by Jay R. Thompson Tuesday, July 26, 2016

On Nov. 29, 1991, a dust storm suddenly kicked up along Interstate 5 in the San Joaquin Valley, leaving drivers blinded — from all accounts, visibility was worse than pictured here. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Tom Grundy.

I-5 in the San Joaquin Valley. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Brett Hillyard.

It was about 2:30 p.m. on the day after Thanksgiving and traffic was heavy on Interstate 5, which connects Northern and Southern California. A 31-year-old substitute teacher was traveling southbound on I-5 with her husband, 32, and their two sons, ages 4 and 1. They were a little north of Coalinga, a farming town in the San Joaquin Valley about 250 kilometers south of San Francisco.

The valley, known for its rich farmland, was in a prolonged, years-long drought and had seen almost no rain in nine months. The soil was dry, even for the semi-arid West, so when a massive body of turbulent air blew through, it churned up a wall of dust, and visibility on the highway quickly dropped to almost zero. Vehicles collided, spun out of control and tumbled over; some exploded, sending rocks and car parts flying through the air. More and more vehicles barreled into the blinding dust cloud, not knowing the road ahead was blocked by mounds of twisted metal and burning cars.

Before they knew what had happened, the substitute teacher and her family slammed into a jack-knifed tractor-trailer that blocked several lanes of the interstate, according to Fresno Superior Court documents. The family’s 1980 coupe lodged under the big rig near a diesel tank and was soon engulfed in flames. The young mother suffered “catastrophic burns” as she tried unsuccessfully to save her family from the inferno.

That is but one tragic story among many to emerge from the three-kilometer stretch of I-5 on Nov. 29, 1991, when a blinding dust storm caused 33 separate collisions. Of the 349 people involved in the collisions, 151 were injured and 17 died. About half of the collisions, and all of those resulting in fatalities, occurred in just six minutes between 2:23 and 2:29 p.m. At least 164 vehicles were involved, including 11 tractor-trailers. It was the largest multiple vehicle pileup in U.S. history.

Much of the San Joaquin Valley is farmland, but when drought sets in, that farmland can become very dusty, as it did in 1991. Credit: Erin Partridge, MA, ATR.

The question on everybody’s mind — and in dozens of court cases to follow — was why this pileup happened. Obviously the dust storm instigated it, but was there enough warning to close the highway or warn people? A spokesman for the California Highway Patrol said in a New York Times story two days after the event that the storm arose too quickly for police to take precautions or close the highway.

After investigating the crashes, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) noted that people didn’t all react the same way to reduced visibility; NTSB found the same pattern of behavior with five other incidents as well. Some motorists slow down but others maintain their speed, fearing they’ll be rear-ended if they slow down. But by maintaining their speed, they often end up rear-ending someone else.

Haboobs are large dust storms associated with thunderstorms that often produce very low visibility conditions. The 1991 storm along I-5 was not a haboob, like the one pictured here in Arizona, but it reduced visibility along the roads just like one. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Loretta Hostettler.

Victims and families of victims of the I-5 disaster eventually brought 34 separate lawsuits against various government agencies and corporations. Victims said both the highway patrol and state transportation authority knew of the high winds and dust storm along I-5 “long before the collisions occurred,” according to court documents. More than three years passed before all but one of the suits was settled out of court. The Fresno Bee reported in March 1995 that “state officials never acknowledged any wrongdoing but paid millions of dollars to settle lawsuits filed by accident victims and their survivors.”

Dust storms aren’t uncommon, says Mike Kaplan, a research professor of meteorology at the Desert Research Institute’s Division of Atmospheric Sciences in Reno, Nev. Kaplan and a team of researchers have studied the I-5 dust storm and last summer submitted their latest study of the event to the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. “This planet is loaded with places where dust storms develop,” Kaplan says. Many of these storms occur in mountainous regions with dry climates, with exposed soils and not a lot of vegetation — not unlike much of the I-5 corridor, he says. Some locations, such as the deserts near Phoenix and Tucson, Ariz., experience dust storms frequently, but the I-5 corridor isn’t as prone to dust storms. “This is a fairly isolated event, but it happened to hit a busy interstate on a holiday,” Kaplan says.

San Joaquin Valley farm fields, as viewed from NASA's DC-8 airborne science laboratory. Credit: Jane Peterson/NSERC.

The San Joaquin Valley is dustiest in autumn, but storms thick enough to reduce visibility below 11 kilometers are uncommon, according to a 1995 study of the I-5 dust storm in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. In the 10 years preceding the Nov. 29 dust storm, researchers found no dust-related traffic collisions for that stretch of interstate. But California was very, very dry in 1991, so there was an abundance of dust, Kaplan says.

On average, Coalinga receives 19.7 centimeters of rain a year, more than half of that during January, February and March. April through December usually sees a combined total of 8.6 centimeters of rain, of which only a millimeter or two typically falls in June, July or August. In 1991, however, the only precipitation of note from April through December was a half-centimeter in October.

The study noted that the region had experienced six consecutive years of drought, of which 1991 was the most severe. Many fields along the interstate had been plowed, but remained unplanted because of the severe drought. The lack of vegetation left the dry soil unprotected from wind, and plowing had loosened the soil, making more of it available to be kicked up by winds. The drought, lack of winter rains and introduction of high winds, the researchers wrote, made a dust storm “inevitable.”

The I-5 dust storm was not a haboob — a massive rolling wall of dust associated with a thunderstorm, says Patricia Pauley, lead researcher in the 1995 study and a meteorologist at the Naval Research Laboratory in Monterey, Calif. A haboob results from a strong downdraft that reaches Earth’s surface and spreads out away from its parent thunderstorm, picking up and carrying dust with it. The difference between a haboob and the I-5 dust storm is the source of surface winds.

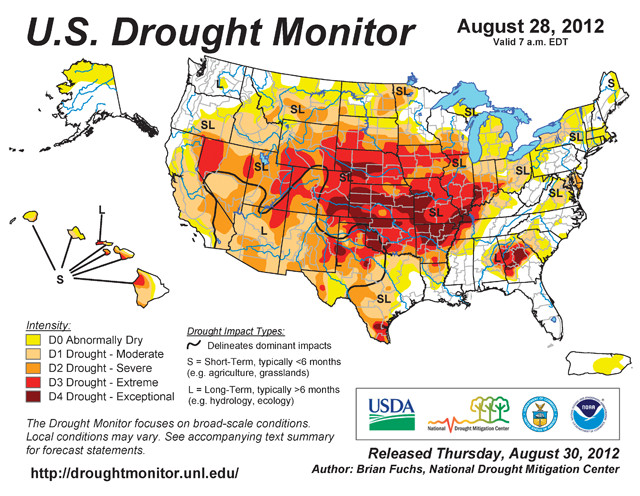

Much of the U.S. was mired in a severe drought this summer, as seen here in this Aug. 28 map. Drought can worsen dust conditions. Credit: National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the USDA and NOAA.

“In the case of the November 1991 dust storm, the high surface winds were related to larger-scale dynamics associated with a strong ‘jet streak’ that was nearly 1,000 kilometers long, 200 kilometers wide, at an altitude of about nine kilometers, and with peak winds of 195 kilometers per hour,” Pauley says. A jet streak is a region of wind embedded in a jet stream that moves faster than the surrounding jet stream. The night before Nov. 29, a jet streak disturbed the atmosphere and caused high-speed winds to descend to an altitude of about three kilometers, Pauley says. When the sun came up Nov. 29 and heated Earth’s surface, warm air rose in some places and descended in others, creating a mixed layer. A typical mixed layer might reach from Earth’s surface to a kilometer in altitude, but Pauley and her colleagues say the mixed layer related to the I-5 dust storm reached as high as two or three kilometers, pulling high-velocity winds down to the surface.

“When that [turbulence] hit the ground, it scoured up the dust,” Kaplan says. The mixing and winds didn’t create one unified dust storm, as with a haboob, Pauley says, but a bunch of smaller, separate dust storms throughout the San Joaquin Valley, Mojave Desert and the Southern California coast. The worst of it lasted two to four hours, with wind speeds reaching 60 to 75 kilometers per hour on I-5, just north of Coalinga. I-5 is an interstate with high speed limits and only a few small towns, Kaplan says. People are driving down the road and “all of a sudden this wall of dust rides right over the highway and nobody can see anything,” Kaplan says.

The California Highway Patrol closed a 160-kilometer stretch of interstate around the accident site for several hours as officers and emergency responders rescued victims and cleaned up the highway.

The cause of the I-5 dust storm may have been unusual, but dust storms continue to threaten the region. In 2011, the Western U.S. was blasted by dust storms. In Arizona, haboobs caused traffic collisions, power outages and flight cancellations. A July storm that hit Tucson that year was reportedly 160 kilometers wide and 1.6 kilometers high with wind gusts that sandblasted the landscape at 112 kilometers per hour. Phoenix was hit three times that summer as well, with one July storm nearly as big as the Tucson storm.

Massive dust storms also struck in 2012, with a July storm in Texas causing a pileup that killed several people. Dust storms in the West may become even more common in the next few decades, researchers suggest. Parts of the West have been in a persistent drought for nearly 10 years. That, combined with grazing cattle, development, removal of vegetation, lack of planting because of the drought, and the use of off-road vehicles can make dust storms more likely or more severe.

Last summer, more than half of the U.S. was in a moderate (or worse) drought, with more than a fifth of the U.S. in extreme drought, according to the National Drought Mitigation Center. As the climate warms, conditions grow worse because drought is all about “accumulated water budgets,” or supply minus demand, says Kelly Redmond, regional climatologist for the Western United States and deputy director of the Western Regional Climate Center, part of the Desert Research Institute. “If temperatures go up, that by itself creates a more negative water budget — greater atmospheric and vegetative demand for water,” Redmond says. Drought may be the new normal, he says.

“During the warm season, all portions of the West are currently projected to receive less precipitation,” Redmond says. However, he adds, “we don’t have very much information or expectation as to what wind extremes and frequency might do.”

In the San Joaquin Valley in particular, the future of dust and its effect on interstate safety is uncertain, but government agencies have taken action to try to prevent events like the I-5 pileup from happening again. When land adjacent to the highway is plowed but unplanted with crops, farmers now plant cover crops to help reduce dust. Automated weather stations with visibility monitors have been installed along the interstate, and when visibility is low, digital message signs are now in place to inform drivers of visibility problems.

Additionally, the California Highway Patrol regularly escorts traffic when visibility is poor. “Whether it be fog, or dust, or smoke from a nearby fire, we’ll lead people out there at a slower pace until that situation clears,” says Sgt. Larkin Vandermel, an officer stationed at the California Highway Patrol’s Coalinga office.

“Anytime it gets windy, if there is a nearby field that has maybe been tilled and it hasn’t been watered, we deal with [dust] from time to time, but it is so sporadic,” Vandermel says. It’s sometimes windy all day with no dust, he says, and then the highway patrol gets a call about dust. Officers guide traffic for 10 minutes to maybe an hour, and then the dust stops. Vandermel suspects there are fewer sources of dust for such severe storms than there used to be. “In 16 years, I’ve watched land be used more and more for agricultural purposes,” he says. “We feed the world here, so there are fewer and fewer places for dust.” These days, low visibility from wildfire smoke is a more common problem, he says.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.