by Megan Sever Thursday, May 15, 2014

Credit: Copyright Shutterstock.com/peresanz.

On June 16, 1963, during the height of the Cold War, Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman to fly in space. It would be 19 years before another woman would fly in space — Soviet Svetlana Savitskaya in 1982 — and 20 years before the first American woman, Sally Ride, made it into space on June 18, 1983. These pioneers inspired the generations of women astronauts who followed. In the three decades since Ride’s foray into outer space, 57 other women have also taken flight (see sidebar) and, last year, half of NASA’s new class of astronauts were women.

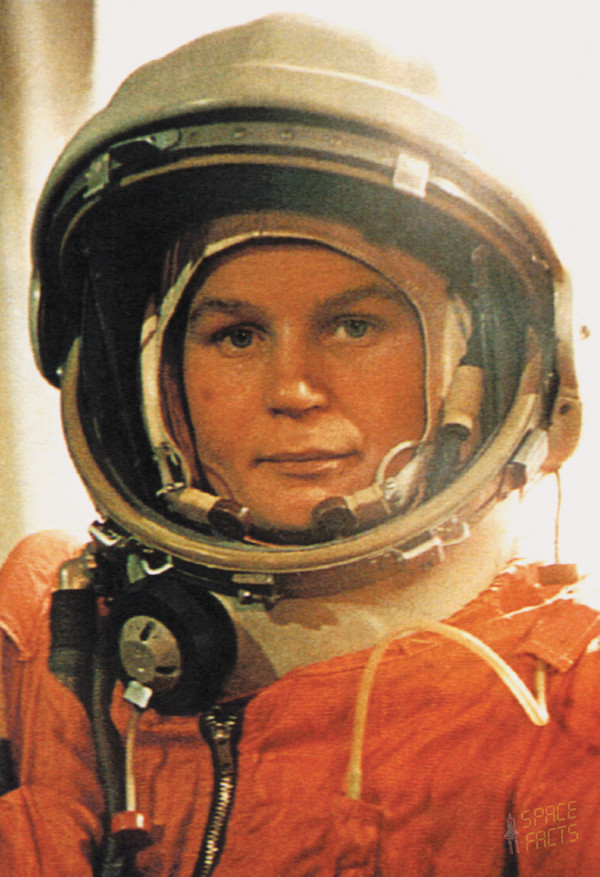

Soviet Valentina Tereshkova was the first woman in space. Credit: ESA.

Valentina Tereshkova was born on March 6, 1937, in the village of Maslennikovo, about 275 kilometers northeast of Moscow. When she was 2 years old, her father went missing and was presumed dead during the Finnish Winter War; her mother worked in a textile plant to support her and her two siblings. Tereshkova attended school from age 8 to 16, after which she joined her mother working on the assembly line and continued her education via correspondence courses.

At age 18, Tereshkova started parachuting. In the meantime, she also joined the Young Communist League and quickly was elected to a leadership role. At age 24, she volunteered for the Soviet cosmonaut program, and her status as an expert amateur parachuter — along with her political activity — ensured her acceptance into the program. Parachuting was important because Soviet Vostok space capsules required the cosmonaut to parachute out prior to landing. She was chosen by Nikita Khrushchev as one of five women cosmonauts, among whom she was the only one to go into space.

After 18 months of training, including tests to see how she held up mentally to long periods of time alone — the Vostok space capsules were single-piloted — and tests to see how her body reacted to zero-gravity conditions, Tereshkova, call sign “Chaika” (“Seagull”), launched into space aboard Vostok 6 on June 16, 1963. She orbited Earth 48 times in 70.8 hours (two days, 22 hours and 48 minutes). In that one flight, she accrued more flight time than all the U.S. astronauts combined had accrued to date, although she never flew in space again.

When she returned to Earth, she was honored with the title, “Hero of the Soviet Union,” and awarded the “Order of Lenin” medal. Over the years, she has also received dozens of other awards, including the United Nations Gold Medal of Peace, which she received after traveling around the world to promote Soviet science.

After her pioneering space flight, Tereshkova went on to earn a doctorate in engineering from the Zhukovsky Air Force Academy; she became a test pilot and instructor for the Soviet space program as well, retiring in 1997. In the meantime, she held multiple national roles: She headed the Soviet Women’s Committee, the International Cultural and Friendship Union and the Russian Association of International Cooperation, and as of last year was still serving as a member of the Russian parliament.

One of her lasting legacies is that her photos of the horizon, taken aboard Vostok 6, were later used by scientists to identify aerosol layers in the atmosphere.

Tereshkova recently told Russian President Vladimir Putin that she would like to fly to Mars, even if that meant a one-way ticket.

Sally Ride was born in Encino, Calif., on May 26, 1951, to a political science professor father and a counselor mother. She was a gifted athlete, and briefly attempted to play professional tennis. After about a year on the professional circuit, she quit tennis, however, and matriculated at Stanford University, where she earned bachelor’s degrees in English and physics, a master’s in physics and eventually a doctorate in physics in 1978. That year, she answered an ad placed by NASA in the college newspaper seeking astronaut candidates — especially engineers and scientists, and, for the first time, women.

Ride was one of six women chosen as 35 astronaut candidates from among 8,000 applicants. She completed one year of training and evaluation, which included parachute training, water survival, navigation, radio communication and training in zero-gravity conditions. In 1981 and 1982, Ride served as capsule communicator for shuttle flights, and on June 18, 1983, she launched into space aboard Challenger.

Ride’s 147-hour mission involved using a robotic arm to deploy and retrieve communications satellites and studying the effects of zero gravity on ant colony behavior. Of the mission, she said: “The thing that I’ll remember most about the flight is that it was fun. In fact, I’m sure it was the most fun I’ll ever have in my life.”

Ride flew into space once more, in 1984, and was scheduled for another mission, which was scrubbed after the ill-fated Challenger disaster in 1986. She served on the presidential commission investigating the Challenger accident, after which she was assigned to NASA headquarters to work on long-range and strategic planning for the space agency.

Ride left NASA in 1989 and joined the University of California at San Diego as a physics professor and director of the California Space Institute. In 2001, she and her long-time partner Tam O’Shaughnessy co-founded Sally Ride Science, an organization devoted to motivating young people — especially girls and women — to pursue careers in science, math and technology. Continuing her passion for education, she wrote or co-wrote seven children’s science books.

Throughout her career, Ride served on numerous boards, from the National Research Council’s space study boards to the NCAA Foundation. She also served on the commission investigating the Columbia shuttle disaster in 2003, making her the only person to serve on commissions investigating both NASA shuttle disasters. Ride was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and the Astronaut Hall of Fame, won the Jefferson Award for Public Service and many other awards, and in 2013, was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. The award was accepted by O’Shaughnessy, after Ride died of pancreatic cancer in 2012.

Ride signs autographs for kids at the 2007 Sally Ride Science Festival at NASA Ames. Credit: NASA Ames/Dominic Hart.

Today, Tereshkova continues to lead by example, working in the Russian parliament, and Ride’s legacy lives on through Sally Ride Science, which O’Shaughnessy continues to lead, providing science programs and publications for upper elementary and middle school students, their parents and teachers.

The first three women in space — Valentina Tereshkova, Svetlana Savitskaya and Sally Ride — broke the barrier for women in space exploration, and to a degree, women in science. Thanks to these pioneers, the young women of Generation X grew up believing they could shoot for the moon, and actually have a chance of getting there.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.