by Lucas Joel Wednesday, February 13, 2019

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers plant trees in Wisconsin in 1937. Across the U.S., the CCC planted more than a billion trees, reclaiming large swaths of forest land that had been logged during the preceding century. Credit: Library of Congress.

On Jan. 25, 1938, a heavy winter snowstorm struck Wisconsin, blocking the road connecting Blackwell to the nearest hospital 10 kilometers away in Laona. The storm left Blackwell resident Stella Simonis, an expectant mother who was hours away from delivering her child, snowed in with no way to get to the hospital, according to an Associated Press article that ran in several Wisconsin papers the next day.

Seemingly out of nowhere, about 80 men showed up with shovels, two snow plows and a tractor, and began clearing a path along the road to Laona. The plows and the tractor were unable to penetrate the drifts, however, so the men used shovels alone to clear the road.

The men were members of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), who lived in a military-style camp in Blackwell. The “boys” of the CCC — so called because most were between the ages of 18 and 25 — had come to the camp out of desperation. The United States was still in the grip of the Great Depression, which had begun in the fall of 1929 with a major stock market crash that crippled the global economy and caused unemployment in the United States to skyrocket to 25 percent.

The CCC, established in 1933, was part of the federal government’s New Deal program, instituted under President Franklin Roosevelt with the broad aim of lifting the U.S. out of its economic despair. The purpose of the CCC, which was first called the Emergency Conservation Work Act, was to help remedy unemployment by putting large numbers of unemployed young men to work improving and maintaining the country’s public spaces.

Between 1933 and 1942, roughly 3.5 million young men went to work on federal projects throughout the United States and its territories. They planted more than a billion trees; fought floods, fires and erosion; and built roads, hiking trails, bridges and more than 800 state parks.

The men who appeared that January night in Blackwell, Wis., had already been working since 1935 to reforest Wisconsin’s logged landscape, large swaths of which, as in many other states, had been clear-cut over the preceding century.

By the time the CCC dissolved in 1942, shortly after the U.S. entered World War II, the CCC boys had planted almost 3 billion trees across the country. “Before Earth Day, there was the CCC,” says Joan Sharpe, president of Civilian Conservation Corps Legacy in Edinburg, Va., which preserves CCC history.

Helping reforest the Wisconsin landscape is what former CCC enrollee Henry “Hank” Sulima did when, at age 18, he enlisted in the CCC and went to serve at a camp in Tomahawk — about 100 kilometers east of Blackwell — from September 1938 to March 1940. Sulima was one of seven children, and, although his father had a job, it did not pay enough to support his entire family. So Sulima joined the CCC and headed from his home in Chicago to the Northwoods of Wisconsin. “Wisconsin seemed so far away,” Sulima says. Each enrollee, he says, received 30 dollars a month for their service — and 25 of those dollars had to be sent directly back to the enrollee’s family.

At Camp Tomahawk, Sulima joined Company 1608 of the CCC. The U.S. military administered the CCC, and the entire program functioned as a kind of peacetime army, Sharpe says. Indeed, the CCC is also sometimes called “Roosevelt’s Tree Army.” Congress passed the legislation creating the CCC in March 1933, and by the end of July of that year about 250,000 American men deployed across the nation, in every state, to camps like those in Blackwell and Tomahawk. The military, Sharpe explains, was the only part of the federal government that was able to mobilize so many people in such a short amount of time.

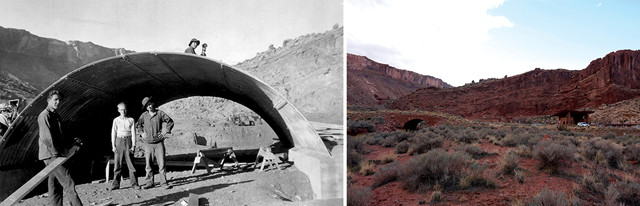

The culvert near the entrance of Arches National Park, under construction by CCC workers in the 1930s (left), is still in use today (right). Credit: left: National Park Service; right: Lucas Joel.

“Throughout the U.S., it is not hard to find locales that were improved through the CCC’s efforts. “The men of the CCC had a huge impact on America that’s little known,” Sharpe says.

In Colorado, near Grand Junction, the CCC boys helped build what would become the 37-kilometer-long Rim Rock Drive that looks out over Colorado National Monument. That road, finished in 1951, winds over thick layers of red-tinted Mesozoic sandstones, the sort of rock that characterizes much of the Desert Southwest’s landscape. Driving along Rim Rock Drive today, it’s still possible to see the structures, including retaining walls and culverts, that the CCC boys created as they built the road.

While some of the organization’s improvements, such as the reforestations and road-building, represented massive efforts, others made smaller but lasting contributions to parks and communities that are still in use today. In Utah, at the entrance to Arches National Park — designated as Arches National Monument from 1929 until 1971 — there is a red sandstone culvert to the left of the entrance road, and, to the right, a sandstone building named “Rock House.” Both were built by the CCC boys. The Rock House was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988 and has served as an administration building for the park and for the Canyonlands Natural History Association.

In Boulder, Colo., in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, a drive up Flagstaff Road — past the site of the old CCC camp — and through Flagstaff Mountain Park’s pine forests will take you past many structures that the CCC created. One of those is the east-facing Sunrise Amphitheater, which looks out over the flat prairie lands that stretch away from the Rockies, and which continues to be a destination for those seeking communion with nature as well as a location for community events and weddings. Across the road from the amphitheater is a CCC-built stone picnic shelter with two fireplaces.

The CCC constructing the Sunrise Amphitheater atop Flagstaff Mountain in Boulder, Colo., in 1933–1934 (top). Today, the gathering place is a popular destination for hikers and a location for community events (bottom). Credit: top: Boulder Historical Society/Museum of Boulder; bottom: Lucas Joel.

“Back in Wisconsin, Sulima helped survey land intended for reforestation. “I, for one, never planted a single tree,” Sulima says. That’s because his job was to figure out, by surveying the landscape, where the rest of the men in his company should plant the trees. For doing this work, Sulima says, he rose through the ranks of the CCC and received “two stripes” on his uniform. These stripes, indicative of the promotion, also meant, in more practical terms, that he received six extra dollars each month. “A two-striper got 36 dollars,” he says. “I was a rich man.”

Often, work at CCC camps was more mundane than the work that produced amphitheaters, forests and other features still standing today. In winter, Sulima says, he would trek out to frozen lakes near Camp Tomahawk. There, he would find parts of the lake surface that had frozen to about 2 feet thick, marking the ice surface into grids. Then, other workers “would come with ice-sawing saws and cut [the ice] into two-foot cubes,” he says.

The company built a stockade and packed all the ice they cut into it. “That was the ice that would hold us over for the next summer,” he says. “And even by the fall there was still some left — that served for cooking, for drinking.”

tionWisconsin_LOC.png” caption=“CCC workers aid the Soil Conservation Service in building terraces to prevent erosion in Vernon County, Wis., in 1939. Credit: Library of Congress.” >}}

“For Sulima, the cooking back at camp was a first — particularly when Thanksgiving and Christmas came around. “I never saw so much food in my life,” he says. “That was the first time I ever tasted turkey.” Besides turkey, he adds, each of the men sitting at the camp’s picnic-style tables received something else during holiday meals that many of them had never seen before: a cigar. “There were 12 cigars on each table,” he says. “We were all smoking, some were vomiting, but we were all smoking cigars,” he says, laughing.

CCC enrollees learned skills that would stay with them for years. Sulima recalls how he and many others took an Army driving course while in Wisconsin. After the U.S. entered World War II, the demand for such skills rose dramatically. “Thousands of those kids went on to be truck drivers in the war,” Sharpe says. “They went on to be truck drivers after the war, and, some of them, that’s all they did the rest of their lives.”

With its military-style administration, the CCC had readied the boys to enlist and go to war. “In many cases, they didn’t even go to boot camp,” Sharpe says. In remarks given in 1980 at The Citadel, the Military College of South Carolina, U.S. Army General Mark Clark — who was deputy commander of the CCC’s Omaha district earlier in his Army career — explained that “to my thinking, the CCC, unrealized by any of us at that time, became the potent factor in enabling us to win WWII.” Clark pointed to workers — cooks, bakers, mechanics, radio operators — who learned their trades in CCC camps, which helped them “groove so easily into the military when they became soldiers.”

aption=“No trace remains of the CCC camp SP-5-C in Boulder, near Flagstaff Mountain Park, but the roads and structures built by the CCC workers continue to enrich communities across the U.S. today. Credit: top: Boulder Historical Society; bottom: Lucas Joel.” >}}

“Sulima, after leaving the CCC, trained as a meteorologist and then joined the U.S. Army Air Forces (the predecessor to the U.S. Air Force). He served for 26 months in the South Pacific as part of the war effort against Japan. His job was to establish weather stations on islands that the U.S. and its allies occupied.

Participating in the CCC, Sulima says, helped lift a whole generation of young Americans like himself out of poverty, instilling in the CCC boys and their families and communities the hope of a better life and future, where before there had been little to none.

The boys received hope, and also gave it. On that snowy night in Wisconsin, in January 1938, the CCC boys of the Blackwell camp were able to clear a path to the hospital for the mother-to-be, Stella Simonis. About 45 minutes after making the arduous journey to the hospital, Simonis gave birth to a son. According to the AP report, “physicians said the boys’ efforts probably saved the lives of mother and son.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.