by Patrick Morgan Monday, August 1, 2016

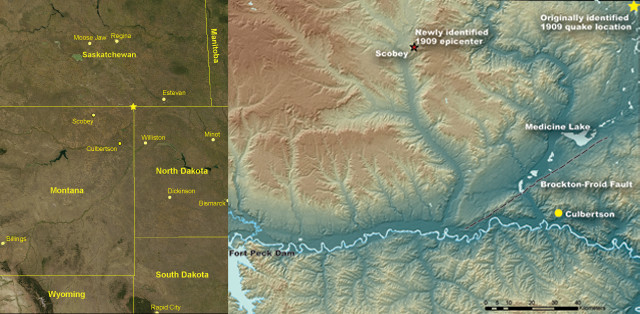

Scientists recently pinpointed the location and size of the 1909 Northern Great Plains earthquake, about 100 kilometers west of where scientists had previously placed the quake's location.Credit: left: AGI/NASA, right:courtesy of Bill Bakun, USGS.

In Culbertson, Mont., at a quarter past nine on a Saturday evening, Ralph Bush and H.G. Walsh were resting in the third-floor apartment of the Reed Cash Grocery when the floor began to rock, vibrating a small penknife right off their table, and sending a candle lamp clattering to the floor. At the nearby Evans Hotel, confusion reigned as the quake shook the two-story brick building, causing frightened guests to flee into the streets. On the second story of the Farmers & Merchants bank, a piano player was entertaining a social gathering at the home of Professor Dale when the shaking sent a vase crashing to the floor. The 15 seconds of quivering was so pronounced at Skelley’s barbershop that, “It rang up a 50-cent cash sale on the cash register, and it has been keeping me guessing how I can balance the darned thing,” Skelley told a reporter from the Culbertson Republican.

Meanwhile, 500 kilometers away in Billings, Mont., S.W. Soule was reading in his home when his door suddenly opened, and he rose to greet a visitor that wasn’t there. Across the U.S.–Canada border, in Estevan, Saskatchewan, the tins and stoves of T.M. Perry’s hardware store clattered against each other, while the Empire Hotel’s chandeliers wobbled. Meanwhile, the night operator at the Canadian Pacific Railroad was working at his desk when his chair suddenly moved backward. “But when he looked behind there was nobody there,” reported the Regina Morning Leader on May 17, 1909.

When it happened, few people thought that this trembling experience was an earthquake, and fewer still recognized its importance as the largest historical earthquake to hit the Northern Great Plains. Some thought a strong gust of wind had vibrated the walls, causing their dishes to rattle. Others, such as I.D. O’Donnell of Billings, Mont., chalked it up to a passing train. Many people didn’t even know an earthquake had occurred until they read about it in the newspaper.

The May 15, 1909, Northern Great Plains earthquake, which technically occurred on May 16 at 4:15 a.m. in Coordinated Universal Time, could be felt across Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wyoming, as well as in the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario and Saskatchewan — an area larger than 1.5 million square kilometers. According to reports at the time, the trembling lasted only 10 seconds in some regions and more than a minute in others, and, although many people walking outside on the streets didn’t feel anything, most everyone inside a building perceived some shaking; the quivering was most pronounced on higher floors. Many people heard a low rumbling like the sound of a passing freight train, whereas others heard nothing.

People felt the Northern Great Plains earthquake in Billings, Mont., but many didn't know it was an earthquake until they read about it in newspapers. Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Overall, the earthquake didn’t cause much damage. In most towns, the trembling buildings caused dishes, bottles and crockery to rattle on the shelves, and tables and beds to shake. “Pictures hanging on the wall were swung out of position,” according to the River Press Weekly, “and dishes and glassware rang in faint alarm as the quake jingled them together.” The Daily Yellowstone Journal reported that, “In some houses, furniture moved around like in a spiritual scene,” and the Harlowton News wrote that, “Water in glasses could be seen to tremble, and electric light globes were set swinging.”

For a century, no one has known exactly how big the quake was. At the time, geologists didn’t have sufficient seismograph technology to accurately measure the earthquake’s magnitude. And the one seismograph in North America that researchers know recorded the 1909 earthquake — in Ottawa, Canada — couldn’t, by itself, indicate whether the quake occurred in Canada or the United States. Geologists estimated a range of likely magnitudes from 5.5 to 6.0, and some placed the magnitude as high as 6.5.

New research suggests a higher seismic hazard along the Brockton-Froid Fault (fault scarps shown here) in northern Montana and into Saskatchewan. Credit: Jon Reiten.

No one knows the exact location of the earthquake’s epicenter either. Because U.S. and Canadian seismologists couldn’t agree on an exact epicenter, in 1978, they decided to arbitrarily stick the epicenter where Montana, North Dakota and Saskatchewan meet. “The epicenter has been recorded in the U.S. and Canadian catalogs for decades at this arbitrary point,” says Bill Bakun, a seismologist at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Menlo Park, Calif.

But this past year, Bakun and two fellow researchers reopened this cold case, and in the process better defined the 1909 earthquake’s intensity magnitude and discovered the quake’s location. These new findings, published in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, mean that engineers may have to reconsider the seismic hazards of eastern Montana, including the strength of a dam that suddenly sits near the fault now known to have caused the Northern Great Plains’ largest quake.

Bakun and his colleagues started by scouring and compiling newspaper reports about the 1909 earthquake, underlining any statements that recorded what specifically happened during the quake — whether dishes rattled or fell off the shelves, the degree of damage, and the extent to which towns experienced the shaking. Based on these data, the team assigned intensities for 90 towns across the Northern Great Plains, nearly double the number of data points previously compiled.

The new placement of the 1909 earthquake epicenter indicates that the Fort Peck Dam might be at higher risk than previously thought. Credit: Harry Weddington, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The traditional method of pinpointing an earthquake using the observations of those who experienced it is to draw contour lines connecting areas of similar intensity, creating what’s called an isoseismal map. In many cases, the lines form rings, and the epicenter lies at the center of the bull’s-eye. “But in our data field,” Bakun says, “you can see large intensity sites superimposed by smaller intensity sites pretty much everywhere,” which means that his team couldn’t use the traditional isoseismal method.

Instead, the researchers used a method Bakun created in 1997 in which he treats each intensity observation as an individual data point. Using a rigorous statistical method, he can then use these data points and uncertainty values to estimate the magnitude and location — independent of each other — that best explain the earthquake observations. This method revealed that the earthquake’s epicenter lies near Scobey, Mont., at the northeastern corner of the state — 100 kilometers west of the designated Montana-North Dakota-Saskatchewan epicenter. Agreeing with two European seismic stations that recorded the 1909 earthquake, the team estimated an intensity magnitude of 5.3.

As one mystery was solved, though, another opened up, says Mike Stickney, a seismologist at the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology in Butte, Mont., and co-author of the new study: The five towns closest to the 1909 earthquake’s epicenter made no mention of the earthquake in their town newspapers or, as far as the researchers can tell, in their records. Although the team doesn’t know why these towns are silent on the issue, they speculate that it may be because the towns knew that the Great Northern Railroad planned on building a spur-line through the area. “In that day and age,” Bakun says, “the railroad coming to your town was the ticket to prosperity,” so these towns probably didn’t report the earthquake because they were afraid the reports might scare away the railroad.

The new location of the 1909 earthquake’s epicenter is important because it places the earthquake closer to a series of known faults in Montana. Western Montana is generally considered more seismically active than eastern Montana, but this updated earthquake location means that the Hinsdale Fault in northeastern Montana may extend 300 kilometers northeastward into southern Saskatchewan and may be seismically active over a larger area than researchers previously thought.

More specifically, the researchers suggest that the Hinsdale Fault may be large enough to support a magnitude-7.0 earthquake. This extension of the Hinsdale Fault also means that the Fort Peck Reservoir now lies within a few tens of kilometers of a potentially active fault — a seismic hazard that had previously never been considered, Bakun says. If an earthquake were to strike near the Fort Peck Dam, Stickney says, this 1930s-era dam would be particularly vulnerable because it was hydraulically emplaced, which means that the workers “basically pumped sand and mud out of the gradually filling reservoir up onto the crest of the dam,” and then forced the excess water out of the structure by driving trucks back and forth on it.

Although the researchers have no reason to think that an earthquake near the Fort Peck Dam is likely, “if that dam were to fail,” Stickney says, “it would send a huge amount of water down the Missouri River Basin,” where it could flood the populated areas downriver. The May 15, 1909, earthquake is an important reminder, he adds, that even tectonically stable regions are not immune to a quake.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.