by Meg Marquardt Monday, June 20, 2016

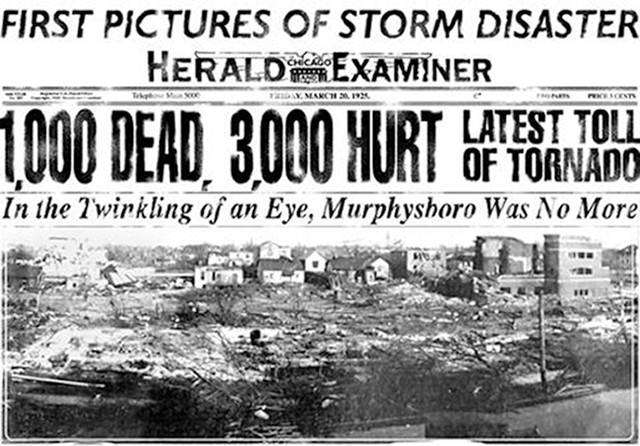

The front page of the Chicago Herald-Examiner, two days after the tornado, shows Murphysboro, Ill., in ruins. The death toll and injuries numbers were incorrect. Credit: Herald-Examiner.

In Murphysboro, 25 people were killed in schools, including the 17 killed in Longfellow, the school pictured here. Credit: NOAA.

On March 18, 1925, the U.S. Weather Bureau’s forecast for the Midwest was not pleasant, but not unusual for early spring: rain and strong, shifting winds. By the end of the day, that simple forecast would prove devastatingly understated. A tornado, or a family of tornadoes, created a path of destruction that stretched from Missouri to Indiana, killing nearly 700 people, destroying 15,000 homes, and forever changing tornado awareness in the country.

In 1925, tornadoes were so poorly understood that even using the word in a forecast was banned by the U.S. Army. According to Gen. William B. Hazen, who dictated the ban in 1887, “the harm done by such a prediction would eventually be greater than that which results from the tornado itself.” So even if the forecasters had recognized the perfect storm brewing over Missouri and Illinois, they would not have been able to put a name to the threat. In the days leading up to the tornado, a lowpressure system was moving through the region. As it moved to the northeast across the Ozarks and into Illinois, the leading cold front was followed by a warm front from the Gulf of Mexico that raised air temperatures significantly in some areas. The warm air added moisture and lift to the region. But to create a wind shear capable of generating a tornado, NOAA scientists today think that there were likely also winds at higher altitudes moving at close to 200 kilometers per hour. Between the stormy weather induced by the front, the warm, rising air from the Gulf, and the strong upper-level winds, the situation was ideal for tornado formation.

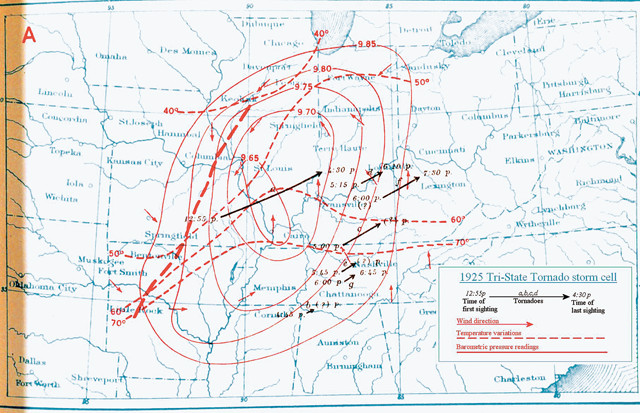

At 1 p.m. on March 18, a tornado formed about five kilometers north-northeast of Ellington, Mo., a town in the southeastern part of the state, killing a farmer. The tornado then began a three-state trajectory, traveling northeast at an average speed of 100 kilometers per hour — a path it would stay on for nearly three and a half hours. It caused substantial property damage in the Missouri towns of Annapolis and Leadanna, damaging $500,000 worth of property.

The tornado next turned its sights on a neighboring county, Bollinger, causing several deaths and multiple injuries. Its impact on schools was particularly deadly. Because the storm formed in the early afternoon, schools were still in session, and with no warning system in place, the storm caught large groups of students and teachers by surprise. In Bollinger, 32 students were injured in two separate schoolhouses. In all, 11 people died in Missouri as a result of the storm.

Weather map tracking the low-pressure system that helped spawn the deadly Tri-State Tornado. The solid black lines show the path of the tornado. The solid red arrows show the wind direction. The dotted red lines show temperature variations and the red circles show barometric pressure readings. Credit: NOAA.

In Illinois, the fatalities were much greater. Over the course of an hour, 613 people died in towns in the path of what was then thought to be a 1.5-kilometer-wide tornado. Murphysboro, Ill., was especially devastated: 234 people died, 25 of whom were in three different schools, and the damage to the town was estimated at $10 million. Two days after the disaster, the headline in Chicago’s Herald-Examiner read: “In the Twinkling of an Eye, Murphysboro Was No More.”

After passing through Illinois, the storm kept on a northeastern track through rural Indiana, where 71 people were killed. The tornado destroyed half of Princeton, Ind., before finally dissipating 16 kilometers outside of town. As cleanup began in the days that followed, the numbers were staggering: The tornado had followed a 352-kilometerlong track, and had killed 695 people, injured an additional 2,027 people, and caused $16.5 million in property damage. It was the deadliest tornado in U.S. history.

When the storm was over, scientists and engineers from around the country arrived to survey the damage, such as boards driven through structures. Credit: NOAA.

However, with all of the destruction, the tornado did produce one positive change: Tornado awareness rose. Storm- and tornado-spotting groups formed, and new technologies — such as radar, which was implemented as a weather tool after World War II — led to a steady decline in storm-related deaths. Communities also learned the signs indicating imminent severe weather. In 1948, after the first successful tornado prediction, weather forecasters were finally allowed to utter the word “tornado.”

Today, about 50 tornado-related deaths occur each year in the United States, down from 500 in the 1920s. Many cities in the Midwest and Ohio River Valley conduct annual Severe Weather Weeks in the spring when tornadoes are most common. These events often include testing the air sirens that signal an impending tornado. They also usually include schools doing their own awareness drills, which often involve either students proceeding to a basement or sheltered, interior room, or students getting under their desks with their hands over their heads.

Thirty-three children were killed in this school in De Soto, Ill. Credit: NOAA.

Despite decades of study, the exact nature of the Tri-State Tornado remains something of a mystery. Debate continues as to whether the event was a single twister or a family of tornadoes. Today, tornadoes that have long paths are usually shown to be multiple funnels caused by an ever-evolving supercell storm. Although the path of a tornado may seem continuous, there are often discreet breaks in the path that a tornado specialist can spot.

Given its record-breaking path length and duration of more than three hours, the Tri-State Tornado should have been multiple tornadoes. But the storm’s path defies that logic. Except for deviations at the beginning and end of the path, the Tri-State Tornado left one continuous line of destruction without a visible break. So at the very least, across the state of Illinois where it did the most damage, the path suggests it was a single massive tornado, the likes of which have not been seen since.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.