by Kate S. Zalzal Tuesday, February 14, 2017

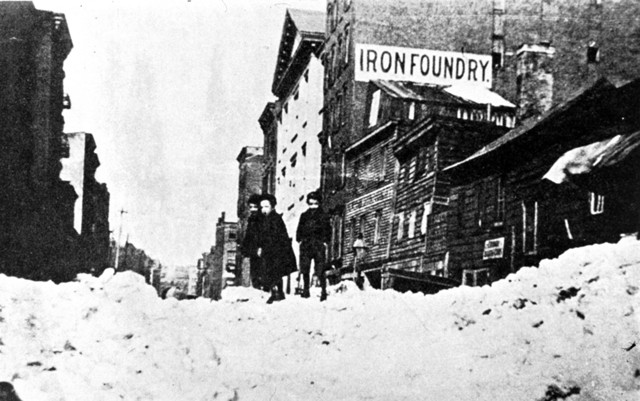

Snow fills the street, sidewalks and doorsteps along a stretch of Park Place in Brooklyn, following the Great Blizzard of 1888. Credit: NOAA.

On Tuesday, March 13, 1888, the streets of New York City were nearly unrecognizable. What had been well-lit homes and storefronts, bustling with shoppers, families, workers and businessmen just two days before, now looked like a frozen battlefield, pummeled by a blizzard whose force had taken the city by surprise. The streets were clogged with deep snow and debris from signs, broken wires, downed poles, trees, and carts that had been abandoned as people fled to shelter. The few people who were out stumbled through deep snow drifts, fighting against a brutal icy wind; some never made it to safety.

During the two and a half days that the Great Blizzard of 1888 raged, it dumped heavy snow and brought hurricane-force winds and frigid temperatures to much of the Northeast, paralyzing cities and towns from the Chesapeake Bay to Montreal, Canada, for up to a week. Snow blocked roads, rail lines and elevated trains. It also took down telegraph and telephone wires in cities, bringing nearly all communication to a halt and leaving residents in disbelief that the conveniences of their modern cities could fail so catastrophically.

Approximately 400 people perished in the storm — including at least 200 in New York City — frozen in snow banks, or killed by fires, accidents or a lack of urgent medical care. It took days to dig out from under the snow, and weeks to restore communication lines and remove the piles of waste and garbage that had built up in the city.

The Great Blizzard of 1888 — also called the Great White Hurricane — remains one of the most famous and severe snowstorms in American history. But it wasn’t just the storm’s meteorological measures that made it so memorable — it brought enormous disruptions to urban life at a time when technology and population growth had surpassed the capacity of city planning to manage it. The storm and its costly aftermath exposed New York City’s weaknesses, but also helped galvanize efforts already underway to modernize communication, transportation and sanitation infrastructure.

Children climb on a snow pile on Baxter Street in New York City. Credit: NOAA.

In the days leading up to the blizzard, temperatures were unseasonably mild. On March 10, a low-pressure system that developed over the central U.S., spanning from Canada to Mexico, began moving east. The front contained two storms, one in the north dropping snow, and one in the south dropping rain. By the evening of March 10, the northern storm began to weaken, while the southern storm appeared to be moving out to sea. But the next day, the southern storm turned and moved northward up the Atlantic coast. The warm, moist storm met with cold northern air, spawning the hurricane-like blizzard.

As the storm moved up the coast, the high winds dashed 35 ships together in Lewes Harbor in Delaware. By the time the storm was over, more than 200 ships had been wrecked or grounded along the coast and at least 100 seamen had died.

By Monday evening, March 12, rain had turned to wind-driven snow in New York City and the temperature fell into the single digits. The storm raged all day on Tuesday. By the time it ended, parts of New Jersey, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts were buried by up to a meter and a half of snow, including more than half a meter in New York City. Wind speeds reached 72 kilometers per hour, producing a lethal windchill and pushing the heavy snowfall into massive drifts, some reaching as high as second-story windows. The high winds also blew down signs, lamps and anything else that was loose in the streets and alleyways. People outside got stuck in the deep snow, abandoning their carts, trucks and even horses when they could no longer move them.

Men stand next to a snow pile after the storm. Credit: NOAA.

Tens of thousands of passengers who had boarded trains on Tuesday morning before realizing the gravity of the storm were caught between railway stations, stuck in freezing, crowded rail cars. Rail lines coated in ice became too slippery, causing commuter trains to derail and collide across New York City. Eventually, passengers abandoned train cars on tracks blocked by deep snow.

A reporter wrote in the New York Sun of his attempts to get to an assignment by elevated train. After nearly six hours of waiting, and only moving a few blocks, he and others on the train climbed down a makeshift ladder to the street. A man who had lashed two ladders together to reach the raised tracks charged each person 25 cents to descend (equivalent to about $6 today).

A horse-drawn trolley car abandoned on 9th Street in New York City. Credit: NOAA.

Perhaps the gravest danger of the storm was posed by the thousands of telegraph, telephone and power poles holding up webs of wires overhead. As the poles and wires crashed down under the force of the wind and the weight of accumulating snow and ice, they took out trees, signs and other poles and lines, leaving twisted, sizzling piles of debris on the snowy streets. Before the storm was over, the city was lit only by gas and candle light.

The falling wires also set off fires around New York City. Firefighters, immobilized like everyone else, could do little to fight the flames in many instances. Property losses were estimated at $25 million (equivalent to about $660 million today).

Men shovel snow into train cars to be taken out of the city. An "Army of the Shovel" was formed to clear the city of snow. Credit: NOAA.

The storm subsided on March 14, but with transportation halted, many New York City residents now faced the immediate crises of running out of food and heating fuel. They also had to contend with the towering snow drifts left behind.

Rail lines and roadways were impassable in the days after the storm, as those assigned to clear the snow were stranded by it as well. Eventually, horse-drawn snowplows cleared the majority of the main streets, but many side streets remained heaped with snow; some piles persisted into the summer. Groups were organized to load snow into railcars and carts to be taken out of the city, or dumped into the sea. When temperatures warmed, the great volumes of melting snow led to flooding in many parts of the city.

Even in the midst of the blizzard, many New Yorkers were incredulous that a storm could materially affect their daily lives. In a tongue-in-cheek response to the dismay that goods were unable to be delivered daily to homes during the blizzard, a March 13, 1888, New York Times editorial read “… it is the small ills of life that worry the most, and probably thousands of New Yorkers yesterday morning … when they had to get through their breakfasts without their favorite newspaper, their hot buttered roll, and their fragrant coffee enriched with boiling milk, began to seriously question whether life was worth living after all, with all those trials and tribulations to undergo.”

A man travels by horse and sleigh during the blizzard. Behind him, telegraph and telephone wires are coated with ice. Credit: NOAA.

In 1888, New York City was the commercial and financial capital of the country, eager to continue staking its claim to a place among the world’s great cities. An influx of wealth and a growing immigrant population created a diverse and cosmopolitan community. Despite the physical destruction and loss of life wrought by the storm, the most troubling aspect for many residents may have been the loss of communication. A New York Times article written in the days after the storm lamented “the ease with which the elements were able to overcome the boasted triumph of civilization … our superior means of intercommunication.”

In the two decades before the storm, New York City’s sky had become crowded with communications and power poles, some up to 30 meters tall and carrying up to 20 wires each. The city had already ordered that wires be buried following public outcry after several gruesome accidents occurred during line repairs. However, the high cost and lack of enforcement meant that most businesses ignored the order. The blizzard reignited the debate, providing visible evidence of the dangers of aboveground lines. According to the New York Times, the storm “may accomplish what months, if not years, of argument might have failed to do.”

It would be several years before the poles finally came down and the city began building its underground communications and electrical system. Alarmed by the paralysis and economic losses brought about by the storm, cities like Boston and New York also began making plans to move public transportation infrastructure underground. Boston began laying subway tracks in 1895, opening the country’s first subway system on Sept. 1, 1897. New York City followed suit in 1904.

The blizzard also exposed the inefficiencies in waste removal in New York City. Piles of garbage, horse manure and sewage filled the streets after the storm. Municipal government officials organized an “Army of the Shovel” to remove snow — only after the snow was gone could the garbage be removed.

Memories of the event remained strong in the years after the Great Blizzard. To the survivors, the storm stood out as an unprecedented natural disaster in the city’s history. The experience also became a source of pride for many, as its destruction propelled progress and technological transformation. Ultimately, the disaster was a great equalizer: Everyone was affected in some way in the struggle to cope with nature.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.