by Brian Fisher Johnson Thursday, January 5, 2012

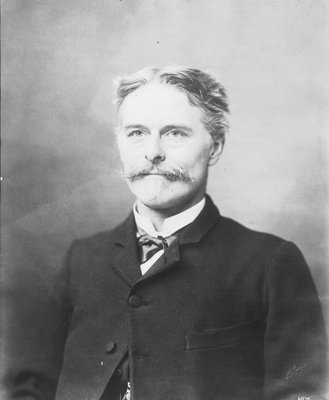

Edward Drinker Cope. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Ewell Sale Stewart Library

Edward Drinker Cope stood before a smoke-filled audience at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, Pa., on March 1, 1872. One of the nation’s leading paleontologists, Cope would present his latest fossil find: an extinct flying reptile he designated Ornithochirus. Certainly the piece would be recognized as a major contribution to the scientific understanding of ancient life. More importantly, Cope thought, he would receive credit as its discoverer.

Cope distributed papers on his lecture sometime after March 12. Little did he know that his archrival, the equally renowned Othniel Charles Marsh, beat him to it — publishing a paper on March 7 in the American Journal of Science and Arts in which he classified the animal under the genus Pterodactylis. Marsh won that round. But it was just the beginning of the “Bone Wars,” a race between Marsh and Cope to discover the most new fossils, during which both paleontologists risked everything from their scientific integrity to their financial well-being to come out on top.

Despite cordial beginnings to their relationship (Cope and Marsh each named species after one another), things quickly grew strained. The gentleman-scientist Cope looked down on Marsh’s lower-class background, while Marsh, a professor at Yale, disdained Cope’s lack of university degrees. Both men could be abrasive and possessive.

Relations soured in 1869, when Marsh pointed out that Cope’s reconstruction of the extinct aquatic reptile Elasmosaurus had the head on the wrong end of the animal. When Cope’s advisor at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia confirmed the error, Cope desperately tried to buy back copies of a paper he had already published on the fossils. Marsh, for his part, ensured that his copies remained available. It was a slight that permanently damaged Marsh and Cope’s relationship.

A battle of pens, pick axes and politics ensued. Cope was more scientifically talented by most accounts, producing paper after paper following numerous field expeditions out West. Marsh was more methodical, careful to note the many errors that resulted from Cope’s furious push for publication.

When not dealing with each other directly, the two battled via their fossil collectors. Hired help reportedly spied on each other and fought in the field. Marsh reportedly even had a site blown up to keep fossils from falling into Cope’s hands. Meanwhile, new dinosaur names entered the literature: Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, Apatosaurus, Triceratops and Ceolophysis.

The feud came to a peak in the 1880s, when Congress began investigating U.S. Geological Survey director John Wesley Powell for profligate spending of funds. As the survey’s chief paleontologist appointed by Powell, Marsh came under doubt as well. But Powell’s convincing explanations to Congress of his fiscal ways left him and Marsh unscathed. Determined to bring Marsh down, however, Cope convinced a journalist to take on his side of the story. “Scientists Wage Bitter Warfare” hit the headlines of the New York Herald in 1890, accusing Marsh of scientific incompetence and plagiarizing his assistants’ work. Marsh skillfully denied the accusations in a follow-up article, effectively clearing his name and re-introducing Cope’s Elasmosaurus gaff from two decades back.

“Most scientists of the day recoiled in horror — and read on with interest, to find that Cope’s feud with Marsh had at last become front-page news,” an observer noted at the time. “Those closest to the scientific fields under discussion … certainly winced, particularly as they found themselves quoted, mentioned or misspelled.” Despite several published responses from Cope, Marsh seemed to have won again.

Eventually, Cope’s battle with Marsh exhausted his inheritance and tried his health. He died from an intestinal illness in 1897, having been forced to sell much of his fossil collection to make ends meet. His will designated that his brain be presented to the Anthropometric Society — likely hoping that scientific size measurements (popular at the time) would prove his superior intellect. Marsh died a distinguished scientist in 1899. In the end, Marsh identified 86 dinosaur species compared to Cope’s 56. Cope, for his part, published five times more papers — not only on dinosaurs, but also on mammals and other animals.

Cope and Marsh collectively increased the number of known dinosaur species dramatically, but their long-standing battle also led to a lot of sloppy science. Perhaps the most famous mishap occurred when Marsh described an Apatosaurus specimen as a new dinosaur, Brontosaurus — a misnomer that has proved as enduring as the paleontologists' actual discoveries.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.