by David B. Williams Friday, April 22, 2016

The original skeleton of the holotype specimen of Diplodocus carnegii, discovered in Wyoming in 1899, has been on display for more than a century at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, where locals have dubbed it "Dippy the Dino." Credit: Scott Robert Anselmo, CC BY-SA 3.0.

As one of the world’s wealthiest philanthropists, Andrew Carnegie had come to expect that people would praise and honor him, but May 12, 1905, would be an unusual day for the Pittsburgh steel magnate. Never before had he been honored for donating a dinosaur. Carnegie’s contribution of a massive plaster model of a Diplodocus — at the time the largest-known animal to have ever trod the planet — to London’s Natural History Museum was part of the Scotsman’s dream to rid the world of war, which he called “the foulest blot upon our civilization.”

Compact, silver-haired, and wearing his traditional black morning coat and bow tie, Carnegie was a healthy 69 years old on that sunny Friday. Four years earlier he had sold his company, the Carnegie Steel Company, to J.P. Morgan for $480 million, or about $14 billion in today’s dollars.

At the age of 13, Scottish-born Andrew Carnegie emigrated with his impoverished family to Pittsburgh, where he worked as a bobbin boy and telegraph messenger before becoming the personal telegraph operator and eventually protégé of a powerful executive of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Credit: Theodore C. Marceau, Library of Congress.

Carnegie had long been a proponent of social Darwinism and, while head of Carnegie Steel, had presided over one of the most violent episodes in U.S. labor history, the Homestead Strike. However, he also thought and wrote about the rights of workers more than any other Gilded-Age industrialist, and he championed philanthropy. Carnegie, who often said “the man who dies rich, dies disgraced,” donated 90 percent of his wealth during his lifetime and established the Carnegie Corporation in New York City to manage, grow and distribute much of the rest, which it continues to do today.

Initially, much of his donated wealth went to start free public libraries. As a poor, immigrant child in Pittsburgh, he had educated himself at a small private library, which opened to local boys on Saturdays. Carnegie believed that not only would libraries help people of all classes educate themselves, but that they would be especially valuable for immigrants trying to learn American values. With his libraries initiative well underway by the early 1900s, Carnegie turned to the driving passion of his later life — world peace — which manifested itself in his $10 million endowment of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

He also sought to promote peace on a more personal level, through contact with world leaders. He believed they would fall under his persuasive powers, just as the rulers of American business had. That was why, on that May day in 1905, he sat in a crowded room with more than 200 guests around the life-sized model of a giant dinosaur skeleton. """"

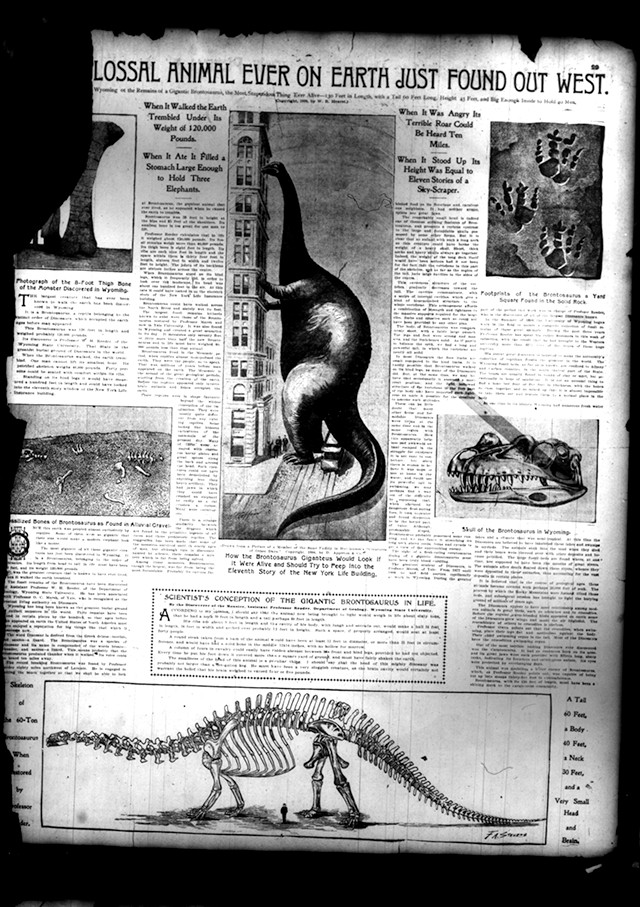

Waiting for the formal ceremony at the museum to begin, Carnegie must have felt that this dinosaur donation was his destiny. Only seven years earlier, while in his New York home, he had turned to page 29 of the Dec. 11, 1898, issue of the New York Journal to find a drawing of an immense dinosaur peering into the 11th story of the New York Life building. Taking up an entire page, the story breathlessly referred to the discovery in Wyoming of a brontosaur with a headline that trumpeted “the most colossal animal ever on Earth.” Its stomach was “large enough to hold three elephants,” its “terrible roar could be heard 10 miles away,” and it produced “thunder when it walked,” or so the unnamed writer claimed.

A story in the Dec. 11, 1898, issue of the New York Journal announcing the discovery of a Brontosaurus in Wyoming included an artist's rendering of the dinosaur with the caption: "How the Brontosaurus giganteus" would look if it were alive and should try to peep into the eleventh story of the New York Life building. Credit: public domain.

As Tom Rea chronicled in “Bone Wars: The Excavation and Celebrity of Andrew Carnegie’s Dinosaur,” Carnegie already knew about this spectacular dinosaur. On Dec. 1, he had seen a short article in the New York Post that mentioned the discovery and had immediately recognized that if he could put the epic monster from Wyoming on display, he would have a huge draw for the museum he was building in Pittsburgh. Ripping out the Post article, Carnegie penned a note to his museum director, William Holland: “My Lord — can’t you buy this for Pittsburgh — try. Wy"ming State University isn’t rich — get an offer — hurry. – AC.”

Taking Carnegie’s words to heart, Holland immediately sent a telegram to William Reed, the man who had found the dinosaur. Reed responded in a letter that the specimen was for sale but hedged on a price. He also noted that the Post’s reporter had made “the usual mistakes of a man not up in science.” In other words, the reporter had exaggerated Reed’s discovery. Holland, however, was persistent — and well funded. He made several trips to Wyoming to see for himself exactly what was in the ground, and hired two of the best fossil hunters away from the American Museum of Natural History to assist him. In early July 1899, Holland’s team rendered Carnegie’s hurriedly penned directive about purchasing Reed’s skeleton moot when they discovered “one of the largest and possibly the most perfect skeleton hitherto found,” as Holland described it in an article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch. Two years later, paleontologist John Bell Hatcher honored the man who had provided the funding by officially naming the animal Diplodocus carnegii.

The original discovery — found in the upper 10 meters of 152-million-year-old calcareous mudstone in the Morrison Formation about 30 kilometers north of Como Bluff, Wyo. — consisted of two skeletons, one of which was mostly complete. This specimen, a"ong with bones from several other skeletons, were put on display at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, where they remain today. Over the years, Dippy the Dino, as it became known, became something of a local mascot; today, it even has its own Facebook page and Twitter feed.

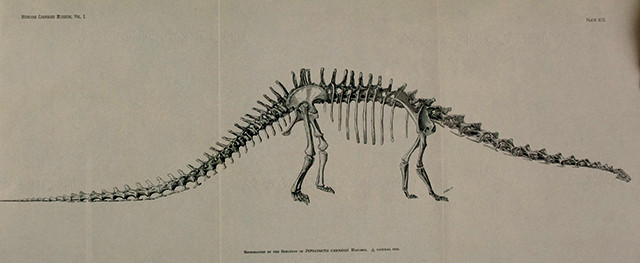

The Diplodocus pleased Carnegie immensely, so much so that he mounted a drawing of the dinosaur from Hatcher’s scientific report on a wall at his castle in Skibo, Scotland. It was here, in 1902, that he began his foray into dinosaur diplomacy. Carnegie hosted a lunch for King Edward VII, during which the British monarch noted the Diplodocus drawing on the wall and asked whether it might be possible to have such a beast in England. (According to a later magazine article by Holland, the king supposedly said, “Oh, I say, Carnegie, we must have one of these in the British Museum.”)

Of course he could obtain a Diplodocus, Carnegie told the king. What an ideal way to further their relationship! Holland, however, knew that finding another nearly complete Diplodocus skeleton was unlikely, so he suggested to Carnegie that he might placate the king by offering a plaster copy based on the bones from Wyoming. With Carnegie’s money, a team of four preparators spent 18 months making the cast, which was shipped to London in 1905.

The May 12 debut of the Diplodocus in London was the social event of the season. A photograph of the event shows attendees dressed to the hilt: The men in attendance wore morning coats and sat with top hats propped on their knees or stood with hats held behind their backs while the women wore wide skirts and elaborate bonnets.

British Museum Director E. Ray Lankester welcomed the distinguished visitors. Corpulent and pugnacious, though a gifted teacher, Lankester began by thanking Carnegie for his kind donation but added, wryly, that the museum’s Hall of Paleontology was “already greatly crowded,” which is why everyone now sat in the Gallery of Reptiles. By the way, noted Lankester, British paleontologists near Oxford had recently excavated a huge dinosaur that rivaled Diplodocus. Dinosaurs, evidently, were a point of national pride.

A sketch from the 1901 report by paleontologist John Bell Hatcher that described and named the first specimen of Diplodocus carnegii, which Carnegie had framed and mounted on a wall at his castle in Scotland. Credit: Hatcher, J.B., Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum, 1:1–63, 1901.

Lankester then turned to the central theme of his talk, that American upstarts, such as the newly rich Carnegie, owed their success to England. “All the great progress that has been made in the American Republic has been founded upon ideas, which have germinated, and inventions, which have been really conceived, in England.” For those in the audience who had missed the symbolism, Lankester explicated that the Diplodocus was merely “an improved and enlarged form of an English creature.” The assembled crowd laughed approvingly.

Carnegie’s turn was next. He said little in regard to Lankester’s crowing. He saw no need. The symbolism was obvious to Carnegie: He, an American, an immigrant from Britain, and one of the world’s wealthiest men, wasn’t donating just any model of any animal, he was donating the greatest animal that ever lived. Carnegie went on to say that the dinosaur had come from “the youngest of our museums on the other side to yours … for all those in America may be justly considered in one sense your offspring; we have followed you.” The meaning was clear: America may owe much to England but, like this dinosaur, it had evolved into something bigger and better than its forebears.

Carnegie focused his speech on his long-term goal of helping create a better world. He had donated the Diplodocus at the behest of the king, a man always ready to “advance the interests of his country … from the peace of nations to the acquisitions of your museum,” he said. He next relayed some of the history of the Diplodocus before returning to his theme of dinosaur diplomacy. In providing this model, he stated that “an alliance for peace seems to have been affected … jointly weaving a new tie, another link binding in closer embrace the mother and the child lands.” After the applause, Carnegie ended by once again mentioning the king’s role in Carnegie’s donation, which he called, “one of the most pleasing acts of my life.”

As Carnegie sat down to hearty applause, he knew that donating his Diplodocus had brought England and America closer together. Soon, he would be using his Diplodocus to try to spread his diplomatic ideals across Europe. By 1909, Carnegie had sent Diplodocus models to museums in Berlin and Paris, followed by Vienna, Bologna, St. Petersburg (that particular model now resides in Moscow) and Madrid. He also provided one for the Museo de la Plata in Buenos Aires. After Carnegie died, his wife sent a model to Mexico City and the Carnegie Museum traded one to Munich. And, finally, in 1957, a concrete model was sent to the Utah Field House Museum in Vernal, Utah, outside of Dinosaur National Monument. All but the Vernal one are still on display, helping to make Carnegie’s Diplodocus arguably the world’s best-known and most-viewed dinosaur.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.