by Sara E. Pratt Tuesday, February 27, 2018

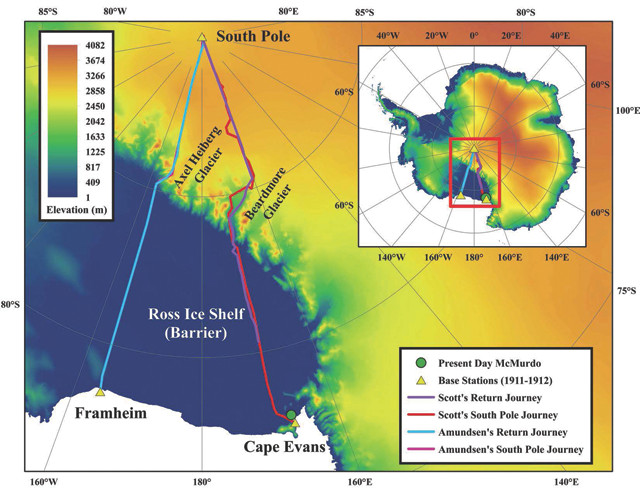

This map shows the routes taken by the teams of Roald Amundsen and Capt. Robert F. Scott from their bases on the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf across the Antarctic Plateau to the South Pole in 1911–1912. Credit: Ryan Fogt/American Meteorological Society/BAMS.

The epic tale of the race between Norway and Britain to be the first to reach the South Pole — and its tragic conclusion with the deaths of British team members in February and March 1912 — is well known. But the details of what happened on the ice, of what went wrong for the British expedition, have continued to be discussed and debated since the bodies of Capt. Robert Falcon Scott and his four crewmates were discovered the following summer. Several recent studies on the Antarctic climate and on the questionable behavior of Scott’s second-in-command are casting new light on the outcome of the expedition.

In the first decade of the 20th century, the heroic age of polar exploration was in full swing. American Robert Peary reported reaching the North Pole in April 1909 (a claim that has since been disputed). And the world now had its eyes trained on the continent at the bottom of the world, which had only been proven to exist in 1820. On Britain’s 1907–1909 Nimrod expedition, Ernest Shackleton and three team members had reached 88 degrees south latitude, the farthest south of any human to date and just 180 kilometers shy of the South Pole.

In the austral summer of 1911–1912, two teams — the Norwegian South Pole expedition led by experienced Arctic explorer Roald Amundsen and the British Terra Nova expedition led by Scott — were poised to make attempts on the South Pole, which, from the coast of West Antarctica, lies more than 1,200 kilometers inland beyond the Trans-Antarctic Mountains. Both teams arrived in Antarctica the previous summer, in January 1911, to allow themselves a year on the continent to adjust to the conditions and prepare for the attempt, including laying depots along the route.

Amundsen’s strategy was for his men, wearing Inuit-style furs instead of wool, to travel quickly on skis with their sledges pulled by large teams of dogs, which could withstand the cold and could be eaten if necessary. The 19-member Norwegian team set up a base camp, called Framheim, in the Bay of Whales near the eastern edge of the Ross Ice Shelf, 1,285 kilometers from the South Pole. A smaller polar party consisting of Amundsen and four others, along with 52 dogs, traveled early in the summer, leaving Framheim on Oct. 20, 1911. They reached the South Pole on Dec. 14, 1911, and returned to base camp on Jan. 25, 1912. On Jan. 30, 1912, the group sailed for Norway.

Scott and his team reached the South Pole on Jan. 17, 1912, the day before this photo was taken. Standing are Dr. Edward Wilson, Scott and Capt. Lawrence Oates. Seated are Henry Bowers and Petty Officer Edgar Evans. All five died on the journey back. Credit: public domain/Henry Bowers.

While Amundsen’s single-minded goal was to reach the pole, Scott intended for his expedition to be one of both exploration and scientific discovery, as had been his 1901–1904 Discovery expedition, the first British Antarctic expedition. Scott’s Terra Nova expedition arrived with a 65-member crew, including a meteorologist, a doctor and a photographer, and they planned to make their attempt on the pole using a combination of dogs, ponies and motor sledges.

The group established a base camp at Cape Evans — named for the expedition’s second-in-command, Lt. Edward “Teddy” Evans — on Ross Island near the western edge of the Ross Ice Shelf, 1,381 kilometers from the pole. Although farther away, it would allow Scott to follow the same route used by Shackleton, whereas Amundsen was charting a new route up the Axel Heiberg Glacier. Because the ponies required warmer conditions than the dogs, Scott and his 15-member support team didn’t leave Cape Evans until Nov. 1, 1911, several weeks after Amundsen’s team departed Framheim. Members of the support team would turn back after caching food, fuel and other supplies at depots along the route, the largest of which was named One Ton Depot.

As the group crossed the Ross Ice Shelf heading inland, they encountered unusually warm weather and a wet snowstorm, which slowed them considerably. They then trekked 240 kilometers up the Beardmore Glacier to reach the Antarctic Plateau and traveled to nearly 88 degrees south, at which point the last support party turned back. Scott intended to choose three men to accompany him to the pole, but at the last minute, he chose four: Henry Bowers, Edgar Evans, Lawrence Oates and Edward Wilson, who would man-haul the sledges from then on. A bitterly disappointed Teddy Evans was left to lead the last support party, with three men instead of four, on its return journey to Cape Evans, during which he fell ill with scurvy.

The daily food ration for a sledge team of four men, including biscuits, tea and pemmican, a mixture of dried meat and animal fat. Historians have suggested Scott underestimated the caloric demands of men hauling sledges across Antarctica. Also, rations previously cached in depots along the return route were missing — the cause of which is explored in a new study. Credit: public domain/Australian National Maritime Museum.

Scott’s polar team continued on, reaching the pole on Jan. 17, 1912, only to find a tent and Norwegian flag left behind by Amundsen. Disappointed and fighting low morale, the team turned around and headed back north. On the return journey, however, the team encountered especially cold conditions — daily low temperatures in late February and early March reached minus 40 degrees Celsius instead of expected lows closer to minus 30 degrees — that slowed them down. The brutal cold was compounded by the team’s increasing weakness, exhaustion and hunger, which grew as they found less food than expected at some depots; at one, an entire day’s biscuit ration for four men was missing.

On Feb. 17, 1912, after sustaining a concussion in a fall at the base of the Beardmore Glacier and suffering from frostbite, Edgar Evans died. On March 16, 1912, Oates, who was suffering from frostbite and exhaustion and feared he was slowing down the others, said “I am just going outside and may be some time,” then stepped outside the tent and was never seen again, Scott wrote in his journal. Finally, on March 29, 1912, after having been trapped by a blizzard for 10 days with only two days’ rations, Bowers, Scott and Wilson died of exposure and starvation, just 18 kilometers short of the One Ton Depot.

The rest of the expedition members overwintered at Cape Evans and then sent out a search party at the beginning of the following summer. They located the bodies of Bowers, Scott and Wilson on Nov. 12, 1912. The British expedition left Anarctica on Jan. 26, 1913, roughly a year after Amundsen left for Norway.

The similar timing yet drastically different outcomes of the expeditions of Scott and Amundsen have invited a century of comparison of the two explorers’ preparation, leadership styles and skills. Everything from their choices of clothing and methods for lashing gear to the sleds, to their means of transportation and navigation, to Scott’s decision to collect rock samples during his trek — 16 kilograms were found alongside his body — has been heavily analyzed. More often than not, history has found Scott lacking.

But with the benefit of a century of hindsight, along with modern-day research tools, scientists and historians are detailing the events that took place at the end of the world that summer with increasing clarity. Recent climate reconstruction studies have found that highly anomalous meteorological conditions — encountered by both teams but at different points on their treks — acted to aid Amundsen and hinder Scott. Additionally, a new analysis of the diaries of Scott and his team, and other archival documents, has revealed that several of Teddy Evans’ actions may have undermined the mission and contributed to the deaths of his five colleagues.

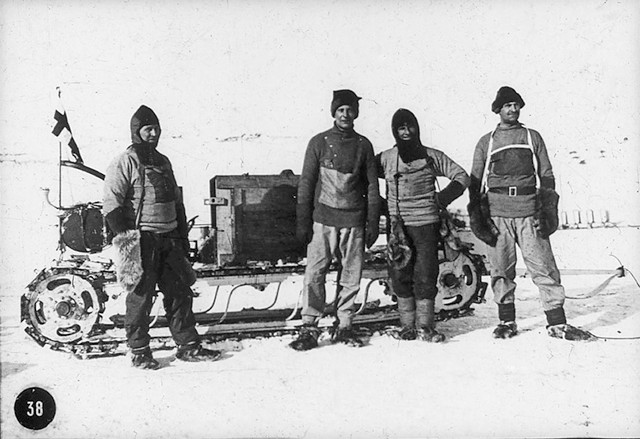

Lt. Edward "Teddy" Evans (second from right), second-in-command of the 1910–1913 British Antarctic expedition, with others in front of a motor sledge. Before leaving England, Evans insisted that Scott remove from the expedition another crew member who had expertise in maintaining the motor sledges, because he outranked Evans. The sledges failed early in the expedition. Credit: public domain/Australian National Maritime Museum.

In an October 2017 study in Geophysical Research Letters, researchers led by Ryan L. Fogt, a polar meteorologist and climatologist at Ohio University, used meteorological observations made regularly in Antarctica since the late 1950s, along with data collected at ground stations and along sledging routes by various expeditions prior to that, to model atmospheric pressures across the continent back to 1905. The researchers found that Antarctica experienced anomalously high pressures — and the warmer temperatures they bring — during many parts of the early and middle 20th century.

That larger-scale study allowed Fogt and other researchers, including Susan Solomon, an atmospheric chemist at MIT, to specifically look at meteorological conditions during the austral summer of 1911–1912 in another October 2017 study, published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. The researchers found that summer was characterized by “exceptional” pressures and temperatures not often reached since.

The warmer temperatures arose while Amundsen’s crew was on the higher and drier Antarctic Plateau, where the conditions allowed the expedition to make good time. Meanwhile, Scott and his team were on the Ross Ice Shelf, where they encountered a blizzard of warm, wet snow that slowed them down.

Solomon previously researched the meteorological conditions of the summer of 1911–1912 and the forecasts of the expedition’s meteorologist George C. Simpson. In her 2001 book, “The Coldest March,” she reported that, in her estimation, Simpson’s forecasts were likely accurate given the resources and tools that he had available and what was known about Antarctic meteorology at the time. The extreme cold that occurred in the latter part of that summer was not only much colder than average, but also persisted far longer than expected, which she concluded was a primary cause of the deaths of Scott and his men.

Other new research suggests that a warmer-than-usual early summer and a colder-than-average late summer weren’t the only surprises that Scott’s team encountered.

In a September 2017 paper in the Polar Record titled “Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?” Chris Turney, a climatologist at the University of New South Wales in Australia, posited that Teddy Evans was to blame for the missing rations, and that Evans also failed to pass on orders from Scott to have a dog-sled team meet the returning polar party on the Ross Ice Shelf. Had the dogs been there, Turney suggested, it would have certainly saved the lives of the team.

urney studied the notes of Lord Curzon, president of the Royal Geographical Society, who, in early 1913, tentatively began an investigation into the circumstances surrounding the deaths. But Evans was not questioned, and the investigation ceased after Evans’ wife died unexpectedly in April 1913. Turney also unearthed original diary entries from various British team members critical of Evans’ behavior, many of which were omitted from published accounts over the years. Beginning early in the expedition, multiple crew members expressed doubts about Evans, and had concerns about him being left in command while Scott was away. Scott himself had written in a letter that he felt Evans was “not at all fitted to be second-in-command,” adding that he planned to “take some steps concerning this.” Why he didn’t is unclear, although it may explain why he did not choose Evans to accompany him to the pole.

Turney also attempted to reconcile the “inexplicable” food shortages Scott’s team found at certain depots. By comparing journal accounts related to food extractions from the depots and the team’s health, he tried to determine when, exactly, Evans fell ill with scurvy on the return trip of the last support party, a date that varied in later published accounts and public retellings.

Weakened by the scurvy, Evans — who had earlier refused to eat the standard rations of seal meat, which was known to prevent scurvy — now required more sustenance, and had to be hauled on the sledge. But journal entries detailing when and how much food was taken from each depot don’t reconcile with what Scott found missing, leading Turney to conclude that extra food was taken before Evans began to show symptoms. The new analysis of the accounts “suggests Evans took the additional pemmican and other supplies when he had not yet succumbed to scurvy, possibly because of his anger at having been sent back early and forced to drag his sledge with just two other men, rather than the expected three,” Turney wrote, adding that the timeline of Evans’ scurvy was likely altered to give “at least some justification for the removal of extra food.”

Upon discovering the bodies of Scott, Bowers and Wilson in November 1912, the search party collapsed the tent over them and built a snow cairn to memorialize the grave. The cairn has since been buried in snow, and continues to move seaward with the advance of the Ross Ice Shelf. Credit: public domain/Australian National Maritime Museum.

The most egregious failure, however, may have been Evans’ disregard of a crucial order from Scott, given on the Antarctic Plateau, to send a dog team out from base camp around March 1 to meet the returning polar party at latitude 82 or 82 degrees 30 minutes, after they descended from the Beardmore Glacier onto the Ross Ice Shelf. Each day, Scott’s team looked for the relief party that never came. On March 10, Scott wrote in his diary: “Shortage on our allowance all round. I don’t know that anyone is to blame but generosity and thoughtfulness have not been abundant. The dogs which would have been our salvation have evidently failed.” Less than three weeks later, they were dead.

“For too long Scott has been held responsible for the death of himself and the men of his party who made the fateful expedition to the South Pole,” Turney said in a statement. “These new documents tell a very different story about how Scott’s planning for the expedition was undermined, reveal that his orders were fatally ignored, and [reveal] why the man who arguably contributed the most to [Scott’s] death was never held accountable for his actions.”

Not many events in history come with the detailed written accounts and weather data like those found in the journals kept by Scott and his men. At the time, the men of the Terra Nova expedition did not know the extent of the larger forces acting against them that summer, and no one man could see the larger picture that was ultimately revealed through historical and scientific analysis — but it had been collectively recorded by them all.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.