed in 1991.

More than a century of gold mining has left a lasting environmental legacy in Johannesburg, South Africa, where piles of mine tailings mark the landscape. Credit: Steven dosRemedios, CC BY-ND 2.0.

The Witwatersrand Ridge runs through Johannesburg, where more than a century of gold mining has left a lasting legacy on the city’s land and water, most notoriously acid mine drainage. According to a 2001 study by the South African Department of Water and Sanitation, gold mining waste was estimated at 221 million tons per year, composing 47 percent of all mineral waste produced in the country and making it the largest single source of waste and pollution.

Holding ponds for mine tailings are filled with toxic heavy metals, including arsenic and lead, and radioactive materials like uranium and thorium, which leach into drinking water and soil. Wind also carries toxic particles from the tailings to nearby towns, posing health risks.

Since 1886, the Witwatersrand Basin has produced more than 40,000 metric tons of gold, estimated to be more than one-third of all gold ever mined on Earth. The impacts of Harrison’s discovery of gold on the Langlaagte farm did not end with the Second Boer War.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.